As the war between Russian forces and Chechen separatists grinds on, a new danger has emerged: the spread of violence beyond Chechnya and across the entire North Caucasus. Moscow has begun to make some advances against the Chechen insurgents, allowing it to reduce its troop levels and devolve more power to elected pro-Russian Chechens (even though many of them are violent, corrupt personalities with agendas of their own). But in the rest of the North Caucasus the Kremlin is fast losing control of the situation. Not only has it failed to take effective measures to bring stability, but it seems unable to understand the roots of the problem.

The tumult in Russia's Deep South has many causes, among them joblessness, ham-handed policies by leaders for whom Islam is a synonym for radicalism, pervasive corruption, the growing salience of Islam as a means for social protest, and the increasing restiveness of nationalities divided by arbitrary Soviet-era borders. If one adds to this list of complex problems the increasing resonance of chauvinistic and anti-Muslim groups and ideologies in Russia—a country with many millions of Muslims—the picture that emerges about Russia's future direction is disturbing.

A Widening Conflict

The seven Muslim republics of the North Caucasus region—Chechnya, Adygea, Dagestan, Ingushetia, Karachaevo-Cherkessia, Kabardino-Balkaria, North Ossetia—constitute a mere fragment of the Russian Federation's territory (0.66 percent) and population (4.6 percent). Yet these statistics mask the asymmetry between the size and the political significance of the North Caucasus, for this southern Russian borderland could prove to be the tail that wags the Russian dog. The fallout from Chechnya's war is enveloping the North Caucasus, the escalating violence nourished by deep social and economic pathologies. The consequences could reach far beyond this remote area.

Ironically, the widening of the conflict is due partly to Moscow's recent successes in Chechnya. Although hardly free and fair, a constitutional referendum and presidential and parliamentary elections have been held, and the pro-Moscow Chechen government has been assuming a larger role in battling the separatist forces, whose effectiveness has diminished. Much of the fighting now pits Chechens aligned with Russia against those seeking independence.

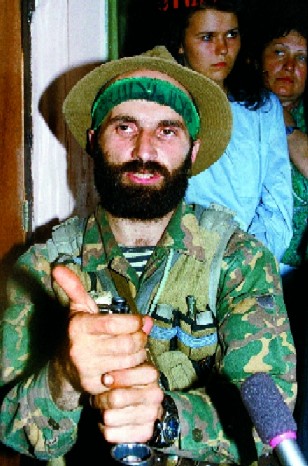

| Chechen fighters have widened the conflict, forcing Russians to extend themselves across the North Caucasus. |

Although this policy of “Chechenization” could lighten the burden borne by Russian troops, it has created two other problems. First, the Kremlin has become dependent on the reviled Ramzan Kadyrov, the son of Akhmad Kadyrov, the Moscow-backed president assassinated by Chechen separatists in May 2004. The younger Kadyrov, who was elevated to the post of prime minister in March 2005 with the obvious blessing of Vladimir Putin, is in reality the most powerful figure in Chechnya's government and overshadows Alu Alkhanov, the president, who holds what is theoretically the top position. But because Kadyrov is notoriously corrupt and controls paramilitary formations renowned among Chechens for lawlessness, his increasing power—he could become Chechnya's president in the next election—could dash Moscow's hopes of withdrawing the bulk of its forces and entrusting Chechnya to a stable and loyal regime. Second, faced with setbacks at home, the radical Chechen fighters have decided to widen the conflict so that Russian forces must extend themselves across the North Caucasus and are unable to concentrate solely on Chechnya.

| Thanks to Russia's policy of "Chechinization" much of the fighting is now Chechen vs. Chechen—those aligned with Russia against those seeking independence. |

