Whether Iran succeeds in gaining legitimacy with Europe and the United States after the end of sanctions by the West may have less to do with choices by the Western countries and more to do with internal Iranian politics. All of the parties to the Iranian nuclear deal want to provide that legitimacy; but Iran’s opaque internecine politics may get in the way.

European companies are already frothing to take up opportunities in Iran. Sanctions on Russia for its invasion of Ukraine and retaliatory sanctions by Russia on European countries have pinched European businesses, especially those of Germany, Italy, and Greece. Russia provided export markets and imports of energy, both of which are in short supply in a Europe still wracked by the near default of Greece. So Iran will be a welcome outlet for entrepreneurs and a fresh supply of oil and gas.

American companies are much less likely to be interested in investments or business relationships in Iran than are our European counterparts. Partly because Europeans have not had as fraught a history with Iran as has the U.S., and partly because Congress could well act to frustrate the President’s intention by legislative means. American companies are much more concerned about being netted dealing with Iran, or Treasury concerns requiring an expensive disentanglement. President Obama may seek to encourage economic links as a legacy issue or to accelerate western investment past Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps companies and reach a wider pool of Iranian beneficiaries.

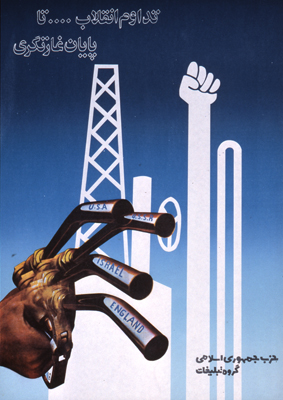

But neither European commercial lust nor American aspirations for diplomatic thaw with Iran are likely to be adequate to pull Iran toward state legitimacy. Iran’s continuing support for terrorist organizations like Hezbollah, efforts to destabilize Sunni governments in Bahrain, Yemen, and Lebanon, alliance with Bashar al-Assad’s murderous government in Syria, predatory behavior in Iraq, threats to Israel, and aggressive ballistic missile tests (the most recent was just after the nuclear agreement came into force last October) all provide continuing reasons for skepticism that Iran will shed being a revolutionary movement in order to be a state viewed as legitimate in the eyes of the West.

Perhaps even more significant is the internal friction over Iran’s direction. There appears to be an ongoing power struggle between the political establishment (which includes the religious leadership and a heavy component of Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps veterans) that would sustain Iran’s current policies, and a widespread desire among urban Iranians for more permissive social policies, less political repression, and more economic opportunity.

Iran is a difficult country for America to gauge. We have not had diplomatic representation in Tehran or commercial relations with any Iranian entity since the 1979 revolution. Both governments’ attitudes are colored by the hostility of the American-backed coup against Iranian Prime Minister Mossadegh in 1953 and the Iranian seizure of American hostages in 1979. The Iranian government is opaque, power unconstrained by either institutions or the transparency of a free press. Much of what we do know is filtered through the eyes and experiences of Iranian émigrés in America: the second largest Iranian city is not Isfahan or Shiraz, it is Los Angeles. So the starting point for determining Iranian government behavior is a recognition that we know very little about what is actually occurring within the leadership.

We do know a few things, however. Since the 1979 revolution, Iran has been governed by a fusion of political and religious power (a system known as Vilayat-e Faqih). The Supreme Leader is just as described: supreme. Real decision-making power resides not in the elected legislature, but in a Guardian Council of the Supreme Leader’s choosing with the power to overrule the legislature, interpret the Constitution, and approve candidates for public office.

It is a conceptual mistake to talk of Iranian “moderates” in the leadership. Those Iranians entrusted with power are beholden to the Supreme Leader and have been carefully vetted. The actual reformists are in jail or under house arrest since the 2009 election. It is illegal to even display a photograph of an earlier reformist president, Mohammad Khatami—which is both an indicator of how repressive Iran’s government is and how frightened it is about the public’s desire not to continue being suffocated by that repression.

It is Iranian practice to hold frequent elections to create a patina of legitimacy, yet prevent real democracy by tightly controlling who can run for office. In the most recent Parliamentary elections, the Guardian Council refused more than 6,000 prospective candidates. Of reformist candidates, only 30 of 3,000 were permitted on the ballot.

Iranians are dissatisfied with their government. Protests that erupted after 2009’s disputed election were put down by force, thousands of activists were arrested, and Iran’s religious leadership seemed to vacillate about whether to support the Supreme Leader acting so obviously in opposition to popular will. The favored establishment candidate in 2013 elections was trounced. Current President Hassan Rouhani campaigned on releasing political prisoners and moderating government intrusion into civil society; no such policies have been enacted.

But many Iranians also believe the system can change—otherwise they would not seek to run for office. Remnants of the reform movement also shifted strategy this election, knowing the vast majority of reform-minded candidates would be stricken off the ballot. They recruited young candidates who are not necessarily reformists to displace known hard-liners. Iranian voters, as they had in 2009 and 2014, voted for the most moderate candidates on the ballot.

Iran is on the brink of an epochal transfer of power. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is old and ailing. An Assembly of Experts selected to determine Khamenei’s successor are decidedly less strident than the electors they are replacing. But whether Iran’s political and economic elite permit themselves to be eased out is an open question.

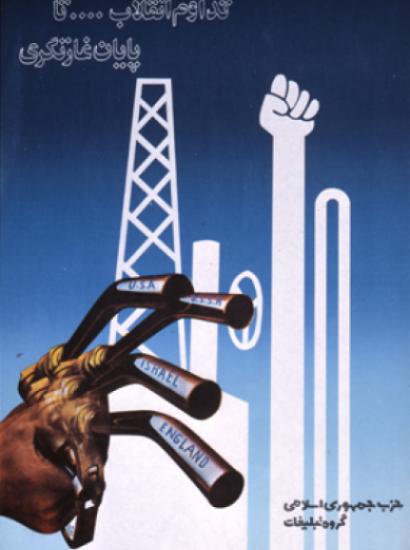

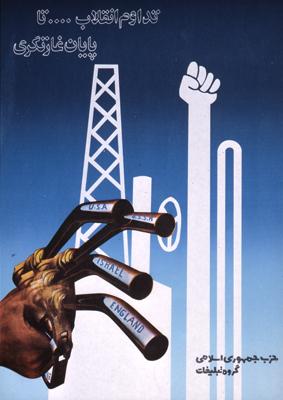

Iran’s economy desperately needs infusions of investment and technology—in 1978 Iran’s oilfields pumped 5.4 million barrels of oil per day; now they can produce only 2.8 million. Sanctions over Iran’s nuclear program and the plummeting price of oil both aggravate (and to some extent mask) the Iranian government’s economic mismanagement. But the political and economic openness on which that investment depends is anathema to many in Iran’s ruling elite ideologically and also a threat to their preferential economic opportunities.

The Rouhani government seems to be emulating China’s approach of attempting to forestall political change with prosperity. Nearly all his policy efforts have focused on ending Western sanctions and encouraging foreign investment. The Iran nuclear deal has unfrozen $10 billion of Iranian assets and allowed oil exports to resume. Whether Iran’s government is fleet enough to outrun its citizens aspirations will likely determine whether Iran remains a revolutionary power or gains the state legitimacy on offer from the West.