Historians of revolutions are never sure as to when these great upheavals in human affairs begin. But the historians will not puzzle long over the Arab revolution of 2011. They will know, with precision, when and where the political tsunami that shook the entrenched tyrannies first erupted. A young Tunisian vegetable seller, Mohamed Bouazizi, in the hardscrabble provincial town of Sidi Bouzid, set himself on fire after his cart was confiscated and a headstrong policewoman slapped him across the face in broad daylight. The Arab dictators had taken their people out of politics, they had erected and fortified a large Arab prison, reduced men and women to mere spectators of their own destiny, and the simple man in that forlorn Tunisian town called his fellow Arabs back into the political world.

From one end of the Arab world to the other, all the more so in the tyrannies ruled by strongmen and despots (Libya, Syria, Egypt, Yemen, Algeria, and Tunisia), the Arab world was teeming with Mohamed Bouazizis. Little less than a month later, the order of the despots was twisting in the wind. Bouazizi did not live long enough to savor the revolution of dignity that his deed gave birth to. We don’t know if he took notice of the tyrannical ruler of his homeland coming to his bedside in a false attempt at humility and concern. What we have is the image, a heavily bandaged man and a tacky visitor with jet-black hair, a feature of all the aged Arab rulers—virility and timeless youth are essential to the cult of power in these places. Bids, we are told, were to come from rich Arab lands, the oil states, to purchase Bouazizi’s cart. There were revolutionaries in the streets, and there were vicarious participants in this upheaval.

A silent Arab world was clamoring to be heard, eager to stake a claim to a place in the modern order of nations. A question had tugged at and tormented the Arabs: were they marked by a special propensity for tyranny, a fatal brand that rendered them unable to find a world beyond the prison walls of the despotism? Better sixty years of tyranny than one day of anarchy, ran a maxim of the culture. That maxim has long been a prop of the dictators.

There is no shortage of autopsies of the Arab condition, and I hazard to state that in any coffeehouse in the cities of the Arabs, on their rooftops that provide shelter and relief from the summer heat, the simplest of men and women could describe their afflictions: the predator states, the fabulous wealth side by side with mass poverty, the vanity of the rulers and their wives and their children, the torture in countless prisons, and the destiny of younger men and women trapped in a world over which they have little if any say.

No Arabs needed the numbers and the precision supplied by “development reports” that told of their sorrows, but the numbers and the data were on offer. The Arab Human Development Report of 2009—a United Nations project staffed by Arab researchers, the fifth in a series—provided a telling portrait of the world of 360 million Arabs. They were overwhelmingly young, the median age twenty-two, compared with a global average of twenty-eight. They had become overwhelmingly urbanized: 38 percent of the population lived in urban areas in 1970; it was now close to 60 percent. There had been little if any economic growth and improvement in their economies since 1980. No fewer than 65 million Arabs were living below the poverty line of $2 a day. New claimants were everywhere; 51 million new jobs have to be created by 2020 to accommodate the young. Tyranny kept these frustrations in check. Eight Arab states, the report stated, practiced torture and extrajudicial detention. And still, the silence held. Bouazizi and his deed of despair brought a people to a reckoning with its maladies.

A CHILLING EXAMPLE OF DESPOTIC POWER

Why have the Arabs not raged before as they do now—why has there not been this avalanche of anger that we witnessed in Tunisia and Egypt and Libya and Syria? Why did the Arabs not rage last year, or the year before that, or in the last decades? An answer, one that makes the blood go cold, is Hama.

In retrospect, the Arab road to perdition—to this large prison that the crowds have set out to dismantle—must have begun in that Syrian city in 1982. A conservative place in the central Syrian plains rose in rebellion against the military regime of Hafez Assad. It was a sectarian revolt, a fortress of Sunni Islam at odds with Assad’s Alawite regime. The battle that broke out in February of that year was less a standoff between a government and its rivals than a merciless war between combatants fighting to the death. Much of the inner city was demolished, and perhaps twenty thousand people perished in that cruel fight. The ruler was unapologetic; he may have bragged about the death toll. He had broken the old culture of his country and the primacy of its cities.

Hama became a code word for the terror that awaited those who dared challenge the men in power. It sent forth a message in Syria, and to other Arab lands, that the tumultuous ways of street politics and demonstrations and intermittent military seizures of power had drawn to a close. Assad would die in his bed nearly two decades later, bequeathing power to his son, Bashar, who wields it today. Tyranny and state terror had yielded huge dynastic dividends.

The heart went out of Arab dissent and ideological argumentation. A new despotic culture took hold; men and women scurried for cover, lucky to escape the rulers’ wrath and the cruelty of the secret police, and the informers. Terrible men, insulated from their subjects (the word is the right one), put together regimes of enormous sophistication when it came to keeping their tyrannies intact. State television, the newspapers, mass politics, and the countryside spilling into the cities aided the despotisms. The tyrants, invariably, rose from modest social backgrounds. They had no regard for the old arrangements and hierarchies and for the limits a traditional society placed on the exercise of power.

