America has spent three decades and hundreds of billions of dollars fighting a national war on drugs. Has the war on drugs been an effective way of dealing with America's drug problem or does it cause more harm than good? How should we weigh the moral and utilitarian arguments for and against the war on drugs; in other words, do we need to intensify the war on drugs or is it time to declare a cease fire?

To view the full transcript of this episode, read below

Peter Robinson: Welcome to Uncommon Knowledge. I'm Peter Robinson. Our show today, The War on Drugs. Testimony before the United States' Senate by the Federal Council of Churches. I quote, "In dealing with gigantic social evils like disease or crime, individual liberty must be controlled in the interest of public safety." Later in the testimony and again I quote, "Traffic in these intoxicants is a social evil that must be destroyed. It means the degradation of families and needless inefficiency in industry."

No, the Federal Council of Churches was not testifying in favor of the war on drugs. It was testifying in favor of prohibition. Prohibition was enacted in 1920 with the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution. It banned the sale of alcohol throughout the United States. What happened? Consumption of alcohol did decline but only temporarily. A black market in alcohol arose, giving rise to violent crime and colorful figures such as Al Capone. And as for the hoped for improvements in family life and industrial productivity, they never materialized. From hooch to hash.

Today's war on drugs has been going on for more than thirty years at a cost, every year, of billions of dollars. Our question, simply this, is the war on drugs any more effective than was the war on alcohol?

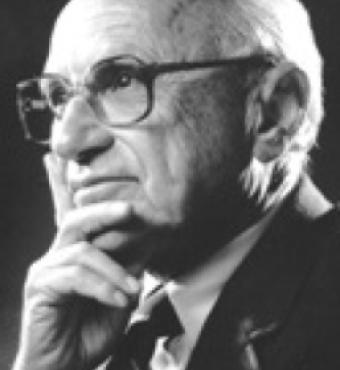

With us, two guests. Pete Wilson is the former governor of California. Governor Wilson is a staunch advocate of the war on drugs. Milton Friedman is a Nobel Prize winning economist. Dr. Friedman believes the war on drugs should be brought to an end.

Title: War, What Is It Good For?

Peter Robinson: The Economist magazine this past August, I quote, "If you want to see money thrown at a problem to no good effect, you need look no further than America's war on drugs." The war on drugs and no good effect. Pete Wilson?

Pete Wilson: Well I would disagree with that. The effort that is being made is to contain drug use, to prevent the kind of dysfunctional behavior, dangerous behavior, the neglect of children, all of the things that come from drug use of dangerous drugs, whether it is legal or illegal. And yes, it's expensive but I would argue that the alternative is far more costly.

Peter Robinson: No good effect. Milton Freedman?

Milton Friedman: Worse than no good effect. Many ha--harmful effects. We have been destroying other countries because we cannot enforce our own laws. The attempt to prohibit drugs has done far more harm than good.

Peter Robinson: Pete Wilson, listen to a few statistics. First declared by Richard Nixon, the war on drugs has gone on for more than three decades. This year, 2001, the federal government will spend more than nineteen billion dollars on drug control policies with state and local governments kicking in another twenty-two billion. So we're talking about something that's gone on for thirty years and has a current year price tag of over forty billion dollars. The price of drugs, heroin and cocaine, lower today than it was fifteen years ago. After dropping somewhat during the 1980's, drug use now appears to be rising. I cite one study, the percentage of high school seniors who used an illegal drug within the past thirty days, peaked at forty percent in 1980, drops to fourteen percent in 1992, but has now risen to twenty-five percent. You still wish to maintain that this is a good investment for the nation?

Pete Wilson: Yeah and I think the statistics that you are citing make the point that when we, in fact, actually engaged in a serious national effort, which didn't began in really until about 19--the mid 1980's. For a seven year period ending in '92, it had the effect of su--substantially containing the problem.

Peter Robinson: Okay, what about these distinctions? When you have somebody who is serious about it, you can actually accomplish something?

