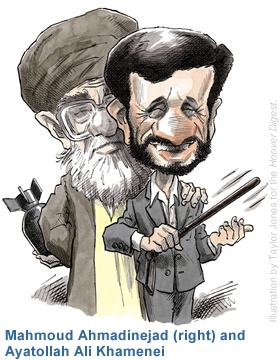

Iran’s presidential elections in June 2005 stunned the world. In the first round of elections, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a virtual unknown, won enough votes to make it to the second round. His rival in the runoff election was Akbar Rafsanjani, who had been one of the pillars of power in the regime since its inception. Against all odds, and contrary to many polls and predictions, Ahmadinejad won the runoff election, and thus began a new stage of the Islamic Republic.

The Ahmadinejad presidency represents a time of peril and promise, not just for the democratic movement in Iran but for the future of U.S. policy in that country and the greater Middle East.

A Winning Coalition

Ahmadinejad’s electoral victory is the latest stage in a grab for total power by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and a discordant cabal of allies. It was also a masterful lesson in how to “democratically” rig an election. Even though the list of presidential candidates had been vetted by the cabal and wiped clean of any person deemed undesirable, the cabal nevertheless felt compelled to interfere overtly in the election, particularly in the first round. Only in this way could it ensure the victory of Ahmadinejad—its stealth candidate—who was largely unknown by the masses, despite having been mayor of Tehran.

Along with Khamenei, Iran’s “Spiritual Leader,” the leading members of the cabal include a few conservative clergy, several Revolutionary Guard commanders, and a handful of political figures such as Hadad Adel, now Speaker of the parliament, and Khamenei’s son, Mojtaba.

The financial muscle—aside from the tens of millions of dollars of government funds used illicitly in favor of Ahmadinejad—was provided by segments of the bazaar (the hub of commerce and finance in Iran for centuries) connected to the shady right-wing group called Hojatiyye, which emerged during the reign of the Shah and avoided politics, concentrating instead on fighting the growth of the Bahai religion. (The Bahai faith grew out of the teachings of Mohammad Ali Bab, who made his claim of prophecy in mid-nineteenth-century Iran. From the moment of its inception, the growth of the faith was ferociously opposed by the Shiite clerics, who denigrated the faith not just as heresy but as a foreign colonialist concoction.) Today, much to the consternation of the old-guard mullahs who risked life and limb engaging in radical politics under the reign of the Shah, Hojatiyye has become one of the most powerful groups in Iran. It is led by Ayatollah Mesbah, a hard-line fundamentalist who runs the Haggani school, where the most strident version of Shiism, defiantly anti-democratic and anti-Western, has been taught over the last two decades. Many members of Ahmadinejad’s inner circle are said to be Haggani graduates.

Another ally of the cabal has been the group called Motalefe, which is rooted in an old Islamic terrorist organization and has in recent years also been connected to the bazaar. The group’s members have enriched themselves in the last two decades by dominating the retail and distribution networks in Iran and by receiving lucrative “special” permits and import licenses given to them as patronage by the state.

In sheer numbers, the most important part of the coalition was made up of millions of the youthful paramilitarists known as basijis. In political morphology and methods, they are a cross between a conglomerate of neighborhood gangs and a vast network of ideologically inspired militia groups. For the last decade, they have provided Ayatollah Khamenei with the necessary power to suppress the opposition and contain any street demonstrations. Along with the Revolutionary Guards, the basijis were ordered to go to the polls and vote for Ahmadinejad—and to each take along 10 family members! Thousands of them had also been hired as “poll watchers” and “trained” for months before the election. They were promised that, in an Ahmadinejad presidency, there would be a Basji Ministry and that all members would become government employees—a coveted prize, given the massive unemployment in Iran. (As of early December, four months into the administration, none of these promises have been fulfilled.)

The concentrated work of all these groups in the first round of the elections guaranteed that Ahmadinejad was one of the two candidates headed for the second (runoff) round.

