Iraq is in the midst of an increasingly deadly civil war. Indeed, by one common social science definition (at least 1,000 dead, at least 100 on each side, from internal hostilities in which one side tries violently to change the state or its policies), Iraq’s civil war began in the first year of the “postwar” era and has been particularly bloody ever since. One of the most sophisticated, informed, and objective observers of the conflict, Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, recently estimated that some 50,000 Iraqis have been killed by violence since “major combat operations” ended on April 30, 2003. That is an average of more than 1,000 Iraqis a month—or, in terms proportional to the U.S. population, the equivalent of four September 11 catastrophes every month. And, in recent months, the killing rate has sharply increased. In midJuly, the United Nations estimated that more than 14,000 Iraqis died in the first six months of 2006 and that the death rate rose to more than 3,000 in June alone, but Cordesman regards even those figures as too low.

| The path to civil hell is often marked by a growth in militias—irregular, well-armed, nonstate forces—loyal to contending political parties or identity groups. |

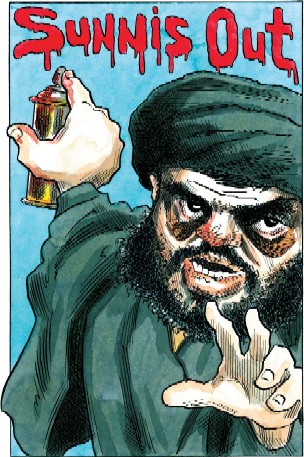

If the civil war began as a largely Sunni insurgency’s killing and terrorizing mainly Shia, Kurds, and Sunni “collaborators,” it has long since taken on a more viciously reciprocal form. Since the spring of 2005, when the United Iraqi Alliance (the coalition of Shia religious parties) took control of the government—and of the Interior Ministry, which controls the police—there has been a marked increase in killings, abductions, torture, and ethnic cleansing of Sunnis. Much of this has been conducted by Shia death squads operating in and alongside police units. Not coincidentally, the Interior Ministry was headed until recently by a leading figure of the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) with ties to its fearsome militia, the Badr Organization.

Iraq’s civil conflict is not about ideology or class or nationalist resistance to the U.S. presence (though the latter does play a role). At root, it is a battle of identities, a struggle not just for power and resources but for dignity and legitimacy. When old hierarchies are disrupted or groups feel threatened or violated, the quest for group security and respect easily mutates into a drive for domination, separation, vengeance, or—at its horrific worst—annihilation. Often, these conflicts are manipulated and mobilized by ethnic elites or rising ethnic challengers as a means to establish and consolidate personal power. Think of Slobodan Milosevic, who used elections to deepen the polarization between not just parties but peoples. Think of Nigeria’s ethnic political parties and their repeated, increasingly bloody contests for political control during the five turbulent years that followed independence in 1960—until the frayed center could no longer hold and the military overturned the wobbly system in early 1966. Think of the consequences: as many as one million dead in the Nigerian civil war.

Like cancer, civil war takes many forms, follows many different courses, and has widely varying etiologies. There is no one set of signals showing that a country is sliding into civil war—or descending from a chronic deadly conflict into allout civil war. But there are characteristic omens. And, in Iraq today, these portend an ugly downward spiral.

A HOLLOW STATE

Civil wars engulf hollow states, those with shallow legitimacy and weak coercive and administrative capacities. Stanford political scientists James Fearon and David Laitin also find that civil wars are significantly more likely in countries that are poor, heavily populated, and politically unstable (because of, say, decolonization or some recent change in government). These structural conditions augur poorly for Iraq, with its depressed national income and marked inability to deliver basic services or economic development. Perhaps even more worrisome has been the inability of the new Iraqi state to build up legitimate security forces that are loyal to it, rather than to the very ethnic and sectarian factions that need to be contained. The militias’ penetration of Iraqi police and commando units (whose uniforms are often worn by those carrying out deadly attacks) is a key factor heightening the prospects of civil war.

| Iraq's conflict is not about ideology or class or nationalist resistance to the U.S. presence. At root, it is a battle of identities, a struggle not just for power and resources but for dignity and legitimacy. |

Indeed, the path to civil hell is often marked by a growth in militias— irregular, well-armed, nonstate forces—loyal to contending political parties or identity groups. The growth in these armed ethnic and sectarian forces has been one of the defining aspects of Iraq’s postwar order. The problem has not only been the dizzying welter of insurgent groups fighting both the U.S. (coalition) Armed Forces and the new Iraqi state, but also the militias of the parties and movements that have positions in that state, such as the Kurdish peshmerga, the Badr Organization, and Muqtada alSadr’s Mahdi Army. For many who worked with the U.S. occupation administration, including myself, one of its most telling and bitter failures was its inability to disarm and demobilize these militias, despite a conceptually elegant plan for this purpose, painstakingly negotiated during the first half of 2004. One of the most alarming aspects of the current situation is the degree to which most informed scenarios to preempt allout civil war depend on a painful step—disbanding the militias—to which their leaders and political sponsors are now more unlikely than ever to agree.

