As the U.S. military engagement entered its sixth year in mid-March, Iraq finally seemed in many ways to be turning a corner toward stabilization. Even jaundiced journalists were conceding that the military surge, which had taken effect by the summer of 2007, was significantly helping security. Whole neighborhoods had returned to a more normal commercial and social life. Terrorist acts were way down, with multiple-fatality bombings dropping by more than two-thirds from their peak in the bloody year of 2006. With the change in American force levels and military strategy, the average daily death toll of Iraqis dropped from more than 100 a day to 20.

The improvement was palpable. Iraqi police and military deaths fell from a peak of 300 in April 2007 to 110 in February 2008. Deaths of U.S. soldiers also dropped sharply, from more than 100 per month in late 2006 and early 2007 to under 40 per month in late 2007 and early 2008. But these casualties still were painful losses. American troops continued to suffer wounds, both physical and psychological; 600 –700 Iraqis were dying every month; and the violence in Iraq had declined only to the still-serious level of insecurity that prevailed in 2005.

Other important indications of stabilization were gathering momentum in Iraq. Accompanying the surge in U.S. forces was a large and presumably more lasting increase in Iraqi forces: 100,000 more soldiers and police officers in place, along with about 80,000 “concerned local citizens”—members of community militias armed and funded by the United States to turn against Al-Qaeda and other violent forces. Beyond the increased levels of forces was a dramatic change in American strategy under General David Petraeus, focused on the Sunni Arab communities in Anbar province that had become a safe haven for Al-Qaeda in Iraq. After years of denial and failure, the U.S. military had finally forged tactical alliances with many of the Sunni Arab resistance forces against the greater common enemy, Al-Qaeda. And the U.S. Army had turned to classic counterinsurgency tactics of taking and holding towns and neighborhoods and working earnestly to win “hearts and minds.” Accompanying this were more-effective civilian efforts to build local and provincial governing capacity from the bottom up.

All this came at a propitious moment. Sunni Arab communities were fed up with the thuggish domination of Al-Qaeda in Iraq; provided with weapons, money, and assurances, they turned against Al-Qaeda and expelled it from most of the Sunni communities where it had taken root. While still incomplete, this has been the single biggest achievement of the surge, with huge implications for Iraqi and U.S. security. In the Shiite communities, the militant cleric Muqtada al-Sadr pulled back from military conflict and authorized a cease-fire by his Mahdi Army, although an eruption of fighting in Basra in March 2008 raised doubts about the Iraqi military ’s ability to maintain security.

If security developments offered cause for hope in Iraq, political developments were another story. By the time Petraeus and Ambassador Ryan Crocker testified to Congress on April 8, it was apparent that the United States was no closer to success in Iraq (the kind that would enable American forces to depart and the country to stand on its own); it had only drawn back from the brink of failure. As the ranking Republican senator on the Foreign Relations Committee, Richard Lugar, observed in the Senate hearings that day, “Simply appealing for more time to make progress is insufficient.” Increasingly, Bush administration supporters of the Iraq mission were demanding benchmarks on political accommodation and stabilization and pressure on the disparate Iraqi parties to meet those benchmarks.

Iraq’s divided parties had been creeping toward some limited agreements on divisive matters such as reintegration of some of the purged former Baathist officials. But as a comprehensive analysis by the U.S. Institute of Peace (released on the eve of the April 8 hearings) made clear, the political situation in Iraq remains adrift, hobbled by “a weak and divided central government with limited governing capacity.” As the analysis points out,

Mistrust among leaders in Baghdad remains high. Key ministerial posts have remained unfilled for months. Important legislation —on de-Baathification, amnesty, provincial powers, and the budget—has passed, but implementation is uneven. The Iraqi security forces have been strengthened but remain far from able to sustain themselves or fight insurgents and militias on their own. Mixed loyalties within the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) continue to pose a threat.

At the same time, corruption is rampant, draining the government’s energy and capacity to rebuild the country, and little progress has been made toward resolving the big constitutional questions that continue to polarize the country.

As Petraeus conceded, the security progress has been fragile and reversible, in large part because it has not been matched by political progress. In fact, by the time Petraeus testified, violence levels had already risen from their low points during the surge. From the beginning, Petraeus and U.S. military commanders have stressed that the military is only one element of Iraq ’s stabilization, and that without effective political accommodation among Iraqis, no security gains can last.

Iraq’s fundamental problem remains the lack of a broad political agreement on the constitutional shape of the country. We are now nearly two years past the date when the Iraqi constitution was to have been amended to resolve such key issues as control and distribution of the oil revenue, the federal structure of the country, and the structure of executive power at the center. Iraq cannot progress toward stability until all the major parties agree on the core constitutional question: how will wealth and power be shared?