In the runoff election, this discordant coalition succeeded in attracting substantial segments of the disenfranchised poor with a populist message that promised to end crony capitalism and shrink the gap between rich and poor. In fact, economic issues—from unemployment to inequality to corruption—were the dominant themes of the election. The cabal was helped by the failure of outgoing president Khatami and his reform movement to deliver on their political promises and improve Iran’s dire economy. Those failures were compounded by the inability of the reformists to agree on a single candidate or to form a tight, responsive, and nimble political organization. In the runoff, the reform movement was forced to support Rafsanjani—a figure much despised in Iran for his alleged financial corruption and political arrogance. Rafsanjani’s candidacy ensured another defeat for the forces advocating reform and democracy.

Disarray in Tehran

The Ahmadinejad administration is already notorious—even in the eyes of some of the Islamic regime’s stalwart supporters—for its mediocrity and for its domination by Iran’s military and intelligence forces.

The presidential election, and the grab for complete power by Ayatollah Khamenei, has left in its wake a growing rift in the ranks of the hitherto unified clerical hierarchy. More than four months after the election, the various factions had yet to agree on appointments to head four of the most important ministries: oil, education, social welfare, and cooperatives. Finally, in late November, Ahmadinejad submitted four new names as candidates for these ministries. Three of his candidates received enough votes for confirmation, barely. But his attempt to fill the oil ministry failed again. The proposed minister withdrew his name from consideration when members of the parliament threatened to look into his apparently ill-gotten millions of dollars. A third candidate was submitted, but he too failed to receive the required vote of confidence from the parliament. As of early December, the crucial oil ministry remains vacant.

Despite Iran’s unprecedented oil revenues, the Iranian economy is in trouble. Millions live in poverty, and millions of others (particularly young people) are chronically unemployed. The new president’s populist and vacuous pronouncements on the economy have led to a surprising economic slump. The state already accounts for about 80 percent of the Iranian economy, yet Ahmadinejad has promised to further strengthen the public sector. Private sector investments have all but completely stopped. Private banking is in a severe crisis: the president has indicated that banks should be a monopoly of the government, and thus the government has been lowering interest rates. In fact, there are rumors that the government intends to outlaw interest altogether (because Islam bars usury), and many bank managers have announced a moratorium on all lending. The stock market collapsed when word got out that the president-elect had opined that the stock market is a form of gambling and thus “un-Islamic.” As of early October 2005, estimates are that the stock market had lost a staggering one-third of its total value since the election. To bring back some security to the badly shaken markets, the regime in recent weeks has been pressuring mullahs and their madrassas to purchase stocks publicly. But these efforts have so far been for naught. According to government sources, since the election there has been a massive flight of financial capital from Iran, and thousands of companies owned by Iranians are operating in Dubai and elsewhere outside Iran. Even the usually robust real estate market in Tehran is eerily inactive. It is estimated that more than $200 billion has already left Iran.

Furthermore, many of Iran’s best and brightest have left the country, making Iran number one in the world in terms of brain drain, according to a recent International Monetary Fund survey.

On the international scene, many in the regime now feel that Iran is becoming dangerously isolated and vulnerable. In recent years the regime has often rightfully congratulated itself on its ability to pit the European Union against the United States, Russia against the West, and China and India—who together have signed agreements to purchase Iran’s oil to the tune of $150 billion—against everyone else. But the European Union no longer seems willing to be used as a foil against the United States; India has shown little willingness to endanger its ties with Europe and the United States over Iran; and thus the Islamic regime is now seriously stymied in its ability to play countries against one another. The adventurism of the regime, or its allies, in southern Iraq, and increasing evidence that it has provided Sunni terrorists with sophisticated, armor-piercing bombs, has put Iran on a collision course with England. Iran has openly accused England of complicity in recent bombings in the oil-rich southern provinces of Iran.

Playing with Nukes: A Dangerous Game

This combination of internal and external disarray has led to a chorus of voices, including pillars of the regime such as Rafsanjani, who are blaming the country’s troubles on the inexperience and radicalism of the new administration. Some of these voices, like those of the Islamic Revolutionary Organization and some members of the parliament, have insisted on the right of Iran to a peaceful nuclear program, but even they are now questioning the wisdom of pursuing it at the cost of becoming a pariah nation. The fact that these voices have emerged despite the secretive nature of the inner corridors of power in Iran, and despite increasing censorship in the media, indicates that greater opposition to current policies may well exist behind closed doors. In the past, the regime rallied support for its policy by telling the Iranian people—and those in the Third World who had a stake in the debate—that the Islamic Republic was standing up for Iran’s right to have a nuclear program. It successfully fanned the flames of nationalism and of injured pride. As it is becoming more and more evident that the regime’s pursuit of the bomb has only political self-preservation as its goal, popular support for the policy is also dissipating.

