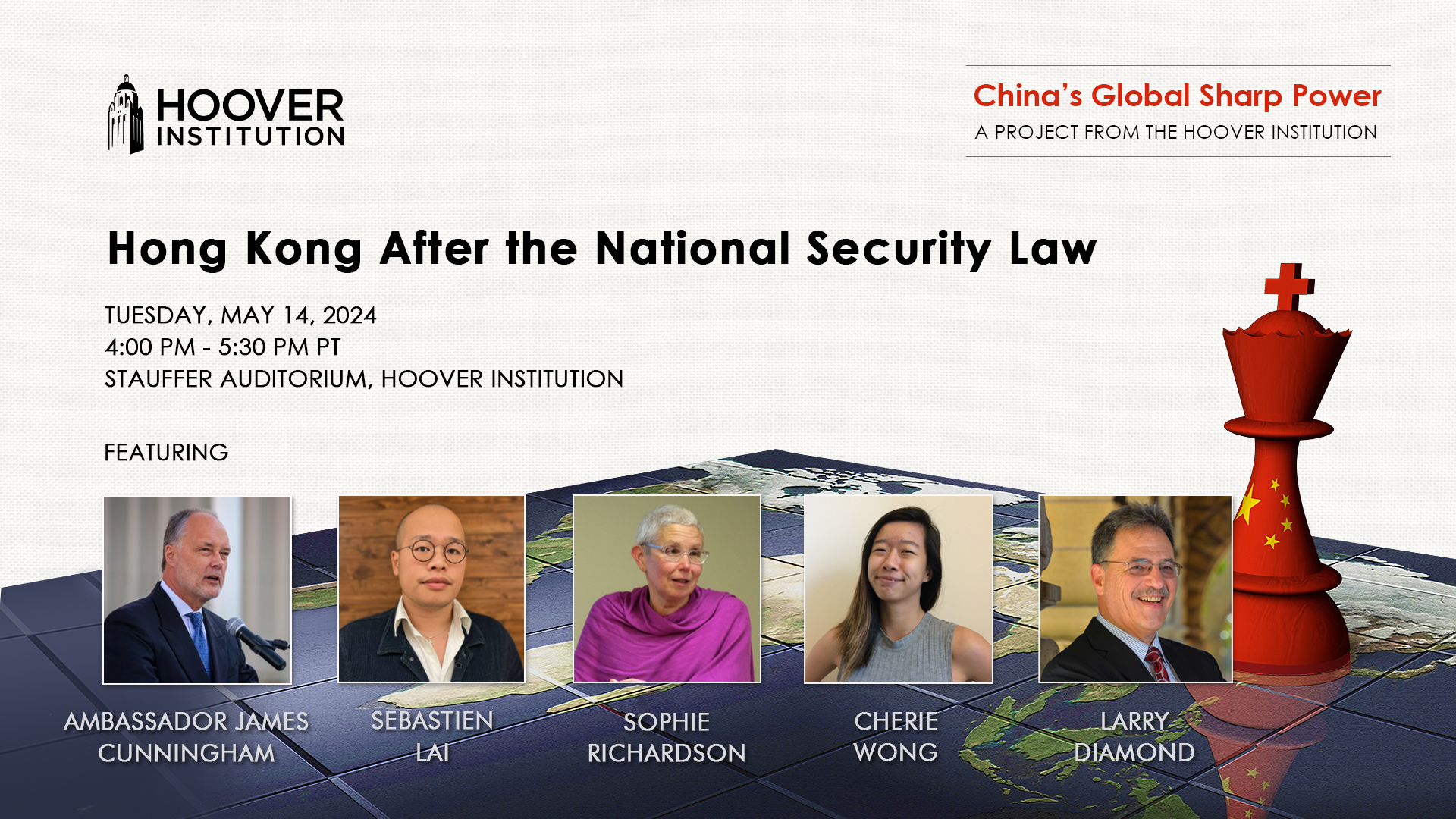

The Hoover Project on China’s Global Sharp Power held Hong Kong After the National Security Law on Tuesday, May 14 from 4-5:30pm PT.

This event presented perspectives on the current political and civic climate in Hong Kong since the passage of the National Security Law on June 30, 2020 and the imposition of Article 23 on March 23, 2024. How have these developments fit into the broader history of the struggle for democracy in Hong Kong? What has changed in Hong Kong’s once vibrant civil society? What is the latest on the trials of pro-democracy activists? How have diasporic advocates constructed a Hong Kong political identity in exile?