Milton Friedman: I don't think, first of all, the most important thing is you're not looking at the real cost of the attempt to (?) the drug. The costs are not dollars. The dollars are the least of it. There's a lot of money wasted.

Pete Wilson: On that, we agree.

Milton Friedman: The dollars are the least of it. What the real costs is what is done to our judicial system, what is done to our civil rights, what is done to other countries. I want Pete Wilson to tell me how he can justify destroying Colombia because we cannot enforce our laws. If we can enforce our laws, our laws prohibit the consumption of illegal drugs. If we can enforce those, it would be no problem about Colombia. But, as it is, we have caused th--tens of thousands of deaths in Colombia and other Latin American countries. I think that prohibition of drugs is the most immoral program--immoral program that the United States has ever engaged in. It's destroyed civil rights at home and it's destroyed nations…

Peter Robinson: It's destroyed civil rights at home because of large numbers of Blacks and Hispanics and…

[Talking at same time]

Peter Robinson: …what do you mean by that?

Milton Friedman: No, no. It's destroyed civil rights at home for a very simple reason. If you take laws against murder or theft…

Peter Robinson: Right.

Milton Friedman: …there's a victim who has an interest in reporting it. So if somebody is--has a burglary, he calls the cops and the cops come and investigate. Now in drug use, in the--when you try to prevent somebody from ingesting something he wants to ingest, you have a willing buyer and a willing seller. There's a deal made.

Peter Robinson: No one has an interest in reporting it.

Milton Friedman: No one has an interest--and so the only way you can enforce it is through informers. That's the way in which the Soviet Union tried to enforce similar la--laws, laws which tried to prevent people from saying things they shouldn't say. Th--what's the difference, Pete, between s--p--saying to somebody, the government may tell you what you can take in your mouth but the government may not tell you what you may say out of your mouth? Where's the difference?

Pete Wilson: The answer to your question is that they--they also enforce speed limits. I might like to drive a hundred and twenty miles an hour in a sixty-five mile zone but society tells me I can't. Why? What is their justification for curbing my free will? They are protecting others in society from the harm that I would do. When you say victims, drug use is hardly victimless whether it is legal or illegal.

Milton Friedman: I agree with you on that. It's not…

Pete Wilson: It's a tragedy. And it costs--where we do agree is that the dollars are the least of it. It is the incalculable human suffering, the waste of human potential and opportunity. It's the crack babies. It is…

Milton Friedman: But all of those are made worse by the attempt to prohibit it. And look, take marijuana, for example, in thousands of years, there's not been a single death from overuse of marijuana. There's not evidence whatsoever that marijuana causes people to harm other people. And yet--and six--what is it, six states now…

Pete Wilson: There's extraordinary evidence that PCP, methamphetamines and other dangerous drugs do.

Milton Friedman: Yes, and those drugs…

Pete Wilson: No question about it.

Milton Friedman: …those drugs are--have been stimulated and--and their--their market expanded by the tempt--attempt to prohibit other drugs which has driven up the price of drugs that are less harmful.

Peter Robinson: Can I--let me attempt…

Peter Robinson: Next topic, is it useful to treat hard and soft drugs differently?

Title: The Harder They Come

Peter Robinson: Pete, would you then be willing to decriminalize or at least entertain the decriminalization of marijuana and to draw a distinction between soft drugs, so to speak, of which marijuana would be the primary example and the harder drugs, heroin, co--cocaine, PCP's, methamphetamines. Would you be willing to entertain that?

Pete Wilson: I don't think it's a good idea to legalize either one but, of course, I would make that distinction because law enforcement makes the distinction and indeed the law presently makes that distinction. But one of the popular mythologies is that there are people in prison for simple possession of marijuana. If you talk to judges, if you talk to prosecutors, talk to prosecutors in particular, they will tell you that the people in the California prison system, at least, who are there because of drug convictions, are not there because of simple possession. They had copped a plea. They had engaged in plea bargaining. They are there because they are dealers.

