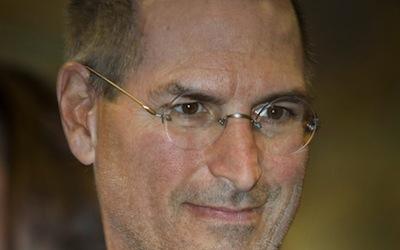

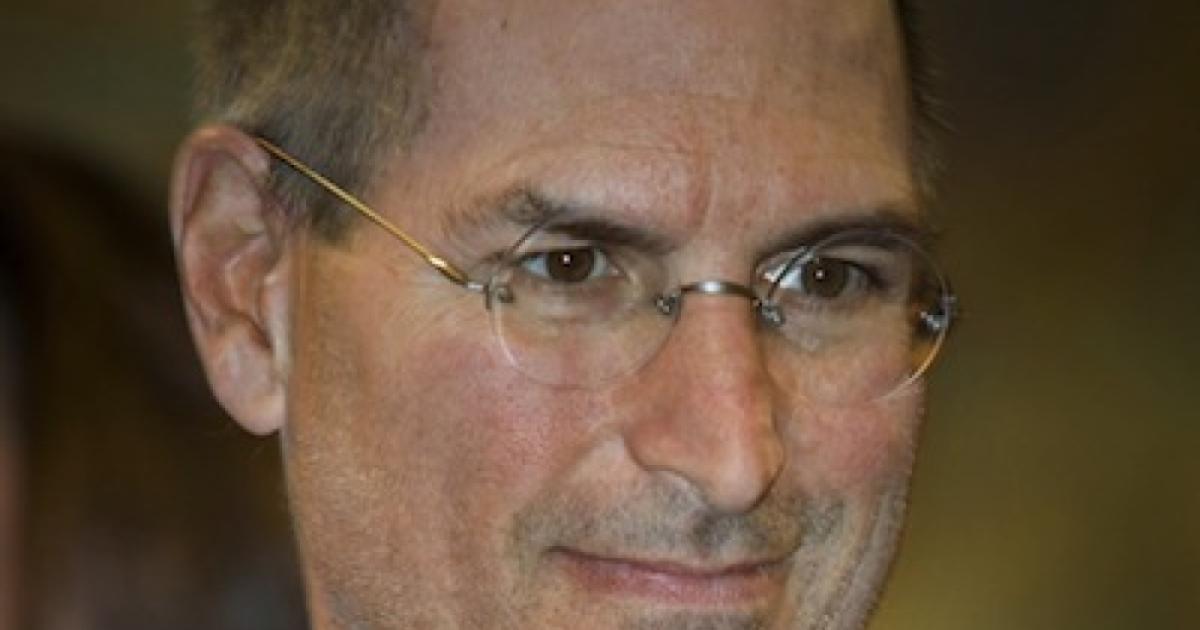

It has been more than a year since Steve Jobs died, and yet, his greatest achievement has eluded most observers. It has not been identified or discussed. Most observers get his basic accomplishments right. For instance, Walter Isaacson, in his official biography of Jobs, writes, “Jobs stands as the ultimate icon of inventiveness, imagination, and sustained innovation. He and his colleagues at Apple were able to think differently: They developed not merely modest product advances based on focus groups, but whole new devices and services that consumers did not yet know they needed.” How true. But there’s more to it than that.

Jobs was not a typical CEO. He took a leading role in many aspects of Apple’s business and didn’t simply delegate. He was concerned with both the big picture and the minutest details. He would boldly and abruptly settle a massive lawsuit with Microsoft or change the very payment structure in the publishing world, and then later pick the specific quarry in Italy and the exact color of tile for the flooring in all Apple stores. He cared deeply about the packaging of Apple’s products. He was as much a detail control freak as he was a big-picture visionary.

You may have heard about how Jobs and the people at Apple spent a fair amount of time and energy making even the insides of Apple’s products beautiful. Many companies do not even devote time to making the outsides of their products beautiful, and here was Jobs “wasting” company money, as some criticized, on something that most people will never see. But Jobs explained that he learned this from his dad, a master craftsman. “He loved doing things right,” Jobs said. “He even cared about the look of the parts you couldn’t see.” Jobs’ behavior does seem curious. After all, who really does see the inside of a computer case?

Our view of Jobs becomes clearer when we realize that Jobs was smitten. Jobs cared because he was in love—not the warm and hand-holding kind of love between two people; rather, Jobs loved “insanely great” technological products. “The first computer terminal I ever saw was when my dad brought me to the [NASA] Ames Center. I fell totally in love with it,” he said. Later, Jobs would observe, “The only way to do great work is to love what you do.” And love it he did.

