David Petraeus famously asked about Iraq, “Tell me how this ends?” In this year of taking stock of America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and weighing the record of the global war on terror, the retired general’s question is more pertinent than ever. Last summer, President Obama announced his plan for removing U.S. forces from Afghanistan, establishing a timetable that is to conclude in 2014. In so doing he displayed the clearest difference in national security policy between his administration and that of his predecessor: over when, and how, to bring American troops home from the battlegrounds where they were sent to fight in the wake of 9/11.

President George W. Bush was emphatic from the beginning that troop levels would be established by commanders on the ground, “not by artificial timetables set by politicians in Washington.” In fact, four years ago, using only the second veto of his administration, he vetoed legislation establishing a timetable to withdraw from Iraq. Bush administration strategy was based on the belief that societies in transition need to be supported for as long as it takes their governments and security forces to become capable of doing the work that U.S. military forces were performing. Only in the context of confidence about American commitment, it was believed, would factions that were fearful and divided from decades of authoritarian rule or civil discord come together.

By contrast, Obama administration strategy flows from the premise that societies in transition need deadlines to spur progress—that the American drawdown will force them to take responsibility for their governance and security. Sensible enough in the abstract, but what the Bush administration understood that the Obama administration seems not to is that threatening fragile governments with abandonment does not produce an environment conducive to brave political choices. It has not in Iraq, where Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki chose to hedge his bets by forming a government with the virulently anti-American Sadrist party. And it has not in Afghanistan, where President Hamid Karzai is blaming the United States for the incapacity of his government.

Nor does a fixed timeline encourage allies and enemies to trust American commitments or give them incentives to follow our guidance. The Pakistani government’s current touchstone for thinking about its relationship with the United States was established in 1998 when Washington cut off aid after Pakistan’s nuclear test. While understandable in the context of seeking to penalize nuclear proliferation, cutting ties to Pakistan had significant unintended consequences, including producing a generation of Pakistani military officers who have little knowledge of or support for American concerns. Our single-minded focus on nonproliferation failed to encompass the range of other issues on which we might need Pakistan’s help.

One of those issues is managing the threat of terrorism. Pakistan—both its government and its people—is deeply skeptical of American motives. This is obvious from its grudging cooperation with our operations. Afghans are suspicious too; they experienced abandonment by the United States when the Soviets withdrew. Obama’s timelines encourage both our enemies and our potential allies in the region to distrust our staying power. They do not believe we are committed to the fight, and as a result do not want to invest too heavily in cooperating with us.

THE CIVILIAN SIDE FALTERS

In both Iraq and Afghanistan, our strategy has been a gradual transition from American to indigenous control of military operations, coupled with an intensive program to build military and police forces that can protect their own societies and improve the capacity of local and national governance. Our military has done its part bravely and steadfastly.

Where our strategy has run into trouble in both Iraq and Afghanistan has been the capacity of American civilian agencies to capitalize on military gains, as well as the capacity of Iraqi and Afghan governments to take responsibility under our timetable. This reliance on civilian capacities in our own government and the government of the nation we are fighting in makes it harder to achieve our military objectives.

Difficulties aside, those partnerships are not a bad strategic choice, especially partnerships with the country in which we are operating. We want an Iraq and an Afghanistan capable of governing their people well and controlling their territory to prevent recurrence of the threats we invaded them to destroy. As the great English parliamentarian Edmund Burke said, “The use of force alone is but temporary. It may subdue for a moment but it does not remove the necessity of subduing again; and a nation is not to be governed that is perpetually to be conquered.” Americans especially should ponder that advice, because it was our own American colonies Burke was trying to persuade his fellow Britons to govern well.

But neither Iraq nor Afghanistan has progressed in developing governance or security forces under the timetable expected by the U.S. government. Iraq appears to have become strong enough to manage its internal frictions and external threats, but that outcome is by no means assured, as a recent increase in deadly attacks made clear. Maliki has been expressing optimism that Iraq’s security forces are up to the task since 2005. Iraq’s former defense minister, Abdul Khader, and its military leaders have repeatedly said they need the assistance of American military involvement until at least 2015. But Maliki is now also the defense minister, and because he has formed a government with the support of Muqtada al-Sadr’s pro-Iranian political party, it is virtually assured that there will be no renegotiation of the agreements removing all U.S. forces from Iraq before the end of this year.

Not that the Obama administration has seemed to want a continuing relationship anyway. Its attitude has been one of confidence that soft power can guarantee that the gains so dearly bought in Iraq can be maintained and capitalized upon.