Milton Friedman: Well many more there are dealers but, again, take the case of dealers. Because of prohibition, the dealer--the--the real dealers, have found it advantageous to hire teenagers because the juvenile laws punish them less s--less…

Peter Robinson: Less severely.

Milton Friedman: …less severely. When Rockefeller, Nelson Rockefeller was governor of New York, he put in especially stringent laws on drugs. But the juveniles were…

Peter Robinson: Exempted.

Milton Friedman: …exempted or--or on a lower level. And, as a result, the drug dealers st--switched to using juvenile. The attempt to prohibit drugs is one of the main reasons for the destruction of the ghettos in our cities. I'm sure you agree with that, Pete, that if you take--if you go into the ghettos, the prohibition of drugs is one of the main reasons why the prisoners in prison are disproportionately Black.

Pete Wilson: Well I--I think this is a separate issue. I really do because what you're saying is an indictment that is leveled by civil libertarians with respect to the criminal justice system in general.

Milton Friedman: Yes, it is.

Pete Wilson: And the answer is, the criminal law ought to be enforced in a way that it's totally color blind. If it's not, it should be.

Milton Friedman: But it's not because--it's not because the civil law is not col--color blind. It's because the ghettos are a good place to distribute drugs for obvious reasons. That's where you'll have a group that'll protect themselves, that'll provide protection. The customers are not Black for the most part. They come in from the outside, shop in the--in the inner cities.

Peter Robinson: So you have a relatively lawless environment where the serious dealers can set up shop, employ gangs and kids and it becomes a distribution center for the White people from the suburbs.

Milton Friedman: Absolutely.

Peter Robinson: That's roughly--could we engage…

Peter Robinson: A crucial question, would legalization cause drug consumption to go up?

Title: Up in Smoke

Peter Robinson: James Q. Wilson, quote, "The central problem with legalizing drugs is that it will increase drug consumption under almost any reasonable guess as to what the legalization regime would look like." Wilson then goes on to survey the literature. He finds the predictions about how much under a regime of legalization the price of hard drugs would drop, range from a factor of three to a factor of twenty. I quote again, "Now take a powerfully addictive substance, one that not only operates on but modifies the brain and ask how many more people would use it if its cash price were only thirty percent or even five percent of its current price. The answer must be a lot."

Milton Friedman: Well we have a good deal of evidence to counter Jim Wilson. In the first place, remember that drugs of all kinds were perfectly legal in the United States before 1914 or '13 rather. At that time…

Peter Robinson: The original Coca-Cola actually contained a trace of cocaine…

Milton Friedman: …it contained cocaine.

Peter Robinson: Right.

Milton Friedman: You could buy it. There were--there--there--and the--the level of drug addiction, by the best of estimates, was roughly the same as it is now. We have the experience now in Holland where essentially marijuana has dec--is de--dereg--is legalized or effectively legalized. And the rate of use of marijuana among tee--teenagers, among you--youngsters in Holland is less than it is in the United States. There are all sorts of things that Jim Wilson leaves out of that account. But for--but for the moment…

Peter Robinson: Right.

Milton Friedman: …let me suppose that there were--I'm not saying there would not be more users. There might be.

Peter Robinson: But isn't that the central point?

Milton Friedman: The people that might benefit most from legalization…

Pete Wilson: Yes, it is the central point.

Milton Friedman: …the people that would benefit most from legalization…

Peter Robinson: Right.

Milton Friedman: …are the addicts because they would have--have an assurance of quality. They would not be in danger of their lives. They wouldn't have to become criminals in order to support their habit. It would be a wholly different world for them. Right now, you speak about crack babies. Right now, women who are--pregnant women are afraid--who--who are drug users, are afraid to get an--a prenatal care, afraid to get care because they'll be called criminals and turned over to the justice system.

Peter Robinson: Let me go back to the other Wilson, James Q. Wilson. I quote Wilson, "John Stuart Mill, the father of modern libertarians," I go now to the moral point, "argued that society can only exert power over its members in order to prevent harm to others. I, James Q. Wilson, think the harm to others from drug illegalization will be greater than the harm and it is a great harm, it will be greater than the harm that now exists from keeping these drugs illegal." So it is a moral duty of the government to do what it can to contain the problem.