Iraq’s factions are in a political holding pattern. The established Shiite parties—the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI) and Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki’s Dawa—do not want to give up their control of the central government and the provincial governments in the south. In particular, ISCI (historically close to the Islamic Republic of Iran) is determined to draw all nine Shiite provinces into one superregion, containing most of Iraq ’s oil and half its population. This would become an Islamist state within a state, dominating the country ’s politics and resource flows and linking up closely with Iran. That prospect is flatly unacceptable to the Sunni Arabs but agreeable to the two ruling Kurdish parties, which are willing to trade off national-level concerns in exchange for preserving the powers of the Kurdistan region and seeing it absorb the oil-rich city of Kirkuk (though a referendum was to have been held by now). At the heart of the constitution adopted in 2005 was this power bargain between the major Shiite and Kurdish parties: oil for oil, a superregion for the Shiites, and Kirkuk for the Kurds.

The constitutional stalemate is far from the only political challenge confronting Iraq this year. Social frustration is rising over the feckless, incompetent, and massively corrupt government. Long-delayed provincial elections are due by October, and there remains a huge question of whether they will be reasonably free, transparent, and fair. If those conditions are met, the ruling parties figure to suffer significant losses in many of the eighteen provinces as punishment for their corrupt and oppressive conduct in office. Additionally, in the south, there is a growing nationalist reaction among the Shiites against the activities there of Iranian agents who were invited in by ISCI. The increased violence within the Shiite communities in early spring 2008, and the crackdown on Sadr ’s Mahdi Army, had much to do with the maneuvering before these elections, including ISCI ’s effort to pre-empt a vigorous ballot box challenge by Sadrist forces.

For the United States, difficult times lie ahead, and neither the Republicans nor the Democrats seem likely to put forward a viable solution. President Bush and his prospective Republican successor, Senator John McCain, seem prepared to keep U.S. forces in Iraq indefinitely, demanding nothing specific of Iraq ’s self-absorbed parties except that they keep showing an effort. Yet Senators Hillary Rodham Clinton and Barack Obama also offer no incentive for the Iraqi parties to negotiate, promising only to implement a rapid and more or less fixed timetable for the withdrawal of U.S forces.

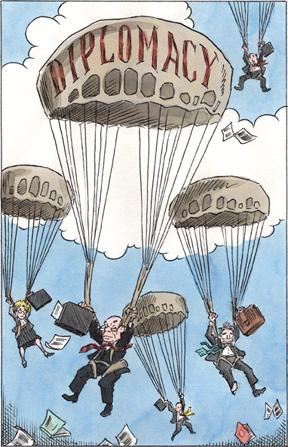

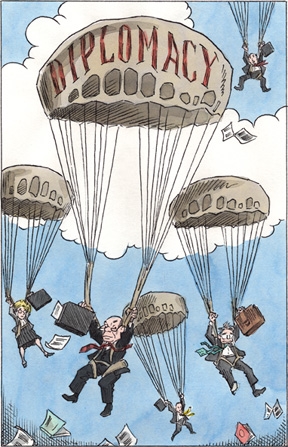

We need a more flexible and tough-minded approach. The only way Iraq’s parties will make the necessary political compromises is with a “diplomatic surge” of intense pressure and incentives. They must understand that the United States will not stay indefinitely, and that failure to negotiate and compromise in good faith would lead to an expedited U.S. withdrawal and unspecified punishment of particularly recalcitrant parties. They must also understand that political progress toward accommodation in Iraq could stretch out the timetable for the American drawdown, buying time they need to build stability.

Negotiating a new constitutional bargain requires the active partnership of the United Nations and probably the European Union, both of which have the standing and leverage to include Iraq ’s aggrieved actors and its regional partners, including Iran, and to broker the big constitutional issues.

The shape of a viable bargain has been clear for many years. ISCI would need to give up its ambition of a single, nine-province superregion but could be granted a federal system with the eventual ability to lobby for creation of smaller regions (of up to three provinces each, as the interim Iraqi constitution had permitted). The Kurds would keep their own region as part of a federal system and sooner or later would probably be allowed to absorb Kirkuk as well; developing new oil fields, however, would remain a prerogative mainly of the central government, not, as the Kurds and ISCI wish, regional governments. The Sunnis would have to reconcile themselves to being a minority political force, but their provinces would be constitutionally guaranteed a fair and automatic distribution of the oil revenue, more or less in proportion to each province ’s share of the population.

The Bush administration’s military surge, with its many tactical alliances and adjustments, has created a new chance to stabilize Iraq at the level where it most counts: politically. That is all the surge could ever do. But it remains to be seen whether the administration (and then the Iraqis themselves) will seize the opportunity. If not, the next American president is likely to take office as Iraq slips back into a much deeper crisis, leaving the United States with a much more dreadful set of choices.