Jobs told Isaacson about an early job he had in a Hewlett Packard assembly plant, which he received, amazingly, after calling CEO Bill Hewlett at home to bum some electronics parts. “I remember telling one of the supervisors, ‘I love this stuff, I love this stuff,’ and then I asked him what he liked to do best.” Using coarse language, the supervisor blurted a ribald answer.

Jobs was in love with Apple’s software and hardware and so, of course, he did some silly, love-struck things. But it was that overwhelming love which permitted those products to be conceived in the first place.

The Innovation Conundrum

By its nature, business lives in the cold, hardheaded world of finance and accounting, with bean counters at every corner. Any accountant worth his or her salt could easily see that Jobs was “wasting” money or taking too many risks. But through his love, Jobs ended up solving one of the biggest and most vexing business problems of our day. His key discovery could be as important as Henry Ford’s seminal production lines: Jobs may have figured out how to make large companies actually function properly.

What do love and sexy products have to do with making businesses function well?

To answer that question, it’s important to realize that one of the basic problems with large organizations is that people are hired and promoted because they look like good employees irrespective of whether they really are good employees.

The employee who gets promoted in a large organization is the one who shows up on time, looks like he or she is working hard, appears alert in meetings, can say a few confident statements when required, dresses nicely, has a firm handshake and a self-assured smile, and can adroitly choreograph PowerPoint presentations.

The employees who have a hard time are those who, like Jobs, challenge the status quo by championing new and untested ideas, approaches, or technologies. This second type of employee would be butting heads with others in the company, doing original work, and would have less time and patience to politely run meetings and create fancy slide decks. The second employee would focus more on future products and services, to the detriment of the current ones. This employee might seem insubordinate and even dangerous.

Know Your Customer

For the typical employee of a large organization, the true customers—the purchasers of the employee’s services and the determiners of the employee’s success—are that employee’s immediate coworkers and managers. In other words, each employee is strongly encouraged to satisfy his or her internal customers and only weakly encouraged to satisfy external, or “real,” customers.

Who will get more power and promotions at the typical large organization? The first type of employee. Who will help the company develop a new product that will define a new market and create millions of enthusiastic customers? The second type of employee. Large companies are unwittingly designed to favor employees who focus on their immediate, internal customers, solidifying the status quo and discouraging innovation. Large companies are designed to stagnate and eventually fail.

Microsoft, a company with a spotty record of creativity and innovation, has institutionalized such a crippling policy. Microsoft has failed at about every new product it has tried out on the market in the last decade, coasting instead on its unassailable Windows and Office franchises. (We’ll have to see how customers react to the new Windows 8 operating system, Surface tablet, and Windows phone.) Microsoft employs a management technique known as “stack ranking.” According to a former software developer, “If you were on a team of 10 people, you walked in the first day knowing that, no matter how good everyone was, 2 people were going to get a great review, 7 were going to get mediocre reviews, and 1 was going to get a terrible review. It leads to employees focusing on competing with each other rather than competing with other companies.” In other words, focus on the guy next to you and ignore the customer.

What did Jobs do that was so different? He understood what his customers would want years into the future and he cared enough about them to cause himself and those around him to suffer to achieve great things. As an über-customer himself, he pushed that perspective down through the organization. Here is what Jony Ive, senior vice president of industrial design at Apple, said at Steve Jobs’ memorial service at the company: “While the work hopefully appeared inevitable, appeared simple and easy, it really cost. It cost us all, didn’t it? But you know what? It cost him [Jobs] most. He cared the most. He worried the most deeply.”

Jobs effectively told those below him to create products that he could fall in love with, or to get out of the way. This brusqueness defined Jobs’ business interactions and he left a legacy of highly inspired and productive employees, along with a trail of broken, sore former employees.

Apple’s success comes partly because Jobs avoided the country club attitude where people try to be nice and to make other employees like them. Being overly nice fosters the status quo and can be vanity in disguise. After watching Jobs berate a hotel clerk for a substandard room, Jony Ive realized that most people, himself included, tend not to be direct when they feel something is shoddy because they want to be liked, “which is actually a vain trait,” as Ive reflected. People who are trying to achieve great things do not have the luxury of vanity.

Jobs ruffled many feathers and stepped on many toes, but he created an environment at Apple where the employees were directed to focus on the real customers and not their internal customers.

When we fall in love, many of us do silly, unproductive things, but the relationship is well worth the costs incurred. Jobs’ love helped to create a company, Apple, where employees are required to be good and not just look good. Even more, thanks to Jobs’ love, there are an incredible number of new electronic devices on the market—from iPods to MacBooks to iPads—that have changed the world. They are objects that, following Jobs, many of us have fallen in love with.