The first installment in this series began with the basic analytical framework behind debates about patent reform. Strong patents can facilitate a socially constructive coordination that brings new inventions to market while weak patents lead to a socially destructive coordination among large, established market players in a way that decreases competition. The second installment then explored the ways in which some important provisions of the America Invents Act, now pending in Congress, will inject unending process and undue politics in the systems for testing a patent’s validity.

This installment continues the critique of the America Invents Act by showing how some of the bill’s proposed procedures undermine both property rights and international trade.

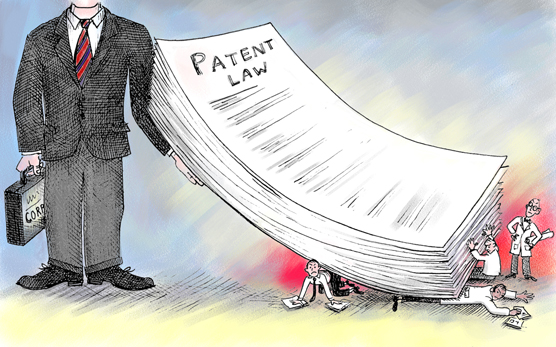

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

The proposed bill includes a new administrative procedure for challenging the validity of patents. The procedure targets only one class of patents it calls "business method patents." This proposed new form of post-grant review subjects these particular patents to ongoing invalidity challenges even after their validity has been thoroughly tested in the existing administrative reexamination proceedings as well as in full civil litigation before a court. Under the provisions of the bill now pending in Congress, these patents can be either tied up in unending process or trashed by an erroneous administrative rejection that then will be especially hard to overturn in court due to the enhanced deference principles of administrative law.

There are many examples of existing property rights in business method patents that have already enjoyed extensive adjudications that covered the myriad aspects of patent validity and infringement after lengthy federal court litigations. For these, the newly proposed administrative process constitutes a taking of fully adjudicated property rights by exposing them to the real risk that these new fangled procedures will wipe them out. One would have to entirely suspend bedrock principles of finality in adjudication to see the administrative erasure of a fully adjudicated property right as a net nullity, legally speaking. And yet, this is the position that some proponents of the pending bill appear to have taken, seeing it as a logical extension of the view that anything the administrative agency giveth, the agency can also taketh away without consequence.

Long established Constitutional doctrine prevents administrative agencies from such takings of property rights without providing their owners just compensation. Congress should seriously consider whether it makes sense to take these property rights at all; but even if it decides to proceed it must recognize that doing so exposes the already huge government deficit to additional billions of dollars in liability. In the case of some of these business method patents, the adjudicated damages that would be wiped out are already in the billions of dollars per patent.

The bill wreaks havoc on property rights, and predictable property rights are essential for economic growth.

What is more, these new procedures can reach any patentee who owns a patent that is sufficiently related to business that it can be called a "business method patent." The scope is enormous and almost any method patent can qualify.

This is bad for any small business that has method patents; and as a result it’s bad for business over all. But it is particularly dangerous in that it seriously undermines the extensive efforts our country has long exerted to ensure predictable enforcement of intellectual property rights overseas.

Especially now, when the economy’s infirmities loom so large, we must focus on the central lesson taught by leading thinkers on both sides of the political aisle: predictable property rights are essential for economic growth, including investment, innovation, and jobs. This is a central message of the work of Nobel Prize winning economists Douglass North and Milton Friedman, who are embraced by Democrats and Republicans, respectively.

Predictable enforcement of intellectual property rights also has been a lynchpin of U.S. trade policy. Such enforcement gave the U.S. the moral authority and bargaining power to bring other countries a great distance in trade negotiations towards enforcing property rights around the world. This was during the extensive negotiations over the treaty known as TRIPS (Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property). One central obligation of TRIPS, which is subject to only a few special exceptions, is to treat all patents the same, regardless of the area of technology. The one provision of that treaty that allows for exceptions requires that they be limited to extreme matters like the protection of the public order.

When word gets out that intellectual property rights are not being taken seriously in the U.S., especially for any class of patents that can be a convenient political target of powerful, well-healed interest groups like banks, our voracious international competitors will pounce. Countries like Argentina, Brazil, China, and India have long been pushing compulsory licenses for drug patents and easy piracy for copyrights in the software and entertainment industries. These countries and others often explicitly seize upon practices in the U.S. that they see as derogating from intellectual property rights. They argue that otherwise narrow exceptions in international treaties allow them to strip away entire areas of intellectual property rights.

If America weakens its patent enforcement at home, it will set a dangerous precedent overseas.

For example, they rely on the narrow exception in TRIPS Article 31, which refers to cases "of a national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency or in cases of public non-commercial use," to support their arguments in favor of the wholesale stripping away of patents rights in particular cases. While those words in TRIPS Article 31 speak only of a very narrow exception, both the Thai and Brazilian governments have argued that even the slightest weakening in America’s domestic patent enforcement, such as the denial of an injunction in particular cases after the Supreme Court’s eBay decision, should be treated as a precedent for their imposition of compulsory licensing for drug patents at rates so low as to be confiscatory.

The major argument that the U.S. has used in response is that we enforce property rights in our country in practically all cases. In the extreme cases when our government does seize property rights, we at least ensure that property owners are paid just compensation.

Making the patents of any industry subject to a new perpetual administrative purgatory at the whim of the large established players will only help our major opponents in international trade do the same for whichever U.S. patent rights they would like to target in their own backyards. This would severely damage the important interests of those components of the U.S. economy that rely heavily on enforcement of intellectual property internationally.

In this installment, we explored some of the features in the America Invents Act that undermine domestic property rights and international trade. Our next installment covers some additional reasons why Congress should kill this bill.