Four panelists—Ambassador James Cunningham, the Chairman of the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong and former Consul General of the United States to Hong Kong and Macau (2005-2008); Sebastien Lai, a democracy advocate and son of jailed Hong Kong businessman and publisher Jimmy Lai; Sophie Richardson, the former China Director at Human Rights Watch; and Cherie Wong, the former leader of Alliance Canada Hong Kong (ACHK)—will discuss these issues and more in a conversation moderated by Hoover William L. Clayton Senior Fellow Larry Diamond.

ABOUT THE SPEAKERS

Ambassador James B. Cunningham retired from government service at the end of 2014. He is currently a consultant, a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, an adjunct faculty member at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School, and Board Chair of the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation. He served as Ambassador to Afghanistan, Ambassador to Israel, Consul General in Hong Kong, and Ambassador and Deputy Permanent Representative to the United Nations. Ambassador Cunningham was born in Allentown, Pennsylvania and graduated magna cum laude from Syracuse University. He is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, the Asia Society, the National Committee on US-China Relations, and the American Academy of Diplomacy.

Sebastien Lai leads the international campaign to free his father Jimmy Lai, the pro democracy activist and publisher currently jailed by the Hong Kong government. Having had international calls for his release from multiple states including the US and the UK, Jimmy Lai’s ongoing persecution mirrors the rapid decline of human rights, press freedom and rule of law in the Chinese territory.

Sophie Richardson is a longtime activist and scholar of Chinese politics, human rights, and foreign policy. From 2006 to 2023, she served as the China Director at Human Rights Watch, where she oversaw the organization’s research and advocacy. She has published extensively on human rights, and testified to the Canadian Parliament, European Parliament, and the United States Senate and House of Representatives. Dr. Richardson is the author of China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence (Columbia University Press, Dec. 2009), an in-depth examination of China's foreign policy since 1954's Geneva Conference, including rare interviews with Chinese policy makers. She speaks Mandarin, and received her doctorate from the University of Virginia and her BA from Oberlin College. Her current research focuses on the global implications of democracies’ weak responses to increasingly repressive Chinese governments, and she is advising several China-focused human rights organizations.

Cherie Wong (she/her) is a non-partisan policy analyst and advocate. Her influential leadership at Alliance Canada Hong Kong (ACHK), a grassroots community organization, had garnered international attention for its comprehensive research publications and unwavering advocacy in Canada-China relations. ACHK disbanded in November 2023. Recognized for her nuanced and progressive approach, Cherie is a sought-after authority among decision-makers, academics, journalists, researchers, and policymakers. Cherie frequently appeared in parliamentary committees and Canadian media as an expert commentator, speaking on diverse public policy issues such as international human rights, foreign interference, and transnational repression.

Larry Diamond is the William L. Clayton Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, the Mosbacher Senior Fellow in Global Democracy at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI), and a Bass University Fellow in Undergraduate Education at Stanford University. He is also professor, by courtesy, of political science and sociology at Stanford. He co-chairs the Hoover Institution’s programs on China’s Global Sharp Power and on Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region.

_____________________

Transcript

Larry Diamond: [00:00:00] Greetings everyone. we're going to do something that doesn't always happen at Stanford University. We're going to start on time. And part of the reason why we're going to start on time is because we have a webinar audience. That is with us and is waiting and, expects us to start on time and they can't schmooze with one another the way we can in person.

I'm Larry Diamond. I'm a senior fellow here at the Hoover Institution. and, with Glenn Tifford, I lead the program on China's global sharp power here, at, at Hoover. I also want to thank Francis Hiskin for her work and organizing this. Thank you, Francis. [00:01:00] and thank you to the, remarkable staff here at Hoover.

Janet, thank you for you and your team, who do so much to make everything work so smoothly. the way we're going to proceed, is that I am in a moment going to introduce our four speakers, and then I'm going to, dim the lights, by appeal to our staff, and we're going to show a remarkable, short video, a very powerful video, with the person, featuring the person who is not in this room, Who we dearly wish was in this room, but who is sitting in a jail in Hong Kong and whose spirit is in this room and whose son is in this room, and that is Jimmy Lai.

And then we will have, each of [00:02:00] our, panelists speak for about seven minutes, and then I'll have a conversation with them. And then you can have a conversation with them by writing a question on the note cards, that we've Passed out or on the pads of paper that are on your chair, and we'll come and collect those and organize them and read them.