Milton Friedman: Well I think it's a whole new speech, this argument, because the--the argument for drug prohibition has always been, in terms of the interest of the drug users themselves, to prevent people from becoming drug users.

Peter Robinson: Right.

Milton Friedman: And so far as John Stuart Mills' dictum is concerned, he says government may never interfere for the benefit of the s--of the people who are using it or making the decision themselves. Only for the harm done to third parties.

Peter Robinson: You may victimize yourself if you wish to and the govern--that is not the government's business.

Milton Friedman: That's not the government's business. That's your business. You belong to yourself.

Pete Wilson: He is concerned about the user. I am far more concerned about the users' parents, about the users' child, that addicted crack baby, about all the people who are indeed the victims of the use of dangerous drugs, whether it is legalized or whether it remains illegal. And Jim Wilson is right, that really is the issue. How do you restrict the number of people who will become users and thereby minimize the tragedy.

Peter Robinson: What kind of arguments are Milton and Pete making, moral or utilitarian?

Title: Moral High Ground

Peter Robinson: It sounded to me a moment ago as though we were slip-sliding from John Stuart Mill in the direction of Jeremy Bentham in the greatest good for the greater number. Is it, to both of you, merely an economic question which ought, in principle, to be open to investigation.

Pete Wilson: Neither of us is it…

Peter Robinson: That is to say…

Pete Wilson: …primarily an economic question.

Peter Robinson: …if we're simply trying to say, under one regime, we have more drug users and, under the other regime, we have fewer drug users, whichever regime produces the fewer drug users is what we'll go for. That is not the case?

Milton Friedman: Of course not because you have to take account of the other harm which is done in the process of trying to prohibit the use of drugs. Look, alcohol kills a lot more people than--than drugs do.

Peter Robinson: But you're nevertheless making util--utilitarian rather than a moral argument. Drug use is wrong and it is…

Milton Friedman: I want to make…

Peter Robinson: …the responsibility to the government to embody moral values. You have none of that. You're not interested in that?

Milton Friedman: Yes I am.

Peter Robinson: You are?

Milton Friedman: I personally…

Peter Robinson: Right.

Milton Friedman: …am opposed to drug prohibition on moral grounds. I think it's unethical. I think it's immoral. However…

Peter Robinson: Right.

Milton Friedman: …lots of people don't agree with that and therefore, as an--as a person who is looking at the argument and trying to make the argument, I have gone and said, let's suppose I didn't have that view. What would my attitude be then? And I say, even then, as I look at the costs on the one hand and the benefits on the other, I say that the benefits for--the benefits from drug prohibition, even to those people who bel--believe it's moral, are far less in the costs, that this is a--it's--the drug prohibition has been a failure. We've had thirty years to try it. We've spent tens of hundreds of millions of people, we've sacrificed the lives of tens of thousands of people in this country and in other countries…

Peter Robinson: At the same…

Milton Friedman: …and what have we achieved?

Peter Robinson: …the same could be…

Milton Friedman: Nothing.

Peter Robinson: …said…

Pete Wilson: No, that isn't true either…

Peter Robinson: …in thirty or forty years, the same could be…

Pete Wilson: …in fact, your evidence is very selective.

Peter Robinson: …said of our approach toward the Soviet Union. We at least contained it. We had to live with it but we at least contained it. And that, in itself, is a moral and indeed a practical victory. Right?

Milton Friedman: Not…

Pete Wilson: Absolutely.

Milton Friedman: …it's not clear that we've--we haven't contained it.

Pete Wilson: But now, wait a minute.

Peter Robinson: Okay. Pete.

Pete Wilson: Let me give you some statistics that proves that we did when we were making the effort to do so. From '85 to '92, the estimated use of cocaine fell from 5.8 million Americans to 1.3. Now that's a significant figure. And I'm not going to drown you with other statistics because I think that one makes the point.

