The sky was crystalline blue the day it happened, and it stayed that way through Thanksgiving. The leaves turned color but remained on the trees. Central Park was dappled in red, russet, and gold. It was the loveliest Indian summer New York had seen in years, as if somehow the city was being compensated for the evil that had overtaken it. Indeed you could sit on a bench in Battery Park in the warm afternoon sunshine and look out on the glistening harbor, and even though the rubble was only a few streets away, everything seemed as before. The promise of New York was still intact, and it would remain the world’s capital. September 11 had not changed that.

Neighborhood Values

But what if calamity should strike again? In November a jetliner broke apart after taking off from Kennedy Airport and plunged into Rockaway Beach in Queens, a neighborhood already mourning the deaths of some 80 residents lost at the World Trade Center. Meanwhile all 251 passengers on the jetliner died. Most were Dominicans by birth and New Yorkers by adoption. The city was stricken, and the Daily News put out a special edition with a single word on the front page: “Why?” The meditation inside began: “In the depths of his despair, the biblical Job pondered a question for the ages, ‘Why do the just suffer and the wicked flourish?’ New Yorkers could be forgiven for wondering if God was testing them yesterday after the city endured its second cataclysm since September 11.” The News is a tabloid, and tabloids sing the songs of the city. If God was testing New Yorkers, then He knew they would somehow survive.

There has always been a grittiness to life in New York. It comes from cramming too many people into too small a space and then insisting they all get along, and although the remarkable thing is that they more or less do get along, there is always some tension. Out-of-town visitors may experience this as rudeness or coldness, but it is really the restless, nervous energy that courses through the city and makes it unlike anywhere else. New York is an idea as much as a place, and whatever its discomforts, people live there by choice. In a way, adversity becomes them.

A month before the attack, a New York Times–CBS News poll asked New Yorkers whether they thought the city would be a better or worse place in which to live in 10 or 15 years—34 percent said it would be better, and 25 percent said it would be worse; 32 percent said it would be the same. But in a similar poll a month after the attack, 54 percent said that in 10 or 15 years the city would be a better place in which to live, whereas only 11 percent said it would be worse; 26 percent said it would be the same. The poll the month before the attack also found that 59 percent of New Yorkers thought life in the city had improved in the previous four years. In the second poll, taken the month after the attack, even as smoke still rose from the World Trade Center, 69 percent said they thought life had improved. No doubt that was an expression of defiance, but there was something else, too. September 11 had been horrendous, but it had also awakened a new appreciation of the city.

When the towers fell they disintegrated into a thick gray cloud that sped outward over the streets and choked the air with dirt. Hundreds of thousands of office workers fleeing the disaster area had to trudge through the cloud on foot. Some were injured, many were in shock, and almost all were preternaturally quiet. There was fear and uncertainty, of course, but no widespread panic, and it was much the same way throughout the city. A hush fell over New York, and people walked the streets. Only the day before they would have avoided eye contact, but now they sought it out. Clumps of people formed and re-formed and asked one another what they had heard. Strangers stopped strangers who looked bereaved and asked if they could help them. Food banks were started and clothing drives begun. Blood-donor volunteers were so numerous on September 11 that hospitals had to turn most away; they did not have the facilities to receive them.

Meanwhile the city at large was in stasis, with bridges and tunnels closed, airports shut down, and buses and subways disrupted; but neighborhoods kept functioning, and the neighborhoods are the bones and sinews of the city. The fabled and celebrated people of New York do not as a rule live in those neighborhoods; but ordinary people do, and life there is not the same as it is in, say, the East 60s or the West Side of Manhattan. To be sure, they are neighborhoods, too, and the city would be poorer without them. They give New York cachet, along with its most advanced thinking. But death and destruction demand a utilitarian response, not advanced thinking. On September 11 the city was reclaimed by the people from the other neighborhoods. They rescued New York physically, and then their values sustained it.

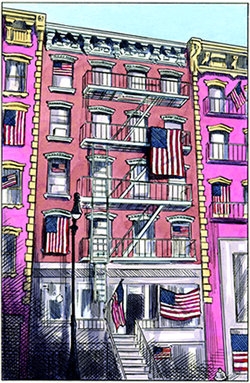

Flags flew everywhere after the attack. They were also hung from apartment and office buildings and fastened to street signs, automobile antennas, and park benches. There were flag decals on city buses. If you looked south from Fifth Avenue and 42d Street, you saw the cloud of smoke over what had been the World Trade Center, but if you looked to the north you saw flag after flag, all the way to Central Park. Granted that flying a flag may be an empty gesture or—remember this was New York—perhaps no more than a fashion statement. Oscar de la Renta put flag decals on his models when he had his winter showing. Other designers did much the same. Nonetheless the patriotic feeling that swept New York was real. When the City Opera opened its season four days after the attack, the entire company came on stage. The company’s artistic director asked the audience to stand for a moment of silence and then join in singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The audience did and people cried. At Broadway shows, audiences sang “God Bless America.” At the Central Synagogue on Lexington Avenue, the congregation sang “My Country ’Tis of Thee” during Rosh Hashanah.

