South America’s most serious threat of regional conflict in several decades erupted and receded during the first week of March, and most people in the United States didn ’t even notice. A shooting war between Colombia, on one side, and Venezuela and Ecuador, on the other, was averted—but there was no resolution of critical long-term regional disagreements. Indeed, these continue to grow more serious, not least because of information discovered in the computers of a dead Colombian guerrilla that may force Washington into a showdown with Venezuela.

What precipitated the crisis, and why should North Americans care? The trigger was simple enough, even though news reports and most Latin American leaders were quick to muddy the waters. A band of guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) from Colombia ’s Putumayo province retreated into what they considered a safe haven just two kilometers into northern Ecuador. Because the group included Ra úl Reyes, the number-two leader of the FARC, the Colombian government decided it couldn ’t miss the opportunity to take him out, which it did, along with twenty-four others.

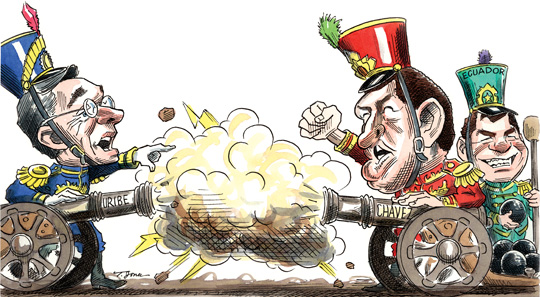

In the debris of the Ecuadorean guerrilla camp, Colombian forces found Reyes’s body and his laptops, which reportedly were full of information about FARC that the world was not supposed to know, including evidence of secret support from Venezuela and Ecuador. (As of early April, Interpol was examining the laptops and messages to determine if they are authentic.) Ecuador ’s President Rafael Correa protested the Colombian incursion and traveled around the Americas lining up other presidents to stand behind him. Predictably, it was Venezuelan leader Hugo Ch ávez who led the charge against Colombian President Alvaro Uribe Vélez; Chávez mobilized troops on the border and threatened trade boycotts and war.

After a week of saber rattling and dire threats, the three presidents suddenly declared a truce March 7, and the Organization of American States (OAS) sent a commission to investigate the near clash. Uribe, whose incursion was supported by 83 percent of Colombians, apologized and said he would not repeat the action. Chávez and Correa reportedly agreed to fight threats to regional stability arising from irregular or criminal groups. But although regional military conflict is probably no longer an immediate danger, popular frustration seethes and problems multiply in the Andes region. And Chávez and Correa have their own definitions of key terms of the agreement.

THE U.S. STAKE IN THE CONFLICT

Americans who support the development of functioning democracies and free markets should take a vital interest in what is happening in the northern Andean countries. Nowhere else in the Americas does a single region offer such clear and contrasting versions of domestic and international life, a virtual laboratory in which to test two contrary perspectives. Colombia has a democratic, pro-American government and for many years has had a reasonably productive market-oriented economy, despite decades of internal warfare against Marxist guerrillas, paramilitaries, and drug lords. Venezuela, on the other hand, has a militantly anti-American, increasingly authoritarian populist government, with an oil-rich but nonetheless grossly mismanaged and troubled economy. Venezuela in many ways apes all other failed populist regimes, though with a stronger international agenda.

Most of Latin America is full of frustrated people who are badly served or mistreated by their governments. Those people, who vote under conditions that often are only formally democratic, are courted by self-proclaimed Chavista messiahs like Correa in Ecuador and Evo Morales in Bolivia. Those two and other messiahs have turned to using democracy according to their own lights to consolidate personal power with the goal of remaining in office permanently. There are also democratically elected Chavista or Chavista-tilting leaders from Nicaragua to Argentina, and Chavistas have nearly won presidencies in places like Peru and Mexico.

Governments in Brazil, Uruguay, Chile, Peru, and Mexico are striving to develop and stave off Chavismo, though the results will depend on how successful they are in serving popular needs and aspirations. Always in the wings are demagogic leaders who play on and manipulate legitimate frustrations and offer the favorite cure-all of the day, now “twenty-first-century socialism,” a Chávez concoction that carries the torch of Cuba’s Fidel Castro, the recently retired anti-American icon of generations past.

Colombia is tangled up in the web of the disruptive—and destructive—war on drugs. For many years, Colombia has been the main recipient of U.S. aid in the Americas; since 2000, that support has totaled $5 billion, most of it military aid that has contributed much toward weakening FARC and improving national stability. FARC began decades ago as the military wing of the pro-Soviet Communist Party of Colombia, and it has been terrorizing, killing, and kidnapping Colombians ever since. After the collapse of the Soviet bloc and its financial and logistic support, FARC had to find another way to sustain itself; in Colombia that predictably meant drugs. FARC holds hundreds of prisoners in the jungles and mountains, who now serve above all as shields to discourage government attacks on top FARC leaders.

