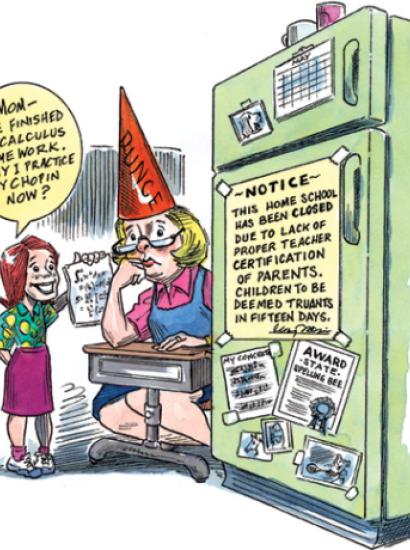

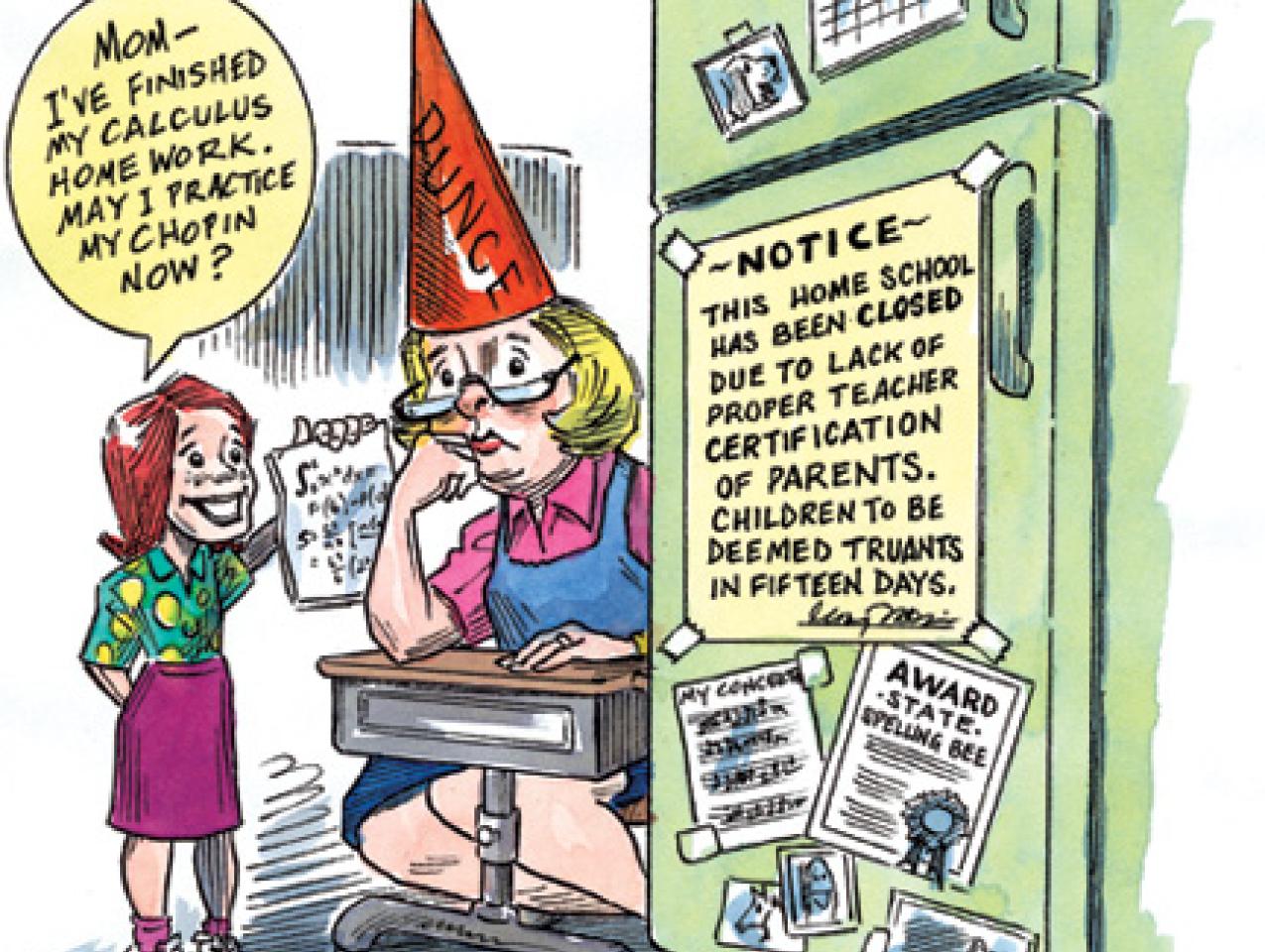

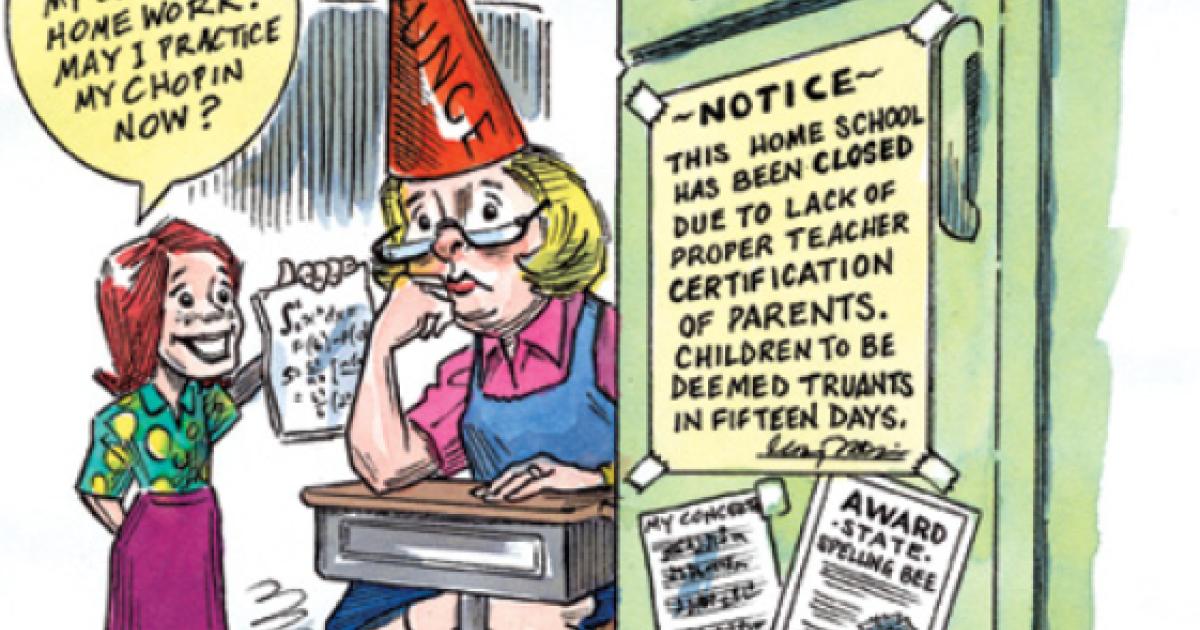

A. J. Duffy, president of United Teachers Los Angeles, tells us that California’s Second District Court of Appeal was correct to rule in February that parents without teaching credentials cannot educate their children at home —that is to say, most of the 166,000-odd homeschooled students in the Golden State could be truants and their parents may be violating the law.

Duffy missed a fine opportunity to keep quiet when he said, “What’s best for a child is to be taught by a credentialed teacher.” This echoes other union honchos and even former California Superintendent for Public Instruction Delaine Eastin, who wrote in 2002 that all schooling in her state needed to be supervised by professionally trained teachers. Furthermore, Eastin noted, “Home schools are not even subject to competition from private schools, where the marketplace would presumably ensure some level of quality and innovation. ”

Such statements are risible. The Los Angeles Unified School District enrolls some 700,000 students taught by the credentialed teachers that Duffy represents; a mere 33 percent of those pupils are proficient in reading, only 38 percent make the grade in math, and only 44 percent ever graduate. What ’s best for a child, it seems, has little or nothing to do with the credentials Duffy cherishes.

