As you read this, a ragged alliance of rival forces fights to wrest Mosul’s western half from the grip of the Islamic State. The besiegers represent different ethnic and religious factions jockeying for power in the ruins. The defenders are religious fanatics of an apocalyptic faith. Hundreds of thousands of civilians are captive in their midst.

We of the human race have been here before and will come here again. Cities, the emblem and apogee of all civilizations, have been war’s great prizes since the days of myth. Sieges—nowadays the least-studied form of military operations—have stained history with vast amounts of blood, from Carthage to Constantinople. And they’re back.

Sieges have always been brutal, exacerbated by plague, famine, and fratricide within the city walls. But when one or both sides have been armor-plated with ideology or faith, the last pretenses of civilization vanish. States and dynasties generally preferred to capture cities and their wealth-generating capacities intact. Ideologues and fanatics revel in death.

The Roman siege of Jerusalem in A.D. 70 was prototypical. The Zealots and other factions within the city’s walls resisted to the end and, as the situation within those walls deteriorated, Zealots killed more fellow Jews than they killed Romans. The last struggle was bitter and the Romans, in their turn, were merciless. Jerusalem had become more trouble than it was worth.

In the Great Mutiny, or First Indian War of Independence, of 1857, Hindus and Muslims initially allied against the British occupiers. But Wahhabi fanatics took over besieged Delhi, which the Hindu mutineers left in disgust. When the cholera-tormented British stormed through the Kashmir Gate and embarked on a vengeful slaughter, Islamist fanatics had already thinned the resistance.

From those and many other sieges, we’ve seen, time and again, how religious fanatics turn on their own less-devout coreligionists or rivals, from Muenster to Mosul. But ideological competitions, often between great powers, can be equally or even more destructive and uncompromising—because ideology-driven regimes possess more firepower. The defeat of the Paris Commune of 1871 involved German siege guns shelling a starving (and finally captive) population, followed by mass executions when the Commune fell. The Communards perished, but a new fanaticism was born.

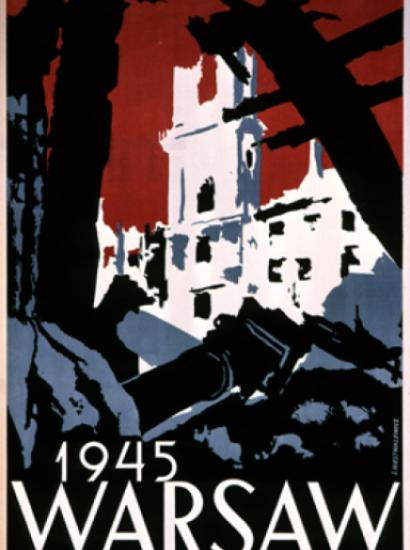

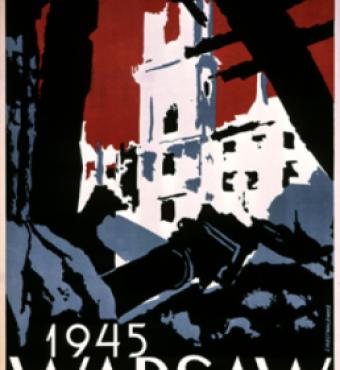

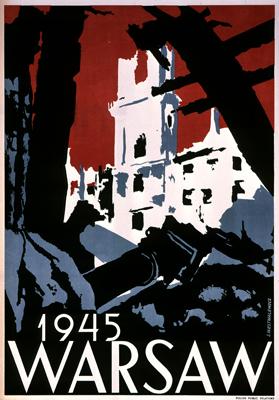

In Warsaw—that immeasurably heroic city—the Nazis didn’t just quell but annihilated the 1943 Ghetto Uprising. The following year, as two monstrous ideologies faced off across the Vistula River, the Polish Home Army rose, expecting the besieging Red Army to come to its aid. Instead, Stalin watched cynically as the Nazis defeated the uprising, destroying Warsaw in the process, and only moved on the city after the Germans had finished off the Poles.

Earlier in the war, the siege of Leningrad, another all-or-nothing struggle, created immense civilian suffering. The Second World War moved eastward then westward again from city to city—yet, military histories focus on sweeping maneuvers and armored duels.

That has been a general pattern: Students of military history naturally are drawn to the movement, color, and drama of field campaigns and battles on landscapes suited for terrain walks. The dynamic movements and obvious heroism are easier on the soul than the grinding cruelty, filth, and truth of sieges.

Yet, we are, again, in an age of urban warfare and the struggles for Fallujah, Ramadi, Aleppo, and dozens of smaller cities and towns where the local social contracts have collapsed. The horror of the last century’s ideological struggles that tormented Madrid and devastated Manila, that gutted Berlin and leveled Seoul, are being replayed with the amphetamine shock of religion injected into conflict’s arteries.

If you’re a romantic, study those swift, far-ranging campaigns of marches and maneuvers. But if you want to understand the future of warfare in an ever-more-urban world, study the grisly history of sieges.