The big brown trout I was fishing for on the Limay River in Patagonia was nowhere to be found, but I did manage to come across an old hangout of Butch Cassidy. Being from Montana, where the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang pulled off their last job—a holdup of a Union Pacific train—before fleeing to South America, I was happy with this historical catch.

Legend has it that Butch became friends with Jarred Jones, who ventured down to Argentina from Texas in 1887 to make his fortune. Jones didn’t find gold, but he did manage to open a general store at the mouth of the Limay. The old store, which is now a friendly restaurant, still gives off the frontier atmosphere of a century ago.

Jones earned enough money at the store to purchase two big ranches, which he fenced off with barbed wire—the first to be seen around these parts. Today, barbed wire is strung across much of the ninety-eight million hectares of the Patagonian steppe to enclose vast quantities of sheep.

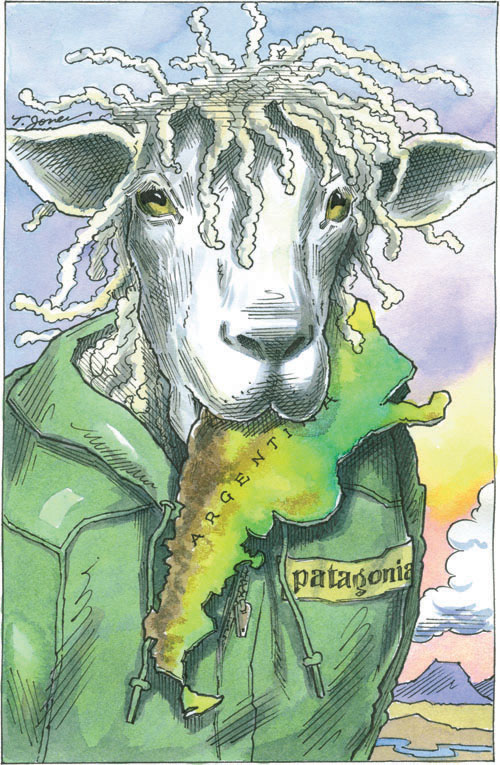

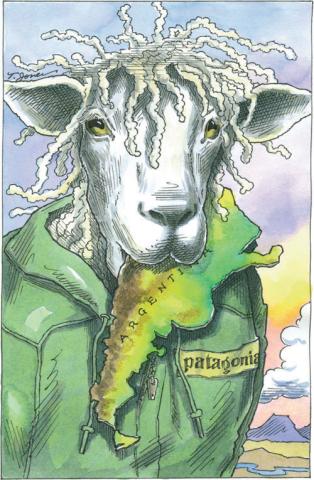

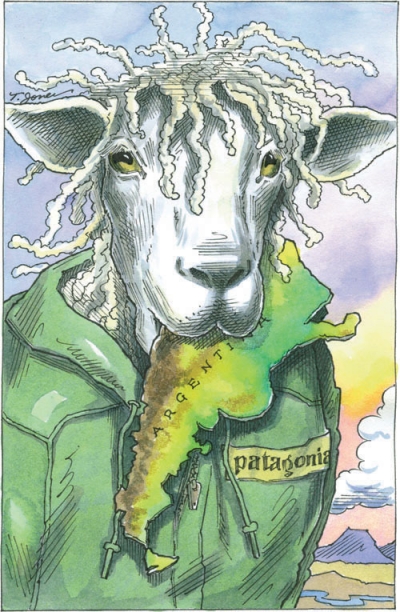

Unfortunately, a flock of sheep can gobble up great expanses of native grasses, and in southern Argentina, they’re clearing some serious vegetation. In addition to vegetation loss, overgrazing equates to lost habitat for other animals, and it damages waterways with runoff and silt from erosion, which affects the fish, which affects tourism.

Paradoxically, sheep—the slayers of grasslands—could become the saviors of the same landscapes and in turn protect fish and other species. Because the plants of the grasslands evolved alongside herbivores, such as guanacos, a little munching is good (and necessary) for the flora. It is also true that companies that have environmental components to their business plans and seek to create goods from natural products, including merino wool, would like to see grasslands flourish for the long term. And tourists like me who want to fish and enjoy ourselves in Patagonia would be willing to pay a price premium for this outcome.

Enter the Nature Conservancy, the outdoor-clothing company Patagonia Inc., and a sheep-industry company called Ovis XXI. Armed with scientific knowledge and market tools, this trilogy is working to conserve more than fifteen million acres of land in Patagonia by 2016. Ovis XXI works directly with the woolgrowers. These consultants know the industry, and they know how to raise sheep without destroying grasslands. The Nature Conservancy brings its science-based knowledge and environmental credibility to help build standards of sustainable grazing. And Patagonia brings the market perspective—buying the wool, networking with others in the supply chain, creating the final products, and using its brand strength to help publicize Patagonian wool.

Most of the land targeted by the Patagonian Grasslands Conservation Project is privately owned, and remains in large, undivided properties of intact native grasslands. Because most landowners face political and economic challenges to their ability to stay in business, they need an incentive to commit to managing resources sustainably. In this case, the carrot is a payment to ranchers for grazing fewer sheep or using more modern and environmentally friendly grazing practices.

Last November, the first shipment of sustainable wool (twenty-nine tons) left Patagonia for Asia to be turned into socks for Patagonia Inc. So far, this arrangement has placed two million acres under sustainable grazing agreements. Time will tell if the environmental protection purchased by conservationists from sheep ranchers will protect grasslands and associated waterways, but the signs are promising.