As the Rio Olympics reach their mid-way point, it is instructive to reflect on the ancient martial origins of the games and how they have been used throughout history to reflect the power of cities and states through the lens of champion athletes.

The Olympic Games began in Greece in 776 B.C., a festival dedicated to the god Zeus. For more than a millennium champion athletes from across the Greek world would gather together every four years at the western Peloponnesian sanctuary of Olympia to contest a variety of events: foot races, horse and chariot races, discus, shot put, standing long jump, boxing, pankration (the ancient equivalent of today’s ultimate fighting championship), and a race featuring men wearing hoplite armor. There was also the pentathlon, the ultimate test of strength and skill: discus, standing long jump, javelin, running, and wrestling. An Olympic truce would allow the games to be held even in times of war.

Perhaps the greatest ancient Olympian was Leonidas of Rhodes, who won the stadion (just under 200 meters, and the origin of our modern word stadium), diaulos (two stadia), and hoplite race at four consecutive Olympic games from 164 to 152 B.C. His record of a dozen individual victories was finally surpassed more than two millennia later at the Rio Olympics, when swimmer Michael Phelps won the 400 meter individual medley, his thirteenth individual victory in the Olympic Games. But Phelps didn’t have to swim three of his races in armor.

The ancient Olympics, however, were not just about sport; they were also about power and prestige. Most of the events had parallels to combat: the javelin replicated the throwing of spears against enemy ranks; the pankration, boxing, and wrestling were forms of hand-to-hand combat, horse and chariot races replicated the roles of cavalry on the battlefield, and the hoplite race mirrored the charge of a man in a phalanx.

Prizes for Olympic champions were olive leaf wreaths along with fame and fortune. Rewards for their native city-states were more abstract, but real nonetheless. The games became a means to showcase political dominance over rival city-states. The Olympiad became so important to Greek culture that ancient historians often dated events according to the Olympiad in which they occurred.

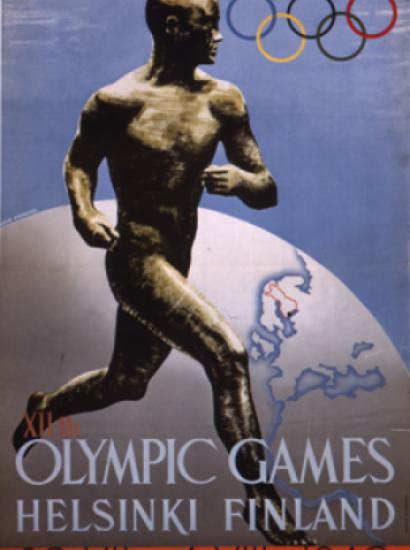

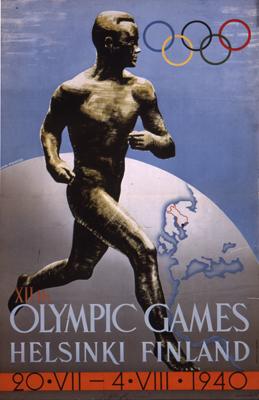

The rebirth of the modern Olympics in 1896 was hailed as a celebration of sport and the coming together of nations. The founder of the modern Olympic Games, Pierre de Coubertin, once said, “The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part; the essential thing in life is not conquering but fighting well.” If only.

The Olympics have sometimes lived up to the high ideals embodied in the “Olympic spirit,” but they have just as often been used for purposes of prestige and power, as they were in the ancient Greek world. Adolf Hitler intended the 1936 Berlin summer Olympics to showcase the glory of the Third Reich and the superiority of the Aryan athletes, a plan derailed by African-American Jesse Owens winning four gold medals in track and field. During the Cold War, Soviet and Eastern-bloc athletes were trained as professionals and sometimes given drugs (such as steroids) to improve their performances. In one of the most egregious cases of doping in the Cold War, the East German women’s swim team thoroughly dominated the 1976 Montreal Olympics due to their use of performance-enhancing drugs. Doping was not the product of individual athletes seeking an unfair advantage; this was a state seeking dominance on the international stage. Indeed, Olympic competitions during the Cold War can be seen as a substitute for warfare: the rejoicing of Americans over the victory of the U.S. men’s hockey team in the 1980 Lake Placid Winter Games was akin to the celebrations surrounding VE-Day.

The use of the Olympics for state purposes is alive and well today. Vladimir Putin’s Russia felt strongly enough about Olympic glory to engage in systematic use of performance enhancing drugs across a wide range of Olympic disciplines. The furor over this doping scandal has led to the banning of much of the Russian team, including the entire track and weight-lifting teams, from the Rio games. Americans love the final part of every prime-time Olympic broadcast, the medal count—a celebration not of individual prowess, the coming together of nations, and the importance of taking part, but of national reputation and glory. The ancient Greeks would be proud of their legacy.