Indeed, the trend is moving in the other direction, as militia recruitment steps up, violence accelerates, and embattled Sunni communities outside the insurgency begin to organize their own militias in response.

POLITICAL POLARIZATION

When there are parties and elections in the mix, civil wars are preceded by deepening polarization. Voters rally around their ethnic solidarities, and parties that try to transcend them are crushed. In Iraq, Kurds have voted almost unanimously for the Kurdistan Coalition (or a small Kurdish Islamic list); most Sunnis boycotted the election in January 2005 and then voted for one or another Sunni list in last December’s elections; and some threequarters of the Shia have voted for the United Iraqi Alliance. From the January transitional election, through the October 2005 constitutional referendum, to the December 2005 parliamentary election, voting in Iraq has increasingly become an identity referendum. Liberal, secular, and nonsectarian alternatives were routed in January, save Iyad Allawi, who scored poorly for an incumbent prime minister (his bloc won only 15 percent of the seats). In December, Allawi and his list absorbed many of the smaller nonsectarian groups and ran as outsiders, critical of the drift and misrule in the Iraqi government. Yet, despite this attempt to transcend identity politics, Allawi’s coalition lost nearly half its seats in parliament. Virtually all the other 250 seats in Iraq’s National Assembly are now held by lists based on religious or ethnic identity.

INFLAMMATORY RHETORIC

Political party and identity group leaders frame the context through which their followers perceive troubling events. If they depict those events as a struggle for group dignity or even survival, their followers will respond in kind, with groupongroup violence. If, instead, they paint acts of outrageous violence as the work of extremists who must be marginalized, then there is at least a chance for the center to hold against the extremes.

For nearly three years now, what passes for stability in Iraq—its ability to avert a slide toward allout war—has owed much to the calming appeal of Ayatollah Ali Al Sistani, who has urged his devoted Shia followers not to be goaded into violent retaliation, despite appalling acts of terrorism and mass murder. For many months now, that patience has been wearing thin, and Sistani’s command over the Shia faithful has been challenged by younger, more radical clerics such as Sadr. A more apocalyptic framing has emerged, in which terrorist acts are seen as “a war against the Shia.”

| Civil war, like cancer, takes many forms, follows many different courses, and has widely varying etiologies. |

The day after the Askariya shrine bombing in February, a Shia newspaper called for war in return “against anyone who tries to conspire against us, who slaughters us every day. It is time to go to the streets and fight those outlaws.” In fact, Sunni and Shia political leaders have been torn between bitterly blaming one another for the crisis, blaming “the troublemaker in the middle” (the Americans)—something it seems all sides can agree on— and calling for restraint and nonviolence. After the initial wave of violent retaliation in February, prominent Sunni and Shia political and religious leaders did reach across the divide to pray together and dampen the fires of violence. But, with each new incident of mass violence and symbolic desecration, the hotheads become more difficult to contain. As Iraqi liberal elder statesman Adnan Pachachi lamented shortly after the February bombing, “I think people are rapidly losing confidence in the political class, and I don’t blame them.”

MAXIMAL AND IRRECONCILABLE DEMANDS

The struggle over rules, policies, and resources has become further polarized as compromise and conciliation give way to maximal and incompatible demands. In Iraq, that process has been accelerated by the constitution approved by Iraqi voters last October. Particularly worrisome are two changes, seen by many Iraqis as destabilizing power grabs, that SCIRI leader Abdul Aziz Al Hakim insisted on during the negotiations in the summer of 2005. One lifts the previous limit (three) on the number of provinces that could coalesce to form a nearly autonomous region. The other gives the “producing regions and provinces” implicit control over revenue from future oil and gas fields. Together, these give rise for Sunni Arabs to the nightmare prospect of an Iraqi “federation,” with a Kurdistan to the north absorbing oilrich Kirkuk; a massive “Shiastan” region to the south, spanning all nine southern provinces and controlling 80 percent of the country’s oil and gas wealth; and a fragmented and impoverished Sunni center left with the desert. If their fears are not allayed, Sunnis could make Iraq bloody and ungovernable for years, if not decades, to come. Without a constitutional compromise over how to share power and resources, distrust and alienation will intensify between groups, along with the violence. This is why U.S. ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad worked so hard to broker a lastminute compromise—announced just four days before the October 2005 referendum—that provided for the new parliament to appoint a constitutional review commission, which would have four months to recommend amendments (to be voted upon by an expedited process). Unfortunately, several months after the new parliament has convened, the dominant parties have shown no interest in constitutional revision, and the Sunnis feel a promise has been broken.

HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES AND ETHNIC CLEANSING

As countries slide toward civil war, the ethnic other is demeaned as less worthy, less moral, and even less human. Once this psychological and moral descent has occurred, gross abuses of human rights follow. By the fall of 2005, accounts were accumulating of several hundred targeted assassinations and disappearances of Sunni Arabs. Often, their horribly abused bodies would be discovered in fields some days later. Numerous reports pointed to the Shia Islamist militias (particularly the Badr Organization and the Mahdi Army), which were believed to have infiltrated the police. Suspicions of official complicity deepened in November with the discovery (by the U.S. military) of a secret underground torture and detention center run by the Interior Ministry.

| Virtually all the seat s in Iraq's National Assembly are now held by lists based on religious or ethnic identity. |

In addition, Iraq’s urban districts and neighborhoods are being “ethnically cleansed.” If the process is not yet quite as ruthless as it was in the former Yugoslavia, the same methods of threat, aggression, and forced eviction are evident, and the trend is becoming increasingly prevalent and bloody. The ethnic expulsions began during the final phase of combat, as the peshmerga poured into Kirkuk and began reversing Saddam Hussein’s campaign of forced “Arabization” that had driven Kurds from their homes and businesses in preceding decades. More recently, mixed Shia and Sunni Arab neighborhoods have steadily become unmixed through intimidation and violence, and even mixed families have had agonizing identity choices thrust upon them. With each new round of warning and killing, the population transfers have accelerated. Meanwhile, Islamic sharia courts established by Sadr’s militants and other radical Islamists have been punishing secular Shia, Sunnis, and Christians. In most parts of Iraq outside Kurdistan, women are being forced to wear the hijah (an extended headscarf ) or to cover themselves completely, and secular Iraqi women live in unprecedented fear. Dozens of Iraqi university professors have been assassinated. More and more Iraqi Christians and middleclass professionals are leaving the country altogether.

MEDIATION: A TALL ORDER

But, if Iraq is in the midst of a civil war, it is not yet in the midst of a total ethnic conflagration. It is vital—not only in simple, humanitarian terms, but for the stability of the region and thus the national security of the United States—that the one not be allowed to morph into the other. If the dam of mass violence bursts, U.S. forces will be (even more than since Saddam fell) too few in number and too weak in legitimacy to stop the flood. The key remains a political settlement that isolates the extremes and avoids a zerosum logic of power. This requires broad power sharing among all the major parties and coalitions, reversing the sectarian militia penetration of the security forces, and revising the constitution to produce a more viable federal bargain.

It is precisely these three goals that Khalilzad has courageously and doggedly pursued since his arrival in the summer of 2005. But he is an overstretched mediator, lacking the diplomatic resources, legitimacy, and time to broker a comprehensive deal on his own. And he is still burdened with a U.S. posture that feeds the Sunnibased insurgency (and thus, increasingly, the Shia counterinsurgency) and the deepening civil war. To get a grip on what is now a bewilderingly fragmented Sunni insurgency, we need a broad dialogue with as many of its elements as possible. Mediating the necessary scope, complexity, and delicacy urgently requires a team effort, including the United Nations and the European Union. In fact, the United Nations has the perfect person to partner with Khalilzad: Lakhdar Brahimi. He is the one person who was able to come from the outside and reason with Sistani, achieving a compromise that saved the transition to sovereignty when it was unraveling. He is the same man who partnered with Khalilzad to bring about a successful transition in Afghanistan.

| With each new incident of mass violence and symbolic desecration, the hotheads become more difficult to contain. |

Even a mediator of Brahimi’s prodigious and proven talents (he also mediated the Taif accord, which helped end the Lebanese civil war), however, would need help and luck, part of which must come through farreaching changes in U.S. policy. Any agreement that pulls significant elements of the Sunnibased insurgency away from violence will require an unambiguous commitment from the Bush administration to eventual withdrawal from Iraq. This means renouncing any intention to seek longterm U.S. military bases in Iraq and a willingness to negotiate some plan for U.S. military withdrawal, even if it stretches over two or three years and is tied to flexible goals rather than to a fixed timetable.

This is not a time for the United States to throw in the towel in Iraq. The consequences of allout civil war—which would now surely follow a precipitous U.S. withdrawal—would be disastrous for everyone except the extremists. It is still possible to find or reconstruct some political common ground. It is still conceivable that the Shia politicians who are now set (in one combination or another) to rule Iraq for the indefinite future can be persuaded to make concessions on the big issues, by the logic that less is more in circumstances when seeking to win everything means civil war. There is still time for farreaching mediation to avert the slide. But the hour grows late.

The content of this article is only available in the print edition.