EXPENSIVE AND UNCERTAIN

The State Department, for instance, has astonishingly ambitious plans for the transition to civilian control in Iraq. “We are in the midst of the largest military-to-civilian transition since the Marshall Plan,” reads the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review, the blueprint for projecting U.S. civilian agencies’ power abroad. “Our civilian presence is prepared to take the lead, secure the military’s gains, and build the institutions necessary for long-term stability.” The Senate Foreign Relations Committee has expressed serious reservations, questioning whether the State Department can sustain its proposed presence in Iraq without military support, and challenging the cost-effectiveness of consulates’ requirement of 1,400 security and support personnel for 120 diplomats. If a complete withdrawal of U.S. troops (except staffers in the Embassy’s Office of Military Cooperation) is to remain U.S. and Iraqi government policy, the Foreign Relations Committee recommends that “given the prohibitive costs of security and the capacity limitations of the State Department, the United States should consider a less ambitious diplomatic presence in Iraq.” The Government Accountability Office is also less than enthusiastic about State’s ability to plan and carry out its proposed activities in Iraq.

The State Department responds that its plan would produce enormous savings over the current cost of operations in Iraq. That is certainly true. But also inescapable is that the United States will be getting an awful lot less value than it has obtained from having fifty thousand U.S. troops in Iraq. Moreover, an inexpensive failure is no bargain. The $5 billion annual cost of civilian-led operations in Iraq will be the largest single item in the State Department’s budget, and twice the size of its current spending for Iraq. Every organization that has looked into the transition to “leading through civilian power” in Iraq has deep reservations about State’s ability to carry it out.

Afghanistan presents an even greater difficulty. Marines in Marja are still waiting for the “government in a box” that was to capitalize on U.S. military gains. And even though the State Department has increased government civilian personnel in Afghanistan from three hundred to nearly a thousand, governance efforts are so weak that military operations are subsuming the tasks of building governance, including running the task force fighting political corruption in the Afghan government (a task force led by Brigadier General H. R. McMaster, a Hoover research fellow).

Even the bread and butter of diplomacy—engaging the government—has largely fallen to the military because the civilian leadership has failed to develop positive relationships in Afghanistan. That the administration left Ambassador Karl Eikenberry in place, even after the release of diplomatic cables in which he described Karzai as mentally unsound, gives a sense of how little commitment the administration has to producing the “whole-of-government operations” claimed to be the hallmark of its international engagement.

We need to put our wars on a solid footing and draw them to a responsible close. To fulfill this mission—the objective the administration emphasizes for both Iraq and Afghanistan—we must first give the military time to dominate the security environment. Obama’s announced drawdown in Afghanistan is more than six times the reduction recommended by U.S. military leaders and endorsed by outgoing Defense Secretary Robert Gates, who stressed the importance of front-line fighting forces consolidating gains in the south and taking the fight to the last eastern strongholds of the Taliban, the enemy whose sheltering of Osama bin Laden provoked America to invade after 9/11. Gates, who had initially rebuffed calls for a large troop reduction, said, “We can do anything the president tells us to do; the question is whether it is wise.”

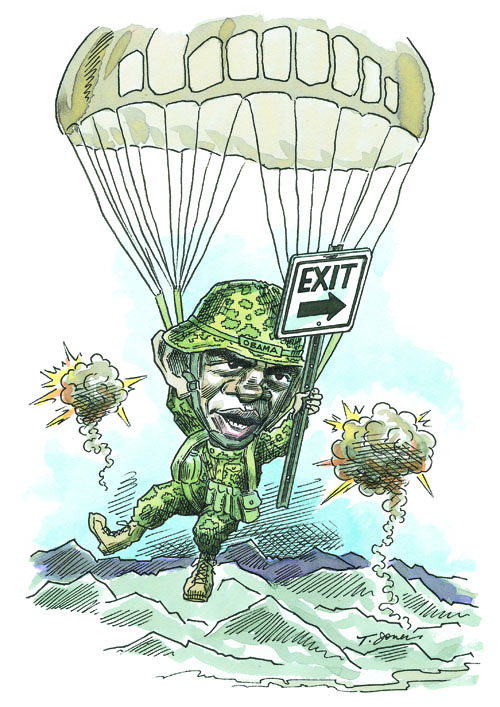

Wisdom also demands that we train indigenous security forces for the necessary tasks, build governance of the kind that will give these new governments legitimacy with their own people, and pursue vigorous diplomatic engagement with other countries that can contribute to an international environment supportive of our aims. The president’s rush to the exit door makes all these tasks more difficult.