Peter Robinson: Let me make you drug czar for a year. How would you prosecute the war on drugs if you could reform it in any way you chose to do, what ways would you reform it?

Pete Wilson: I would do everything that could both reduce demand and reduce supply…

Peter Robinson: Let me ask…

Pete Wilson: …reduce availability and the last thing in the world that will reduce availability and reduce supply is to make it legal.

Peter Robinson: Okay, federal money…

Pete Wilson: There's no question. I mean, I would ask--I would ask Milton, what happened to the consumption of alcohol when there was a repeal of prohibition?

Milton Friedman: First of all, when--when there was a repeal of prohibition…

Pete Wilson: Did the end--did the use increase?

Milton Friedman: Initially it did but then it started going down again. It was a temporary increase. It's not at all clear that prohibition reduced the consumption of alcohol. And what is clear is that alcohol it pro--prohibition destroyed civil rights. It's clear that it also led to adulteration, that it led to a higher level of deaths. If you look at the different question, if you look at deaths and the use of alcohol, they rose during…

Peter Robinson: During prohibition.

Milton Friedman: …during prohibition.

Pete Wilson: But the paramount question is, if you are talking about a substance that produces tragic results…

Milton Friedman: That's alcohol.

Pete Wilson: It is also dangerous drugs far more than alcohol.

Milton Friedman: Not at all.

Pete Wilson: Well we…

Milton Friedman: …alcohol…

Pete Wilson: …we differ on that as well.

Milton Friedman: Well look at the rate of use…

Pete Wilson: I'm not here to…

Peter Robinson: If you're going to have a war on drugs, should drug treatment be given a higher priority?

Title: Trip or Treat?

Peter Robinson: Nineteen billion dollars slated in 2001 for the federal government--federal war on drugs. Another twenty-two billion among the states. It is certainly in the federal government and, by and large, true among the states, that the large share, the large majority of that money is devoted to law enforcement and interdiction efforts and only a relatively small minority of that money goes to drug treatment. Rand Corporation discovers in a study, treatment is seven times more cost effective than law enforcement, ten times more effective than drug interdiction and twenty-three times more cost effective than trying to cut drugs off at their source in Colombia or elsewhere in Latin America. Would you, as drug czar, shift resources away from interdiction and law enforcement to treatment?

Pete Wilson: I would fully fund treatment but what I would point out to Rand and anyone else who wants to argue the point, that most of the people who undergo treatment do not do so voluntarily.

Peter Robinson: That is true that--this...

Pete Wilson: It is under coercion and if it is illegal, they are under the coercion of the courts. That's how most of them get there. If you make it legal, do you want to take on the ACLU when they say, how can you compel my client to go to court or go to drug rehabilitation…

Milton Friedman: I'm not going to try to compel them. I would not…

Pete Wilson: Well and--and you know what, the result is there would be far less in terms of a percentage and probably even in absolute numbers, people going into treatment, if you legalize it than if you maintain its illegality.

Peter Robinson: Let's just grant that, as a political matter, for a number of reasons, a war on drugs, a major and sustained effort against drug use is just going to be with us. Let's just stipulate that it will. The question then would be, would you favor granting the government the coercive power to force people into treatment? Would you favor a massive shifting of resources from drug enforcement and drug interdiction to treatment?

Milton Friedman: Yes I would.

Peter Robinson: As a matter of principle, would you favor treating the war on drugs less as a matter of law enforcement…

Pete Wilson: I would do both, Peter.

Peter Robinson: …and more as…you would do more?

Pete Wilson: I would do both because--and that's what happened during the period…

Milton Friedman: That's what they've been saying all these years…

Pete Wilson: …that we made significant progress on containment. Now we're never going to achieve perfection or anything close to it but what I will tell you is that it made an enormous difference. Fifty-eight or 5.8 million to 1.3 million in a seven year period is a very significant drop.

Peter Robinson: Even that came at too high a cost in your view?