So let me begin with the son of Jimmy Lai, that is Sebastian Lai, immediately to my left. he leads the international campaign to free his father, Jimmy Lai, the pro democracy, activist and publisher. Currently jailed, and I will say as a political prisoner by the Hong Kong government, having had international calls for his release from multiple states, including the U.

S. In the U. K. Jimmy lies. Ongoing persecution mirrors the rapid decline of human rights in Hong Kong as well as press [00:03:00] freedom and the rule of law. Our next speaker, Knows the Hong Kong situation well as an American who served there. as a cons general from 2005 to 2008. I was very privileged to be able to visit when he was there.

And thank you for receiving me. he is Ambassador James B. Cunningham, prior to, serving as, US Cons General, in Hong Kong. He served as ambassador and deputy permanent representative to the United Nations. And after his service in Hong Kong, he was U S ambassador to Afghanistan and then to Israel.

So the United States government has tapped him multiple times for very difficult assignments. and he's had a very, distinguished career as an American diplomat, as a career [00:04:00] minister. And he's currently a consultant. A non-resident, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, and an adjunct FA adjunct faculty member at his alma mater Syracuse University at its Maxwell School of Public Policy.

He's also the board chair of the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation. Next we have Sophie Richardson, a longtime activist and scholar of Chinese politics, human rights, and foreign policy. Currently a visiting scholar across the way here at the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law at Stanford.

I think you know her best. As the China director at Human Rights Watch from 2006 to 2023. There she oversaw the organization's research and advocacy. She's published extensively on human rights in China. She's the author of China, Cambodia, and the five principles of [00:05:00] peaceful coexistence. She has her doctorate from the University of Virginia.

And her current research focuses on the global implications of democracies around the world, responding so weakly to increasingly repressive Chinese governments. Finally, Sherry Wong is a nonpartisan policy analyst and advocate, and, her influential leadership Alliance Canada, Hong Kong, a grassroots community organization has garnered international attention for its comprehensive research publications and eloquent unwavering advocacy in Canada, China relations.

Recognized for her nuanced and progressive approach, Sherry Wong is a sought after authority among decision makers, academics, journalists, researchers, and policy [00:06:00] makers. She has frequently appeared before parliamentary committees and Canadian media. As an expert commentator speaking on diverse public policy issues such as international human rights and transnational repression.

So if you've just come in, you've come in at exactly the right time because the video clip we're going to show you now is so deeply moving. That I am going to get out of my seat to watch it for a third time. I

Lai: have

Larry Diamond: long

Lai: determined not to be frightened by fear.

Peter: Jimmy Lai, a native of mainland China, Jimmy, reached Hong Kong in a fishing boat as a stowaway at the age of 12.

Then came the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre. Mr. Lai sold his stake in Giordano, founding the pro democracy Next magazine, and the Apple Daily, again a pro democracy outlet, We have to confront the biggest enemy. [00:07:00] In the democracy protests that swept Hong Kong, Mr. Lai, now in his 70s, insisted on marching in front, where the authorities could see him.

Lai: China is determined to take away our freedom.

Peter: Mr. Lai vigorously opposed the new national security law that Beijing was then threatening to impose on Hong Kong.

Lai: I think one day China has to unravel.

Peter: Beijing did impose the new law, imposed it.

Lai: I think that maybe the legal system now is being under the influence of Beijing.

Peter: And

Lai: that

Peter: some 200 police raided Mr. Lai's offices, handcuffed him, and then before taking him away, walked him around the floor of his newsroom so that all his journalists would see what was happening.

Lai: I just do what I have to do, say what I have to say without thinking about the consequences.

Peter: And you argue, what, that Western values are in fact universal?

You can be a good Chinese and protest in favor of [00:08:00] democracy and freedom

Lai: of speech? We have to fight. Otherwise, we will lose everything. If we lose freedom, we will lose everything. I think that is the dim hope we still have. If the consequences comes, I will just accept it as my destiny. And if it's my destiny, it's God's blessing.

This is the way I look at it. I can't change it. if now giving myself, I come to think as a redemption of myself.

Peter: Not only are you facing prison, you're out almost a hundred million dollars of your own money to continue what you've been doing.

Lai: Is that fair? It's very simple because we have to fight.

We have been fighting for freedom for 30 years. Democracy is only the means to the end. The end is freedom. Any suffering is a blessing. Any suffering is experience. I don't treat suffering as something very tough. I'm almost 73. [00:09:00] maybe I need another way to understand life, another way to live my life to a fuller extent.