For the city had suffered a terrible wound, and New Yorkers found solace in expressing a love for their country. In a way, they were also rejoining their country. The glory of New York—the idea of New York—is that millions of people of all colors, beliefs, and nationalities can live in one big city while they pursue their dreams and raise their families and not get in one another’s way. So you may think of New York as representing the best of America, although there have long been suspicions that it is really not a part of America at all. It is too decadent and too international, and it dismisses both traditional patriotism and the old-fashioned manly virtues. The heartland is supposed to be a very long distance away.

But that was before the flags flew and people cried when they sang the national anthem, and in fact the heartland had never been as far away as anyone thought. It had always been there in the neighborhoods. After September 11, the city’s Board of Education passed a unanimous resolution requiring all public schools to lead their students each day in the Pledge of Allegiance. In the past, New York’s schoolchildren had always recited the pledge, although in the sixties the practice had waned. At public schools in Manhattan, it seems, the pledge was no longer recited at all. But the old ritual had stayed on at many schools in the outer boroughs. The children there still began their day with the pledge, and often they sang “My Country ’Tis of Thee.”

Heroes of Our Time

The 343 firemen and 23 police officers who gave their lives on September 11 apparently went to schools like that; certainly their children do now. Most had lived in the outer boroughs or the family-friendly towns on Long Island or in New Jersey. A disproportionate 78 of the 343 firemen had lived on Staten Island. With only 440,000 people, it is the least populated of the boroughs; it is also the one furthest removed culturally from the rest of the city. Friendships are built around clubs, schools, and churches—a Catholic high school there lost 23 alumni, about half of them cops or firemen—and alone among the boroughs it consistently votes Republican. Every so often, even if not seriously, Staten Island threatens to secede from New York.

On September 11, however, police and firemen, the firemen especially, of course, became New York’s heroes. They had gone unhesitatingly into a dangerous place and given their own lives while trying to save the lives of others. At a very dear and almost unbearable cost the city learned anew an old lesson. “One fireman stopped to take a breath, and we looked each other in the eye,” a man who had made it to safety from the 86th floor of the North Tower said later. “He was going to a place I was damn well trying to get out of. I looked at him thinking, ‘What are you doing this for?’ He looked at me like he knew very well—‘This is my job.’”

Yes, it was a job, and it was also a way of life that had been preserved despite the pressures to change it. The Fire Department has a distinct culture. Many firemen are Irish American or Italian American, and many had fathers and uncles in the department before them. Officially they are referred to now as firefighters, although the old-fashioned and presumably chauvinistic word firemen is more descriptive. The 343 firemen who died on September 11 were, in fact, all men. In a high-tech age, battling fires and rescuing people is still a low-tech operation. Physical strength and endurance are essential, and the Fire Department has had to resist the ministrations of advanced thinking. Some 25 years ago, when the Police Department set out to recruit more women and members of minorities, it said it would never lower entrance standards. The political culture, however, determined otherwise; the Police Department had to be more inclusive.

But the Fire Department went on as before. Meanwhile firemen from around the country recognized the New York firemen as special; they came from all over on St. Patrick’s Day to march with them in the Fifth Avenue parade and testify to their legendary courage. New York, by contrast, respected the firemen but did not think much about them. New Yorkers could identify the police commissioner, but the fire commissioner was anonymous. Actually that was just as well. There was less pressure on the Fire Department to change its ways, and the bonds that knit the firemen together were allowed to stay intact. New York learned about that on September 11. Among the 343 firemen who died were 21 chiefs, 20 captains, and 47 lieutenants. They had led from the front, and the rank and file had followed. This was tragic and valorous; it was also inspiring. New York had found true heroes.

Moving Forward (with Reverence)

The scene at what was once the World Trade Center has changed with the passage of time. Ground Zero has now become a tourist attraction. At first the city had tried to keep visitors away. Tarpaulins were hung on chain link fences all around the devastated area to discourage people from coming by and staring. The sad and holy place was not to be a spectacle; it demanded a feeling of reverence, and it was not to be commercialized. But by the end of year 2001, the tarpaulins had come down and the fences were moved closer to the crash site. The city even erected wooden platforms on which tourists could stand and get the best views. This may seem inconsistent with the earlier desire to keep people away, but it really was not. The tourists would also spend money and stimulate commerce, and in New York’s way of thinking there was no reason at all that this should be incompatible with feeling reverence.

New York, as always, would be a place where money and dreams could meet, and a terrorist attack would not change that.