Critics of school choice programs invoke a two-pronged attack. First, they claim that only the best students with the most motivated parents will take advantage of charter schools and voucher programs—two of the most popular choice vehicles. Presumably, the best students come from families in which parents are involved at home and at school and who provide more support for their child, partnering with the school. Second, critics contend that the flight of the best students leaves behind disproportionately large groups of chronically underperforming, special needs, and problem children who will drag down the rest of the students in the public schools. Teachers will spend inordinate amounts of time on discipline and basics; administrators will be obliged to devote excessive amounts of resources to meet special needs. Critics contend these two effects will doom the traditional public school system to failure.

|

The principal criticisms of opponents of school choice have been badly undermined. |

Indirect evidence to the contrary, however, has been uncovered. These data may be preliminary, but they are compelling.

Enrollment data on charter schools in the 1997–98 school year show that the demographic mix of students enrolling in charter schools is remarkably like that of students in the rest of the school system—the flight of the best and brightest or the affluent or nonminorities is not apparent. The striking similarity of these enrollment patterns rebuts arguments that only the privileged will choose the option of charter schools.

Furthermore, over the past 10 years in the Milwaukee school system, which operates the country’s longest-running publicly provided school voucher program, the performance of students in the system has increased remarkably. In fact, their increases have outstripped those of students in the rest of the state. There may be disputes about the performance of the students who have used vouchers and left the Milwaukee public school system, but the data show that the students left behind are faring quite well. Competition to keep students (and the concomitant funding) may be providing an incentive for the administrators and teachers in Milwaukee to pick up the pace and improve overall performance.

Charter Schools and Demographics

According to a January 2000 report by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), nationwide there are minimal differences in the distribution of minorities, the disadvantaged, and disabled students in charter schools and traditional public schools.

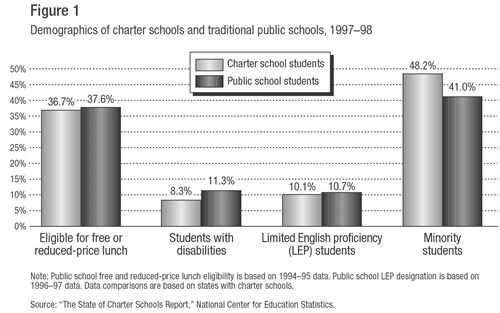

Students’ eligibility for a free or reduced-price lunch under the National School Lunch program (a measure of economic disadvantage) allows for the comparison of poverty levels between students in charter schools and those in public schools in the states that have charter schools. Overall, the total percentage of students eligible for a free or reduced-price lunch is nearly identical: 37 percent in charter schools and 38 percent in traditional public schools (see figure 1).

Furthermore, although charter schools are free of many of the state regulations that govern schools, they are still subject to laws requiring them to provide access to students with disabilities. In fact, some charter schools are specifically designed to serve students with disabilities. For example, in the 1997–98 school year, in Florida 25.1 percent of charter school students had disabilities, compared with 13.4 percent of traditional public school students. According to recent data, students with disabilities made up 8 percent of the population in charter schools overall, compared with 11 percent of public school students. Limited English proficiency (LEP) students are concentrated in a few states in both charter and public schools, but the percentage in both is similar, nearly 10 percent.

|

Early enrollment data on charter schools show that the demographic mix of students enrolling in charter schools is remarkably like that of students in the rest of the school system—the flight of the best and brightest or the affluent or nonminorities has simply not occurred. |

In examining data for the states that have charter schools, slightly more than 50 percent of charter school students are white, compared to almost 60 percent in public schools. NCES concluded that charter schools are more likely to serve black, Hispanic, and Native American students in comparison with traditional public schools.

In short, there do not appear to be large discrepancies between charter school and public school demographics.

Vouchers and Achievement

If critics’ arguments against school choice had merit, one would expect to see a decline in test scores in school districts with voucher programs because the best students are leaving, resulting in lower performing students left behind.

Is choice working in Milwaukee? Let us examine some data from the Milwaukee public schools (MPS) and the Milwaukee Parental School Choice Program. The program, in existence since 1990, when 341 students participated (approximately 0.4 percent of MPS enrollment), has now expanded to include 9,638 students in the 2000–2001 school year (approximately 9.2 percent of MPS enrollment). Interestingly, as participation increased the score of the students left behind increased, not decreased, as alarmists would predict.

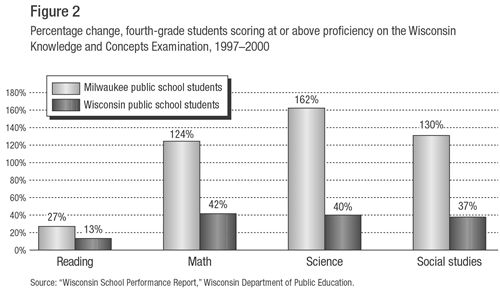

When comparing test scores of MPS students to the rest of the state, MPS students showed remarkable improvement both in absolute terms and relative to the rest of the state. By every test measure at the fourth-, eighth-, and tenth-grade levels in reading, math, science, and social studies, MPS students improved in local, state, and national assessments between 1997 and 2000. For example, the national percentile rank of MPS fourth-grade students improved from a 36 percentile ranking to a 50 percentile ranking in math, 29 to 51 in science, and 35 to 52 in social studies between the 1997–98 and 1999–2000 school years (see figure 2).

Milwaukee public schools should be applauded. Whether the improvement is due to changing pedagogy, improved academic standards, or an increase in resources remains to be determined, but the principal criticisms of voucher opponents have been undermined by these initial results.

If school choice is given a fair chance, its success or failure should be determined by results. If successful, all students—those that stay and those that leave the traditional public school system—would be better off, academically and otherwise. A cautious observation is that all students in Milwaukee public schools are doing better.

Often comparisons and criticisms of charter schools and voucher programs are made with the ideal school system in mind. For most, the ideal system is one with perfect equality: one where resources, academic standards, instructional integrity, and teacher quality are fairly dispersed. The design of our current education system is not perfect. School choice should be given a chance to improve a system that most would agree needs improving.