FARC membership (according to official Colombian estimates, about 6,000 fighters) has declined by two-thirds since Uribe became president. A week after Reyes’s death, a second member of FARC’s seven-member ruling body was killed by his own bodyguard. But FARC remains a dangerous force, and many governments, including those of the United States and the European Union, brand it a terrorist organization. Ch ávez and Correa, to the contrary, want FARC to be classified as a legitimate belligerent in Colombia; indeed, the Venezuelan president has called FARC a liberation movement and brands Uribe’s government a “criminal . . . terrorist state.”

Chávez’s hostility appears to go beyond bluster. If the files on the laptops found after Reyes ’s death prove authentic (Correa and Chávez have naturally called them fakes), the years of rumors of Cávez involvement with FARC will be shown to be true, with significant implications for the future. According to a Washington Post article by Jackson Diehl, the files included a plan to sanitize the FARC internationally and then have it put forward a Chavista presidential candidate in the next Colombian elections (not an entirely bad idea, although FARC has its own tragic history in Colombia). FARC needs sanctuaries and supplies, and Chávez is eager to support any group that will fight America and its allies; he has spent billions of dollars arming Venezuela for what he warns is an almost inevitable confrontation with the United States. His key Andean goal is overthrowing the most unequivocal U.S. ally in South America, Colombia’s Uribe.

But now a link between Chávez and terrorists, if proven, may force Washington either to deny the connection or to break ties with Venezuela and cut off purchases of its oil. The United States could adjust to such a cutoff with an effort, but the Venezuelan economy would be hit hard; its heavy oil is unusable for most purposes unless it is refined, and most of the refineries used by Venezuela are in the United States. Conspiracy theorists might even argue that the CIA planted the laptops to force the U.S. government to cut the oil bonds between Washington and Caracas and, in so doing, throw Venezuela into a crisis sufficient to topple Chávez or perhaps set him to attacking his neighbors.

Also among the laptop revelations, as reported by Jane’s Terrorism and Security Monitor on April 4, were messages indicating Correa’s knowledge of and support for guerrillas using border camps. Stored e-mail messages show that there were relatively fixed FARC camps in Ecuador, which were known to at least some of Ecuador ’s military commanders, and that Ecuador’s president not only wanted the camps to remain well-stocked safe havens but was willing to remove military leaders who objected.

HARD QUESTIONS ABOUT SOVEREIGNTY

Uribe characterized Colombia’s response to the guerrillas, and to regional criticism of the Ecuador incursion, as follows: “We are not warmongers, but we are not weak. We cannot allow terrorists who seek refuge in other countries to spill the blood of our countrymen.”

Most Latin American leaders reacted predictably to the crisis of early March. As soon as the border crossing was reported, they repeatedly invoked the national sovereignty of Ecuador, as if by repetition they could treat a complicated problem as a simple matter of law. To be sure, it is desirable to defend national sovereignty, but the nature of this complex border case was left unexamined: principally, the possibility of state-sponsored terrorism. Tal Becker, an international lawyer and a legal adviser to Israel ’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, wrestled with similar issues in his book Terrorism and the State: Rethinking the Rules of State Responsibility. Becker articulates “a causation-based system of state responsibility for terrorism.” He acknowledges the difficulty of assigning that responsibility, but concludes that “to protect the foundations of the international system . . . it is necessary to see in state toleration of terrorist activity, or its failure to prevent it, a fundamental violation of the covenants made both between states and within them.”

Using this as a guideline, and considering the messages on Reyes’s computer, it is clear that Colombia’s sovereignty was effectively violated by Ecuador’s knowingly harboring the FARC terrorists.

Statements by the Organization of American States placed responsibility for the incursion on Colombia and reaffirmed its absolute defense of the “national sovereignty of Ecuador.” One resolution presumably committed all member states “to combat threats to security caused by the actions of irregular groups or criminal organizations, especially those associated with drug trafficking. ” But the OAS did not acknowledge that the March 1 attack came precisely because Ecuador was failing to combat those threats inside its own borders. Nor did it clearly define its terms so that Chávez and Correa could be held to the OAS promise. Chávez’s compliance will be very difficult to monitor, compared to Uribe’s commitment not to invade again.

Colombia’s strike rejected the idea that international law permits terrorists to attack and then to flee with impunity to a neighboring country that tolerates or even supports them. Just a week before the Colombian action, the Turkish military launched a multiday invasion into northern Iraq to wipe out Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) forces that were attacking Turkey from sanctuaries there. If international law does not sanction self-defense in such cases, it ceases to be relevant in some of the most explosive areas of the world, where it is desperately needed.