Maybe suffering can help this. By giving myself I feel the happiness of redemption. I think this is the way I accept my fate. I will have to fight to the last day.

Larry Diamond: What we're going to do in this session now is ponder what has happened to Hong Kong since the passage of the national security law on June 30th of 2020.

And the imposition of Article 23 on March 23rd, 2024. this was not the beginning of the repression of Asper and denial of aspirations for democracy in Hong Kong. and so we want to look back, further in time and ponder, what has [00:10:00] happened to Hong Kong. It's rule of law. It's democratic aspirations.

It's remarkably vibrant civil society. It's incredible free press, which apple daily was really, in many ways, the headliner of the leader of, and I will just say, finally, before I turn it over to you, Sebastian, I've told you privately, I'll say now publicly, that one of the most, poignant Moments I've had as a democracy scholar was hearing your father speak here at the Hoover Institution, and, he was asked, I actually don't remember whether it was publicly or privately.

Why are you going back? You're facing probable imprisonment. He knew what he was looking at. And, the answer he gave is the answer people saw, [00:11:00] in that film. And we'll let you elaborate on it and, tell us how he's doing and what we can do.

Sebastian Lai: Sure. thank you for coming. And, thank you very much, Larry, for organizing this and making this possible.

just to answer that question first, in campaigning for my father over the last few years, campaigning for his release, you end up reading a lot of, things about him and watching a lot of interviews. And, I came across this quote that, he said to CNN, About 15 years ago. And, it, it essentially says, that he believes that you can't have dignity unless you have freedom as a person and therefore campaigning for democracy isn't political.

it's a moral duty. so Hong Kong has always been a litmus test of how China views the, rights of the West essentially, or [00:12:00] of democratic countries, not just the West. Sorry, obviously Japan is also, democratic. and. It's worth noting that my father has been campaigning for democracy.

As you could have seen, see in the video, for the last 30 years, gentlemen's square was a real turning point for him. He started Apple daily, and, they've just been, calling them out, calling the government out on corruption, telling truth to power for the last, three decades.

What's really changed is, is, why we're here, is the passing of the National Security Law. I still remember in the, 2014 protests. we were watching TV as a family. Dad wasn't there. Dad was at the protest. And suddenly on the TV, there was breaking news that Dad had been attacked.

someone had thrown some substances on [00:13:00] him and I still remember to this day we were all freaking out because, we couldn't contact him, and suddenly the door slams open. This is a horrible smell. And dad just looks at us, he's covered in pig entrails, and he just smiles and says, I guess I gotta take a shower.

And, And that's how he lived for the last 30 years. He, rolled with the punches. we, he's had death threats, assassination attempts, a house has been fired, firebombed a few times he's had to sell his, business Giordano because of his journalism and the journalism of his newspaper. but he never left.

He always, stayed and he always, woke up every day and did the work. The reason why he's now behind bars. is because of the NSO. It's a very deliberate decision by the Hong Kong government to weaponize their own legal system. And [00:14:00] so my father has been behind bars in the last, three years.

And, there's a lot of, there's a lot of hints that you could get from, what Hong Kong is now by, by the style, by how he has been, persecuted. when he was first arrested, A few months after they raided his newspaper, they send 500 people to raid Apple Daily and arrested his colleagues as well.

and then a few days after they, actually to this day, they will still claim that they have free press. And I think this is one thing that we have to know about Hong Kong. Hong Kong used to be a place where, where in order to protect its, sanctity as a financial center, they had all these freedoms.

They had the press freedom, freedom of speech, the rule of law, and bit by bit in the last five years, all these institutions that made Hong Kong, [00:15:00] great, that made it a place where human capital could flourish, have been broken down one after another. Now, The cases that were leveled against my father, one of them is, he got 14 months for that.

So my father has been in jail for the last three years, but, he served a 14 13 month sentence, for attending a, Tiananmen Square vigil. He, lit a candle and said a prayer. And, before that he got more than a year. this is, especially important because, Tiananmen, Hong Kong was the only place where you could celebrate Tiananmen Square, in any Chinese territory.

And so not only does it send a message like this, commemoration of these brave [00:16:00] people that were rolled over by tanks and in China, they can't be commemorated anymore. This, part of history has been erased essentially. Not only that, it also tells you that, we could get you on, on, on anything and it doesn't have to be, it could be something that you've been doing for the last, 30 years.

sorry. Now, what is currently happening is, he's going through his, national security law trial. he stands a maximum sentence of, life imprisonment. he, there's no jury. there's three, government appointed judges. and the, chief of security of Hong Kong, has boasted, that it's a hundred percent conviction rate.

if you need another proof that's a police state, that's a pretty strong one. [00:17:00] so my goal is to free my father. And in order to do that, we have to shine a light on what Hong Kong is doing to my father and the 1, 800 political prisoners that are behind bars and the unfair persecution.

