Is Raúl Castro simply a clone of his elder brother Fidel? Answering that question is a step toward ending what may be the most prolonged and divisive dispute in the history of modern U.S. foreign policy.

During the Cold War, trying to isolate Cuba served American security interests since Cuba was an ally of the Soviet bloc. But since the fall of the Soviet Union, U.S. policy toward Cuba has focused on “nation building” and mild agitation to eliminate the Castros. Analysts who reject these as adequate grounds for foreign policy can also critique the current policy on its own terms. In other words, has it been successful in nation building? And more importantly now, have Raúl’s reforms since taking the top office in 2006 really begun to change conditions in the country?

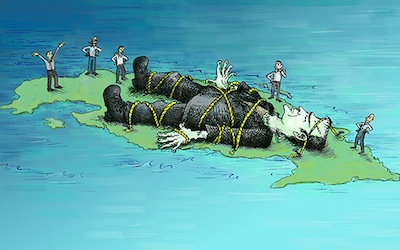

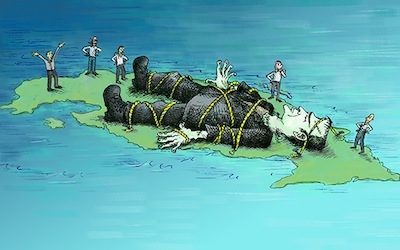

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

Distinguished analysts differ on the merits of Raúl’s reforms. Economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago calls them “the most extensive and profound” changes on the island in decades, though still inadequate, while Carlos Alberto Montaner calls them “token gestures.” In May, I made a two-week visit to Cuba, my sixth since 1983 as a journalist and lecturer, to see what I could learn on the ground. I found the prospects for meaningful reforms were encouraging but preliminary.

Conditions and Changes

I surveyed Raúl’s specific responses to Cuba’s challenges last January in an essay titled “Cuba’s Tortured Transition,” so here I will focus on the individual, cultural, and institutional factors that now complicate substantive reform on the island.

Raúl and the Cuban Communist Party speak of “updating the economic model,” which is either a feel-good phrase devised to mask criticism of Fidel’s economic failures while changes are slipped through, or an admission that those in charge are not serious reformers. Changes are explicitly made in the service of “socialism,” which begs the question: Despite some promising new policies, will change still be inhibited by Cuba’s official ideology and ideologues?

Former high-level Cuban officials who worked closely with Raúl and coauthored articles with me note his early interest in serious, systematic, long-term economic reforms like those that have been undertaken under authoritarian regimes in China and Vietnam. If Cuban leaders were free to think outside the socialist box, their best reform model would be Taiwan, which is a democratic market economy. Realistically, however, Cuba will not now move toward democracy and thus it’s more likely China and Vietnam are models for its future. Raúl’s current presumptive heir apparent, Vice President Miguel Diaz-Canel, visited both China and Vietnam in June.

The Castros have never respected individual rights, though they claim to do so with education and preventive health programs for all. But in these and other socio-economic fields, Cuba ranked high among the Latin American nations before the Castros hit the scene, and this was despite an imbalance between urban and rural sectors. Since then, Cuba has fallen in the rankings. The United Nations Development Programme’s 2013 Human Development Index rates Cuba fifty-ninth in the world and sixth in Latin America, a respectable but not stunning record. The 2013 Human Rights Watch World Report concluded that Cuba “represses virtually all forms of political dissent.” Economic freedoms are just beginning to sprout.

Frankenstein in Havana

Cuban professor Carlos Alzugaray has underlined the gravity of Cuba’s economic problems today by using what he calls the “Frankenstein metaphor.” Speaking recently at Stanford University, he said Fidel’s economic policies were meant to be a gift to mankind, like Frankenstein’s creature. But like the scientist’s creation, they turned out to be “monsters.” Though Alzugaray did not openly criticize “Father” Fidel, he noted the latter’s flawed insistence on state control of all economic policy and his long opposition to the free market, individual initiative, and entrepreneurship.

Fidel’s freely chosen economic plan was, over the course of a half-century, uniformly disastrous. From the Revolutionary Offensive in 1968, with its crushing of even one-person private businesses, to the fanatical 1970 sugar program that destroyed the then-fairly balanced Third World economy, to the quick reversal of earlier concessions to individual initiative in times of economic collapse, Fidel’s policies have paralyzed the nation.

Fidel was one of modern history’s most arrogant and inflexible leaders. He would not learn anything from anyone or anything. He never learned about economics or human nature from his own disastrous failures nor from the collapse of the Soviet bloc. He did not even learn from the experiences of China and Vietnam, clearly “revolutionary” governments that finally saw the necessity of market economics.

Fidel’s Cuba is a case study in the tragic waste of opportunity and life that is inevitable under a Caudillo Messiah with a paternalist utopian domestic agenda, an expansive revolutionary international policy and a totally closed mind. The key question is, what direction will the country take now that Fidel’s role is over or, at least, much reduced?