Milton Friedman: Oh yes it did but moreover, it's very misleading. If you look over history at--at periods of dr--you have periods when drugs go up, periods when drugs go down. Without making things illegal, things can also be affected. Look at what's happened in--in smoking. Tobacco kills far more people than--than drugs do by--by a multiple. By information, by knowledge, you've had a strong reduction in--in--in smoking.

Peter Robinson: So under the Milton Friedman…

Peter Robinson: If drugs were legalized, would anti-drug campaigns still be effective?

Title: Smoke 'em If You Got 'em

Peter Robinson: So under the Milton Friedman regime, that would not be a regime of moral laxity, it would be a regime of--under which drug use was legal but that would--you would--you, yourself would sign up to join the anti-drug temperate society. You would want large organizations, probably voluntary in your view, to be advertising against drugs, to be speaking against drugs…

Milton Friedman: Absolutely.

Peter Robinson: …you would want public pressure exerted on people to persuade them not to use drugs.

Milton Friedman: I think drugs are terrible. I think people ought not to use drugs. I think it's not in their self-interest to use drugs. But if people insist on doing things in their self-interest, who am I to stop them? What I have to do is to stop them from doing harm to other people. That's the function of government as Pete and I agree. But I could do more--far more effectively, stop them from doing harm to other people in a legalized regime than I can in a--in a regime in which so-called illegal drugs are illeg--are--are--are illegal.

Pete Wilson: Well I think history contradicts that. He mentioned the Dutch experience. The Dutch experience has not been a great success. If you look at the U.S. Department of Justice studies, the highest per capita crime rate to be found anywhere in Europe is in Amsterdam. If you look at the British experience, when they legalized it, allowing physicians to prescribe heroin, they experienced a thirty-fold increase in heroin use. And that wasn't all of the use either. You asked a question a moment ago, Milton answered it, I didn't. You said, is the basic point that we contain use? And the answer is, absolutely. When Mr. Sterling, the Director of the National Criminal Justice Foundation was making his remarks at the Hoover Symposium in this past year, I believe, his concluding remark was that there is no question that the increased availability of drugs makes it far more difficult for teenagers to resist the temptation. Well I can't think of anything that will more greatly increase the availability of drugs than legalizing it.

Milton Friedman: What happens under the current circumstances is that teenage…

Peter Robinson: I have the last word. It's television so…

Milton Friedman: …teenagers tend to be attracted to drugs by--by the fact that they're illegal. First of all, there's propaganda against drugs which is so outrageous, which is so violent, violates what they know to be facts, when they're told that marijuana will eat out their brains, for example, that they come to distrust all such statements. And the, you know, the fact that it's illegal is an attraction, not a--a deterrent. In my opinion, there's no evidence whatsoever that legalizing drugs would cause any major increase in uses. I think you'll have periods when drug use goes up, periods when drug use goes down as you do with all other human phenomena. And I think that what you have to take into account is the enormous amount of harm that the attempt to prohibit drugs does to our system of laws, to our civil liberties, to human freedom and that we'll be more effective…

Peter Robinson: Pete Wilson, you've got about twenty seconds…

Milton Friedman: …in reducing the use of drugs…

Peter Robinson: …for a closing statement.

Milton Friedman: …by persuasion than by…

Pete Wilson: Drug use, legal or illegal, is a tragedy if we're talking about hard, dangerous drugs. Drugs are not bad because they are illegal. We made them illegal because they produce tragic results. And the cost in dollars is the least of it. The human cost in calculable tragedy, the parents, the crack babies, that is the tragedy and John Stuart Mill said that society has a right to protect the third parties from harm by those who would exercise their own will doing something stupid.

Peter Robinson: Pete Wilson, Milton Friedman, thank you very much.

Peter Robinson: Prohibition lasted only a dozen years before the Eighteenth Amendment was repealed. The war on drugs, the war on drugs has already lasted nearly three times as long. And as we just saw, the debate continues. I'm Peter Robinson. Thanks for joining us.