The past several months have witnessed the creation of a multibillion-dollar fiscal stimulus package and heated disagreement over a crucial question: when it comes to stimulating the economy, what works?

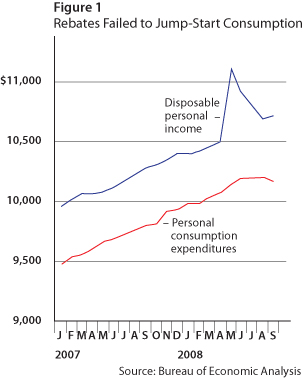

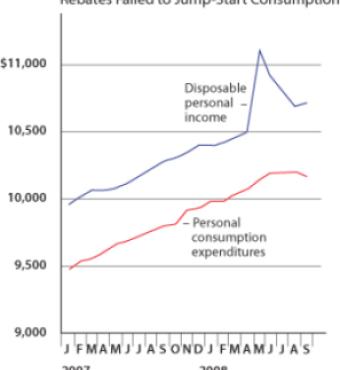

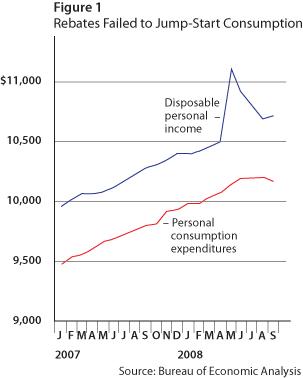

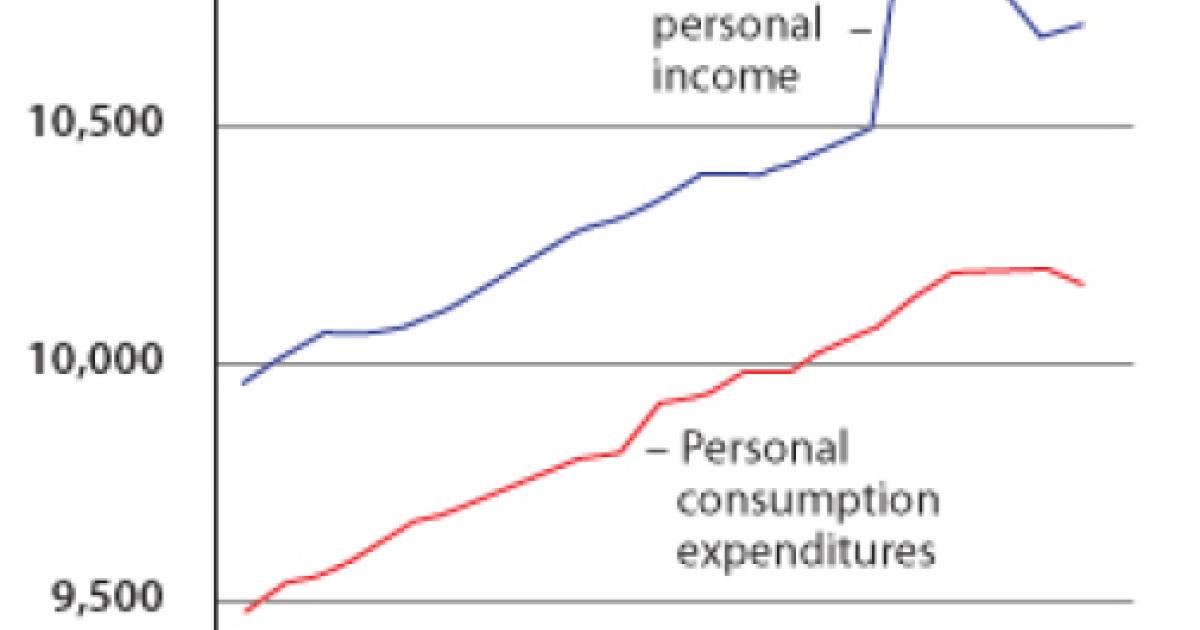

Much can be learned by examining a previous such attempt, the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008. The major part of that first package was the $115 billion temporary rebate program, targeted at individuals and families, that phased out as incomes rose. Most of the rebate checks were mailed or directly deposited last May, June, and July. The argument for these temporary rebate payments was that they would increase consumption, stimulate aggregate demand, and thereby get the economy growing again. What were the results? Figure 1 reveals the answer.

The upper line shows disposable personal income, which is what households have left after paying taxes and receiving transfers from the government, through September. The big blip is due to the rebate payments in May through July.