Furthermore, it is particularly noxious for the head of a big-city teachers’ union, the members of which are failing to educate a stunning number of their pupils, to cheer a court decision that denies the competence of parent educators. Duffy —whose motivations for pushing more students into Los Angeles’s classrooms may be laudable, but may also stem from a desire to swell the ranks of public school students to force the district to hire more dues-paying teachers —ought not lecture parents about “what’s best” for their own children.

Eastin’s ideas are less distasteful than Duffy’s but just as brazen. To complain that home schools are not “subject to competition” is not only wrong, but also quite rich coming from a former higher-up of a state-run, public school bureaucracy that actively tries to eliminate competition that might entice families away from it.

The specifics of the court case in question are these: the eldest of Phillip and Mary Long ’s eight children reported the father as physically and emotionally abusive. All eight children had hitherto been homeschooled. An attorney representing the two youngest siblings asked a juvenile court to order that they be enrolled in a public or private school where teachers could monitor them daily. The lower court declined to issue such an order, noting that California parents have a right to homeschool their children. The Second District Court of Appeal disagreed.

It found that People v. Turner (1953) mandated that California parents send their children to either a full-time private school or a full-time public school, or that they have them educated by a credentialed tutor. Turner, wrote Justice H. Walter Croskey in his decision for the appellate court, “specifically rejected the argument that it is unconstitutional to require that parents possess the [teaching] qualifications prescribed by statute. ”

California law does not require that private school teachers possess such qualifications, however —only that they be “persons capable of teaching.” Turner acknowledges no contradiction here. Why not? Apparently it’s a question of oversight. It is unreasonable for the state to monitor individual parents who homeschool their children, Turner maintains, but far less so for it to monitor private school instruction. This logic suggests that California ’s government surveils—or, at least, that it could surveil—its multitude of private schools, which the state neither does nor could ever hope to do. But no matter.

According to Turner, private school teachers need not possess educational credentials because they will be overseen by managers who, motivated by the desire to run a successful school, will brook no incompetence from the teachers in their employ. Parents, one must presume from this reasoning, are less motivated to ensure that their own children receive a solid education than are anonymous private or public school principals. By affirming this goofy logic, Croskey upholds the thinking of Duffy —that parents are incapable of doing right by their kids.

Of course, the parents involved in the case at issue, Phillip and Mary Long, may well be incapable of doing right by their kids —indeed the evidence suggests that they are. This is an aberration, however, especially in the homeschooling community, which is reportedly a redoubt of parents who are so concerned about their children ’s well-being that they devote substantial time and energy to teaching class in their kitchens.

Some adults abuse their children. It’s awful, but it’s not a compelling argument for criminalizing homeschooling. Limiting parents’ ability to homeschool to combat child abuse is a crude solution for a more specific problem. It is also, perhaps, not much of a solution: the high rates of truancy in many public schools; the anonymity that can pervade some of the larger, more impersonal ones; and the migration of students among states and cities and classrooms render it possible that abusive parents may be just as abusive, for just as long, regardless of whether their child attends the local school or stays at home. Moreover, evidence suggests that students have a greater risk of being abused at school than at home —in fact, that’s precisely why many parents homeschool in the first place.

To force happily homeschooled pupils into public school classrooms simply to monitor potential abuse is a poor idea. And it will surely condemn sundry youngsters to a lesser education than they would have received from Mom and Dad. The purpose of public schools is to teach students, not to manage every facet of their lives (or their parents ’); nor is it the school’s responsibility to manage the well-being of its students. Such matters are beyond the scope of the purpose of schools, and schools are ill-equipped to handle such matters competently.

The appellate court’s findings may not be overturned. Californians currently have no explicit state or federal constitutional “right” to homeschool their children (such rights have usually been assumed to occupy various “penumbras” of constitutional language). Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger has vowed to push through legislation clarifying this muddle. Some thirty states have already done so, and California shouldn ’t hesitate to join them.