The widening of the conflict is also attributable to the growing salience of Islamic radicalism. Since the March 2005 slaying of the secular-nationalist Chechen leader, Aslan Maskhadov, by or at the behest of the Russian security services, the political balance within the armed oppositions has shifted in favor of those whose declared objective is an Islamic caliphate uniting the North Caucasus. The most famous of the field commanders, Shamil Basayev and Abdul-Khalim Sadulaev, Maskhadov's successor, symbolized this change. Sadulaev was killed during a clash with Russian forces in June 2006, and Basayev died in July under circumstances that remain unclear. Their speeches and proclamations brimmed with Islamist discourse and visions of a sharia-based polity uniting the region. Although Maskhadov's death was celebrated by the Kremlin, it has in reality made its problems worse. Maskhadov, who had declared a unilateral cease-fire just before his death, did not necessarily seek an independent Islamic state in Chechnya, let alone a sharia-based caliphate in the North Caucasus; the current anti-Russian Chechen leadership does. Maskhadov may have accepted far-reaching autonomy within Russia (indeed, while painting him as an extremist, the Kremlin periodically conducted back-channel negotiations with his representatives); Basayev and Sadulaev did not. And even if it could be proven that most Chechens now wish to remain within Russia—surveys indicate they do—radical Chechens fighting for an independent Islamic state will hardly quit.

Contrary to the Kremlin's storyline, however, the growing havoc in the North Caucasus is not generated chiefly by Al Qaeda terrorists, foreign purveyors of Salafiyya Islam (Sunni movements' advocating an Islamic state based on sharia law and the pristine Islam practiced by the first generation of Muslims), or the machinations of like-minded Chechens. As elsewhere, Islam in the North Caucasus is multifaceted; Salafiyya strains are new arrivals, with shallow roots compared to the historically dominant mystical Sufi tradition, which Salafis condemn as virtual apostasy. Although Islam is certainly emerging as a paradigm for understanding and changing the region's squalid present, this is because the squalor is invasive and intractable. Poverty and corruption are ubiquitous. Local leaders, communist-era holdovers in the main, are widely seen as crooked toadies of Moscow who rule like pashas. Unemployment is massive, running as high as 70 percent in parts of the North Caucasus. Ethnic tensions suppressed by the Soviet system have surfaced. Stalin shoehorned diverse nationalities into capriciously created political units, separating them from their kin—an arrangement that now promotes territorial disputes and secessionism. The collapse of communist ideology and institutions produced an ideological vacuum and a quest for alternatives. Together, these conditions are the context of instability and, in substantial measure, explain radical Islam's appeal.

The First Domino

Moscow lacks a coherent policy to address these problems. Putin and his inner circle seek to ascribe the violence in the Muslim south to terrorism and “Wahhabism” (a catchall term applied to any admixture of Islam and politics), seeing tougher law enforcement and military operations as the solution. But the arbitrary arrests of Muslims, blanket closure of mosques, and rough tactics by corrupt and discredited police and security forces have alienated the populace further, increasing (even if only among a minority of the population) the lure of the militant variant of Islam propounded by the late Basayev and Sadulaev. Paradoxically, then, the Kremlin and Chechnya's radical Muslim fighters are allies, albeit unwitting ones.

| War is seldom an ally of freedom, and Russian democracy could be stifled if the violence in the North Caucasus spreads. |

No matter the challenges, Moscow will not relinquish this region, which is pivotal for many strategic reasons. But most important, the Kremlin likens the North Caucasus to the first domino, which, if allowed to fall, would spawn revolts in Russia's other ethnic republics.

Yet a Russian policy that rests principally on force alone will fail, especially if it features the abuses that have marked the campaign to quell Chechnya. Worse, escalating violence in the North Caucasus could widen the gulf between Muslims and ethnic Russians in Russia's heartland. Russia's Muslim citizens—currently 14.5 million strong—are becoming increasingly organized politically, partly because of the nationalist, Russia-for-the-Russians rhetoric of chauvinistic groups within Russia that resonates even among some leaders of the Orthodox Church. A spate of terrorism generated by mounting violence in the North Caucasus could increase the appeal of such extremism for ethnic Russians and produce an anti-Muslim backlash that sows the seeds of communal conflict.