The clerical cabal that won the election is pushing the captive Iranian people ever closer to a precipice, whereon the country will stand alone and face the wrath of the global community. In early October, in an effort to calm the jittery markets at home and the anxious capitals around the world, the Islamic Republic announced that henceforth strategic policies will be in the hands of the “Expediency Council”—in other words not in the obviously incapable hands of Ahmadinejad. But this has done little to improve the situation. The regime’s only hope is that China’s insatiable appetite for energy will convince it to use its veto power to thwart possible U.N. sanctions.

The regime and its apologists, as well as some independent observers, have claimed that there is in Iran a consensus, indeed nothing short of a nationalist fervor, in favor of a nuclear program. Any pressure on the regime, they say, will strengthen its position in the midst of the otherwise alienated and disgruntled population. A “grand bargain” with the mullahs, giving them U.S. security assurances in return for Iran’s promise to give up its nuclear ambitions, is, according to these merchants of compromise, the only option open to the United States.

Another camp has come to an entirely different conclusion. Only surgical attacks on the regime’s nuclear facilities, they say, can solve the question of the Islamic Republic’s nuclear ambitions. This group overlooks the fact that any attack on Iran has dubious legal foundations and is sure to kill hundreds of innocent Iranians. Furthermore, an attack will likely do no damage to the deeply fortified nuclear centers and is sure to consolidate the power of the most dangerous elements of the regime.

In fact, the only answer to Iran’s nuclear problem is democracy. At this particular junction, the solution (maybe counterintuitively) is neither war nor a deal with the regime but instead a grand alliance with the predominantly pro-American Iranian people. Events in the last few months have shown that popular support for the nuclear program is surprisingly ephemeral and contingent and that the crisis of leadership is deepening in Iran.

The West, particularly the United States, inadvertently helped the clerics in their effort to camouflage the real intent of the nuclear program by failing to engage with the Iranian people about the real issues underlying the problem. Questions about the real economic costs and viability of a nuclear program, debates about the real strategic value and cost of a nuclear bomb for Iran, and discussions on the urgent issue of nuclear safety were never part of a credible U.S. or E.U. attempt to engage the Iranian people. But the recent developments in Iran have created a new landscape and new opportunities for the United States actively to engage in this debate.

Instead of saber rattling, the United States must encourage the unfolding discussions in Iran. It must reassure the Iranian people that it respects their right to develop a nuclear program and that the problem is not with the people, but with those who have coercively monopolized the right to speak for them. Every element of this new grand bargain—for example, ending the embargo and replacing it with smart sanctions, immediately lifting the ban on airplane spare parts, offering earthquake warning systems to populated cities sitting on dangerous fault lines, and initiating direct and open discussions with the regime—must clearly be part of a grand strategy of helping the Iranian people achieve their hundred-year-old dream of democracy.

Ahmadinejad’s increasingly obvious eccentricities are likely to further isolate the regime and might help pave the road to democracy. His speech to the United Nations in September was a stark reminder of his incompetence—and the jarring gap between reality and his self-perception. The speech, in which he attacked the West, particularly the United States and Israel, was all but universally dismissed as an empty compendium of dangerous slogans. (No less universally condemned was his speech a few weeks later when he called for the annihilation of the state of Israel.) But in Ahmadinejad’s mind, the U.N. speech was nothing short of divine intervention. In a recently released video of a courtesy call to one of Iran’s religious leaders—Ayatollah Amoli—Ahmadinejad claims that when he was talking at the United Nations, a halo suddenly appeared around his head. He goes on to claim that a protective cocoon surrounded him and that his audience was so mesmerized by the sight of his halo that not a single eyelash moved. Of course, no one saw a halo, and, if they were mesmerized, it was by the egregious nature of his claims.

The shocking incompetence of the new regime might open just enough of a gap in Iran’s pseudo-totalitarian power structure so that the indigenous forces of democracy can thrive again. Wise and judicious U.S. policy can help widen that gap, reinvigorating the dormant movement for democracy in Iran.