Raúl on Fidel’s Monsters

The most influential expert witness on Cuba’s economic condition today is Raúl, historically the more pragmatic of the brothers. Raúl has often focused on the problems of deeply ingrained attitudes that keep people from recognizing, openly confronting, and resolving problems. In 2011 he said bluntly that changing Cuba will depend on “transforming erroneous and unsustainable concepts about socialism, deeply rooted in broad sectors of the public for years, as a result of the excessive paternalistic, idealistic, and egalitarian focus that the Revolution adopted in the interest of social justice.” After a visit to Cuba last year the head of the Vietnamese Communist Party, one of Cuba’s oldest and closest allies, said publicly that what the Cuban people need most is “a change of mentality at all levels, from the highest level to the grassroots.”

At the same time, there are many obstacles that stand in Cuba’s way. Raúl has hinted at but downplayed the massive impact of Hispanic tradition. Fidel and his late acolyte, Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, are just the most recent in a centuries-long parade of Latin American caudillos or strongman dictators. Increasingly over the centuries caudillos acted like Messiahs and were thus welcomed in societies that seem to expect paternalistic leaders. The Messiahs rant at the Devils around them (i.e. America), promise miracles they cannot deliver and leave a mess behind when they finally go.

Another of Raúl’s most revealing critiques emphasizes the challenge of simply getting things done when people have little motivation and a weak work ethic. He relates that decades ago Vietnamese leaders asked Cubans to teach them how to grow coffee, which Cubans did. Vietnam soon became the second-largest coffee exporter in the world and a high Vietnamese official asked, incredulously, “How is it possible that you taught us to grow coffee and now you are buying coffee from us?”

As soon as he took over in 2006 Raúl warned, ”We’re tired of excuses in this revolution!” Cubans, he said, must “erase forever the notion that Cuba is the only country in the world where one can live without working.” Shouting slogans and scapegoating will no longer do, he has said repeatedly. The farmland is there waiting to be cultivated and jobs of all sorts are waiting to be created and done. These needs and problems were reiterated at party and National Assembly meetings in early July.

The Independence Fetish

One of Fidel’s most spectacular claims was that of Cuba’s independence. True, Cuba broke politically with the United States and he sometimes bit the Soviet hand that fed him. But economically he was almost always on the dole to foreigners who in various forms sent Cuba a quarter of its annual GDP. The Soviet bloc subsidized Cuba throughout the Cold War and when the aid stopped in the early 1990s Cuba’s economy crashed utterly.

Thereafter Fidel arranged heavy support from Chavez and even indirectly—after passing through individual Cuban recipients—from the United States. The latter came from Cuban-Americans—Fidel always called those exiles “worms”—who sent and still send remittances that, according to differing calculations, are today either the main source of foreign exchange revenue for the state or greater than all other sources combined.

Despite Raúl’s rhetoric, the official vocal enthusiasm for socialism seems as alive as ever in Cuba. Buildings and roadsides in the cities and countryside are plastered with slogans like: “The Revolution Moves Ahead, Vigorous and Victorious”; “This is the Hour of Our True Greatness” and “United, Vigilant and Combative in Defending Socialism.” Stultifying Cuban publications constantly rehash the great “triumphs” of the Old Guard revolutionary heroes decades ago. This kind of puffery is particularly pathetic these days given the depth of Cuba’s economic and political problems resulting above all from Fidel and the Revolution itself.

As in the past, the most common, cloying, and counterproductive image in Cuba is that of Che Guevara, the supposedly selfless “new man” who lauded moral over material incentives and was often even more violent, stubborn, and utopian than Fidel. The image of him appears all over the country, in posters, postcards, and a jarring 120-foot-high “silhouette-outline” of him on the Ministry of the Interior building in Revolutionary Square.

The truth is—as it has long been—that Che was far more useful to the Revolution dead than alive. First, he was not around long enough to threaten Fidel. Second, like the men and maidens on Keats’ Grecian Urn, Che “survived” not as the arrogant loser he so often was but in the unchanging glamorous photos of the forever macho young man in his prime.

So contradictions and inconsistencies abound and Raúl and his cohorts send mixed messages to the Cuban people and the world. Does Raúl really support serious reform; is he being sabotaged by mid-level bureaucrats and surviving ideologues, including Fidel; is he being thwarted by rampant corruption at all levels of society; are enough of the Cuban people willing to work hard and long enough to build and sustain a new economy and life? Perhaps.

Raúl’s reforms to date fall far short of what China and Vietnam have done and what is needed to bring Cuba into the economically developing world. Even so, more Cubans are moving in the right direction now than at any previous time in the past half-century. The bottom line for U.S. policy should be to let Cubans resolve their own domestic problems as best they can without frictions deliberately generated from abroad.