A spiraling conflict in the North Caucasus and a polarization between Muslims and ethnic Russians elsewhere in the country could destroy such calm as presently exists. The consequences of religious violence could be even graver given the differential in birthrates between ethnic Russians (low) and Russian Muslims (high) and the projected decline in Russia's overall population.

| A Russian policy that depends on force alone will fail, especially if it features abuses of the kind that have marked the campaign to quell Chechnya. |

A full-scale war in the North Caucasus, even an endless string of insurgent attacks, could also accelerate the slow-motion authoritarianism already evident in Russia's politics. Terrorist attacks could increase the appeal of Russian fascist organizations, which already portray Muslims, as well as dark-skinned Christians such as Georgians and Armenians, as unwelcome “others” who either do not belong in Christian Russia or should inhabit it under terms set by Russians. Although these attitudes hardly represent mainstream attitudes in Russia, Russian public opinion polls indicate that they are gaining traction, particularly among youths. War is seldom freedom's ally, and Russia's democracy could also be stifled if the violence in the North Caucasus extends to the rest of the country and prompts the state to increase the power and leeway of the security forces and to curb civil liberties in the name of security.

What the Future Holds

The entire North Caucasus is awash in violence and turmoil, and there is little reason to believe, despite the recent gains the Kremlin seems to have made in Chechnya, that things could get better. The Putin government is responding to the escalating instability by trying to increase its power at the expense of corrupt and incompetent local leaders. But this policy could overload the center and provoke a backlash from local elites determined to defend a status quo that gives them wealth and power. Chechnya, Dagestan, and Ingushetia look to Moscow for approximately 80 percent of their budget; the other North Caucasus republics are only slightly less dependent.

Then there is the human and material price of a conflict that continues to spread beyond Chechnya. By conservative estimates, the war in Chechnya costs the Kremlin $1.5 to $3 billion a year; 16,000 Russian military and security forces (and as many as 60,000 civilians, many of them ethnic Russian residents) have died in Chechnya since 1994—about the number who were killed during the 1979–89 Soviet war in Afghanistan. Roughly 250,000 military and security personnel are now stationed in the North Caucasus, a figure that amounts to nearly one-third of the army's manpower and four out of five of the Interior Ministry's divisions. These burdens will become even heavier if the rest of the North Caucasus becomes a war zone.

Yet even a quarter of a million military and security personnel seem to be insufficient. The Interior Ministry and the Ministry of Defense are deploying additional forces to the region. But a military solution is unlikely to prove any more successful than it has in Chechnya. The North Caucasus already contains 1,180 siloviki (security personnel) per 100,000 people, making it among the most militarized areas in the world.

Another risk in using the blunt instrument of military force to deal with the growing unrest in the North Caucasus is that Russian forces are likely to use the same brutal tactics (kidnapping, torture, rape, and summary executions) that have become their signature in Chechnya, particularly because the increasing unpopularity of the war at home (opinion surveys taken in December 2005 show that 85 percent of Russians are pessimistic about the situation in the North Caucasus) has forced Putin to stop sending conscripts to the war zone and to rely instead on paid volunteers, the kontrakt-niki, who are infamous for brutalizing civilians. If the tactics used in Chechnya are applied elsewhere in the region, the resulting alienation, anger, and radicalism will swell militant Islamists' ranks.

| The Kremlin likens North Caucasus to the first domino, which, if allowed to fall, would spawn revolts in Russia's other ethnic republics. |

But there are perils beyond entrapment and rising human and financial costs. One is an increase in terrorism. Chechnya has been the origin of many major terrorist attacks in other parts of Russia, and the radicalization of the North Caucasus will only increase the supply of extremists who see terror as an appropriate weapon. An open-ended war between Muslims and federal forces in the North Caucasus could precipitate violence between Russian ultranationalist groups and Muslims in other Islamic republics. The third danger centers on Russia's southern neighbors. If Islamic extremists establish secure footholds across the North Caucasus, the political equation in Muslim Azerbaijan and Central Asia could also be changed. Autocratic regimes rule both regions through rigged elections and intimidation and resist opening up the political process. Islamists from the North Caucasus would be positioned to help—and to seek assistance from—like groups in these nearby regions, both materially and by virtue of their example. Russian officials already fear that instability beyond the southern border could present new and formidable security threats.

These various scenarios may seem unlikely now, but if the recent political history of the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies has taught us anything, it is surely that tomorrow may be quite unlike today.

The content of this article is only available in the print edition.