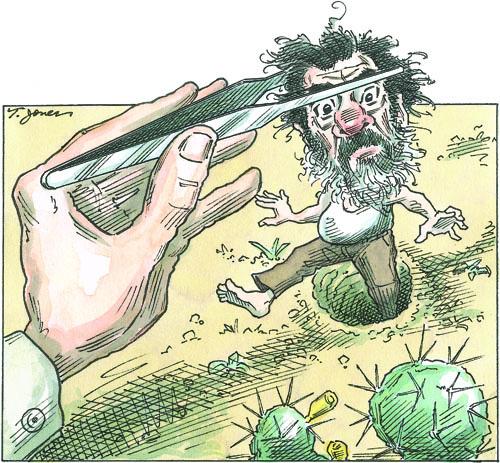

Men like Muammar Gadhafi of Libya and Saddam Hussein of Iraq, like Hafez Assad of Syria, were children of adversity, and they were crueler for it, because traditional Arab society exalted pedigree and high birth. As the Arabs would put it—in whispers, in insinuations—no one knew the names of the fathers of these men who fell into things and acquired political kingdoms of their own. The details varied from one Arab realm to another, but at heart the story was the same: a tyrant had emerged and restructured the political universe to his will. Milder authoritarianisms gave way to this “sultanist” system.

When the Egyptian rebellion erupted, it was foreordained that it would focus on the ruler and his family. Egyptians had grown weary of Hosni Mubarak, and the prospect of another Mubarak waiting in the wings was an affront to their dignity. The tyranny had sullied them, and they wanted to be done with the despot: “Irhall” (“Be gone”), the crowd would chant in unison. No script was on offer—no revolution has ever followed a script—but the people of Egypt were willing to trade this tyranny for the uncertainty of what was to come. Now the world-weary could tell them that their revolt may yet be betrayed, that they will break their chains only to forge new ones, that the theocrats are destined to replace the autocrats. But grant the Egyptian people their right to swat away these warnings.

Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia was shaped of the same mold as Mubarak. He had been a man of the police and the security services. True, his predecessor, the legendary Habib Bourguiba, hero of Tunisia’s independence, had ruled uncontested for three decades until Ben Ali pushed him aside in 1987. But Bourguiba was a cultured man; he knew books and literature; he had high aspirations for his country and its modernity. His political history placed him above his contemporaries, and he could take his primacy for granted. It would have appalled him to think of himself as a warden of his people—a thought and a reality that never troubled Ben Ali.

The greed of Ben Ali’s family and his in-laws, the speed with which they all clamored out of the country at the first sign of danger, told volumes about this despotism. There was no patriotism and love of home here: a predator and his ambitious wife, the hairdresser who had come out of nowhere to the pinnacle of power, made a run for it. It had been quite a racket for them, and it was now time to quit the land they had plundered and enraged.

This, too, the plundering, marks a great discontinuity with the past. The despots of the day dispose of enormous wealth. The fortunes of the rulers, an Arab businessman once said to me, are the real weapons of mass destruction in the region.

REJECTING THE RULING CASTE

One way or the other, the men at the helm became a ruling caste. They harked back to a pattern of rule that had befallen the world of Islam after the demise of the Baghdad caliphate in the thirteenth century to the rule of the Mamluks, soldiers of fortune who carved out kingdoms of their own and kept apart from the populations they ruled. Gone was the continuity between the ruler and the ruled that had been the hallmark and the promise of the advent of nationalism. The autocrats were now feared and reviled. A distinguished liberal Egyptian formed in the liberal interwar years, the late scholar and diplomat Tahseen Basheer, said of these men that they became “country owners.”

The rulers grew older and obscenely wealthy, their populations younger and more impoverished. These autocrats in the national-security states put to shame the old monarchies in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the Emirates. In the monarchies and principalities there has always existed a “fit” between monarchs and princes, and their people. There has never been a cult of personality in these monarchies: the Stalinist cult that afflicted Saddam’s Iraq, Hafez Assad’s Syria, and Gadhafi’s Libya is abhorrent to them. The Bedouin ethos that still legitimizes the monarchies has no room for such deference to the ruler.

Monuments to kings are heresy to the Saudi rulers. The affection and concern displayed by ordinary Saudis for the ailing King Abdullah stands in sharp relief against the animus toward Mubarak and Ben Ali and Assad and Gadhafi. The Sabahs of Kuwait, the ruling family in that city-state since the mid-eighteenth century, inspire no fear in Kuwaitis; no “visitors at dawn” haul off Kuwaitis to prison, as is the norm in the republics of terror. Before the age of oil, the Kuwaitis had been seafarers and pearl divers, and the Sabahs were the ones who stayed behind to look over the affairs of the place. They had respect and privilege, but there was no space for grand ambitions and pretensions. The merchants held their own and still do: the wealth of the merchant families is more than a match for the revenues of the Sabahs. Nor do the other principalities differ in this regard. State terror is alien to them.

Tiny Bahrain is something of an exception, afflicted as it is by a sectarian split between a Sunni ruling dynasty and a restive majority Shia population. But on the whole, the monarchies have always ruled with a lighter touch. Who in today’s republics of the whip and of state terror would not call back the monarchs of old? Nasab, or genealogy—inherited merit—is revered in the practice and life of the Arabs. It reassures people at the receiving end of power and hems in the mighty, connecting them to the deeds and reputations of their forefathers.

So three despots have fallen: Saddam Hussein in 2003; Ben Ali; and Mubarak. Saddam’s regime was of course decapitated by American arms. Ben Ali and Mubarak were brought to account by their own populations. This revolt is an Arab affair through and through. It caught the Pax Americana by surprise; no one in Tunis and Cairo and beyond was waiting on a green light from Washington. The Arab liberals were quick to read Barack Obama, and they gave up on him. They saw his comfort with the autocracies, his eagerness to “engage” and conciliate the dictators.

From afar, the “realists” tell the Arabs that they are playing with fire, that beyond the prison walls there is danger and chaos. Luckily for them, the Arabs pay no heed to these realists, and can recognize the “soft bigotry of low expectations” that animates them. Arabs have quit railing against powers beyond and infidels and foreign conspiracies. For now they are out making and claiming their own history.