Hong Kong still wants to be a financial center. and in order to do that, it had, it needs To have all the, freedoms that I outlined before. Because otherwise, Hong Kong has no natural resources. we have good food, fish, and I think that's basically, and a port, I think that's basically it. it's a rock without, without, the guarantees that you could do business there, unencumbered.

And yeah, my goal is to shine a light on that and to put pressure on the Hong Kong government and to tell them that, the world is watching and you can't keep persecuting [00:18:00] all these people without, without very real consequences. Thank you.

speaker: Thank you.

Larry Diamond: we'll want to ponder more. What of a practical nature we can do. But thank you for starting us off, Sebastian and for your devotion to your father and your devotion to Hong Kong. So next we turn to Ambassador Cunningham.

James Cunningham: Thank you, Larry, and thank you all for coming and for your viewers for joining us.

let me just say a brief word, not about exactly what's happened in Hong Kong, but why it is that we should care about it. when I arrived in Hong Kong as Consul General in 2005, Hong Kong was in a very, optimistic period. [00:19:00] it was the freest Chinese, city, in the world. It had very many valuable attributes, attributes that it was bringing to, bringing China and international commerce, finance, bringing that together, developing projects, such as joint education, We did a lot of work on anti pollution technologies and things like that.

And the future looks, I wouldn't say optimistic, but it looked hopeful that Hong Kong could achieve the kind of status over time that I think it was, Embedded in the joint declaration from the beginning, which was that over time, Hong Kong and its liberal values would become a magnet for China over time.

And there were a number [00:20:00] of people during that period that hoped that would be the case. And there was a lot of discussion about this in mainland China as well, not just in the U S and the international community, but in China as well, looking forward to a time when it's thought that maybe.

Restrictions on the mainland would loosen as they were, as China became more engaged with the international community and the Chinese people became somewhat more optimistic, I think, about what their own future prospects might be as they were clearly becoming, wealthier and their society was developing that part of it, the development of the economic development of the society worked.

Better than I think anybody could have imagined when I was in Hong Kong, China was growing at 12 13 percent a year that created lots of problems. But obviously, the direction was going in the right way. So the aspirations that [00:21:00] people like me had in that period was to see if China could develop into what one of our folks called the responsible stakeholder in the international community.

Unfortunately, that didn't pan out. So we have the situation that's developed over the last four years or so, which you all know. And we all know. so why should we care about that? Why should we care about what happens to Jimmy Lai, the 1800 political prisoners that are now in Hong Kong jails? And that number is growing and what's happening to Hong Kong itself.

I would say apart from the moral justice of it and the commitment that I personally feel because I I loved Hong Kong actually, and Jimmy Lai is a personal friend, as are others who are sitting in jail now. I would submit that the reason that the, that [00:22:00] we should care about what's happening in Hong Kong is not just over morality and justice, but it's over the differences of, vision of society that are playing out more broadly across the world, and are epitomized by the contrast between That's come to the fore in Hong Kong itself.

And that is of course, the, the, competition between liberal values that embody, include rule of law, free media, freedom of thought, freedom of behavior. Democracy or at least aspects of democracy. Hong Kong was not a democracy. It never was, but it had aspects of democracy. But what made it fundamentally different is that it had these, it was based on these liberal values.

And then you have the other vision of the future that is embodied in the steps that the communist party and Xi Jinping have taken in Hong Kong, which have brought it down. So [00:23:00] if you want to see in the real world, What Xi Jinping's vision of the future is in China, in his region, in Hong Kong, and wherever China can establish its, its influence and dominance, you have only to look at Hong Kong.

and that what, that's what I think is the kind of strategic importance from our point of view, as people who support a world based on those liberal values, as opposed to a world that is based on. a liberal values on the contrary vision. So there are in those invited embedded in those values.

There are two very different competing visions of what order is. And I think this is what Jimmy himself stands for. There is a first vision of order. Which is based upon the premise that you order a society around the proposition that it should enable an [00:24:00] opportunity, offer opportunity and freedom for individuals to develop themselves, to develop their economic prospects, to develop their society in a peace and sustainable way.