The lower line shows personal consumption expenditures by households. Notice that consumption shows no noticeable increase at the time of the rebate. Hence, by this simple measure, the rebate did little or nothing to stimulate consumption, overall aggregate demand, or the economy.

These results may seem surprising, but they are not. They correspond very closely to what basic economic theory tells us. According to the permanent- income theory of Milton Friedman, or the life-cycle theory of Franco Modigliani, temporary increases in income will not lead to significant increases in consumption. If increases are longer term, however, as in the case of a permanent tax cut, then consumption is increased by a significant amount.

After years of study and debate, theories based on the permanent-income model led many economists to conclude that discretionary fiscal policy actions, such as temporary rebates, are not a good policy tool. Rather, fiscal policy should focus on the “automatic stabilizers” (the tendency for tax revenues to decline in a recession and transfer payments such as unemployment compensation to increase), which are built into the tax-and-transfer system, and on more-permanent fiscal changes that will positively affect the long-term growth of the economy.

Why did that consensus seem to break down during the public debates about the fiscal stimulus early last year? One reason may have been the apparent success of the rebate payments in 2001. Those rebate payments, however, were the first installment of more permanent, multiyear tax cuts passed that same year and hence were not temporary.

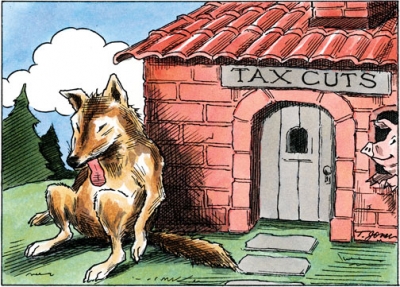

The mantra often heard during debates about the 2008 stimulus was that it should be temporary, targeted, and timely. Clearly, that mantra must be replaced. In testimony before the Senate Budget Committee on November 19, I recommended alternative principles: permanent, pervasive, and predictable.

- Permanent. The most obvious lesson from the 2008 stimulus is that temporary is an unproductive principle if you want to get the economy moving again. Rather than one- or two-year packages, we should look for permanent fiscal changes that turn the economy around in a lasting way.

- Pervasive. One argument in favor of “targeting” the first stimulus package to people who might consume more was that it would create a larger impact. But the targeted stimulus was ineffective. Moreover, such targeting implied that increased tax rates, as currently scheduled, will not be a drag on the economy as long as increased payments to the targeted groups are larger than the higher taxes paid by others. But increasing tax rates on businesses or on investments in the current weak economy would increase unemployment and further weaken the economy. Better to seek an across-the-board approach where both employers and employees benefit.

- Predictable. Although timeliness is an admirable attribute, it is only one property of good fiscal policy. More important is that policy should be clear and understandable—that is, predictable—so individuals and firms know what to expect. Many complain that government interventions in the current crisis have been too erratic. Economic policy—from monetary policy to regulatory policy, international policy, and fiscal policy— works best if it is as predictable as possible.

What could Congress and the Obama administration do to give the economy a real boost? The following fairly bipartisan measures are worth considering:

First, make a commitment, passed into law, to keep all income-tax rates where they are now, effectively making current tax rates permanent. This would be a significant stimulus to the economy because tax-rate increases are now expected on a majority of small business, capital gains, and dividend income.

Second, enact a worker’s tax credit equal to 6.2 percent of wages up to $8,000 as the president proposed during the campaign—but make it permanent rather than a one-time check.

Third, recognize explicitly that the “automatic stabilizers” are likely to be as large as 2.5 percent of GDP this fiscal year, that they will help stabilize the economy, and that they should be viewed as part of the overall fiscal package even if they do not require legislation.

Fourth, construct a government spending plan that meets long-term objectives, puts the economy on a path to budget balance, and is expedited as much as possible without waste and inefficiency.

Some who promoted the 2008 stimulus package have reacted to its failure by saying that we must now switch to large increases in government spending to stimulate demand. But government spending does not address the causes of the weak economy, which has been pulled down by a housing slump, a financial crisis, a bout of high energy prices, and low expectations of future income and employment growth.

The theory that a short-run government spending stimulus will jumpstart the economy is based on old-fashioned, largely static Keynesian theories. Those approaches do not adequately account for the complex dynamics of a modern international economy or for expectations of the future that are now built into decisions in virtually every market.