That's one vision of order. The other vision of order, which is the one that now is being imposed upon Hong Kong, is the kind of order that is based upon Not rule of law, but rule by law and on political control of all the means of expression so that the state creates the framework in which its people operate.

Obviously those are two very fundamentally. Different visions, but that's the struggle that's taking place on the ground right now in Hong Kong And it exists more broadly in other parts of all the other parts of the world where you have conflict now And you in some body than Vladimir Putin's view of the world and in the view of other autocrats [00:25:00] large and small throughout the world That I think is really the struggle for this century.

And that's why I think Hong Kong matters and why we owe it to ourselves, as well as to Jimmy Lai and the 1800 political prisoners and the people of Hong Kong to stand up for them and make clear that we're willing to do what we can to make that kind of life, that kind of vision more difficult and, encourage a realization that the way forward for China in the end.

is to release the political prisoners and to cease the repression in Hong Kong and allow the restoration of some kind of civic space in Hong Kong for what might be a better future for Hong Kong and for all of us in the coming years.

Larry Diamond: Thank you. Thank you so much, Jim. Tempted to note that, [00:26:00] you started as consul general in, Hong Kong right after George W.

Bush gave that remarkable second inaugural address where he spent the whole inaugural address. Making some of the points that you just made about what the struggle is and what the U. S. stands for. I had nothing to do with that.

James Cunningham: I had nothing to do with that.

Larry Diamond: you certainly defended it well in the United Nations and in Hong Kong.

And we thank you for that. Sherry, you're next.

Cherie Wong: So perhaps I'll take us to the very beginning in 1997. I was two years old. My family decided to move back to Hong Kong. There was a thought of maybe we could prosper, under the rule of the People's Republic of China. But when I was growing up, I had one question that no adult in my life has been able to answer.

And I doubt anyone of us here can answer it. What happens after 50 years of one [00:27:00] country, two system? What does that mean? And I remember people tell me that, oh, it's a, it's not our problem. It's a you problem. When you grow up, you'll figure it out. And so when 2019, the protest movement started, it was very clear to me what I needed to do.

I needed to organize. I needed to get involved. Not only in the protest movement, but also in my home community in Canada, doing political advocacy to talk to the government of Canada about the future of Hong Kong and fighting for a democratic future, ensuring that Canada as a middle power, not only As one that has very close diplomatic relationships with Hong Kong, but also as a middle power to facilitate conversation to talk about the future of Hong Kong.

So I founded Alliance Canada Hong Kong, a grassroots group, made out of Canadians from all across our coasts. And months after we started our group, [00:28:00] the talks of national security law came to our attention. And. I remember having this very grim conversation with my organizers and volunteers, and I said, who has hope to go back to Hong Kong to visit your family members?

And frankly, a lot of them put up their hands and said, yeah, I have, elders back home. I need to go home, take care of my family, my parents, my grandparents. And then I had that very frank conversation and said, if you plan to do that, you will not be a part of our core team organizing. I will reject your participation in our organization.

And I understand that was an act of self censorship. And I am actively censoring those who are in my community, who are Willing to participate or wanting to put their labor in to create a freer Hong Kong. But why did I do that? I think that answer becomes very clear today. I wanted to protect my community members.[00:29:00]

On July 1st, 2020, when the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region made it clear that they will not tolerate political views that do not align with Hong Kong and the CCP's political interests, it was clear and expected that they target political opposition. The broad spectrum of pro democracy politicians were the first to go.

The crackdowns continued, It became any local voices that offered a different point of view from the CCP. It was social workers, lawyers, teachers, journalists, students, and labor activists. The space for civic engagement practically disappeared overnight because of fear. The NSL will apply to them and that they would be held indefinitely in jail.

And that is exactly what happened. And these political prisoners aren't there because of political crimes. Their crimes [00:30:00] are simply because their viewpoints are different than what the regime allowed. As mundane as a social media post, the possession of a sticker will get you a NSL charge. And the white terror that spread, the fear that your friends and family could report you, that saying the wrong thing to the wrong person could land you in jail, that was the society that my grandparents came from, that they survived from, and that they said, watch what you're saying, because your neighbors are listening.

That became a reality for Hong Kong and Hong Kongers. And as a result, the Hong Kong society crumbled, not only because of the political crackdowns that started with media organizations and political parties. It continued to crumble. Our social support systems, some of which were founded to support our protesters, folks [00:31:00] who gave legal aid, who gave mental health support, who provided community to people who felt alone and hurt by the government's actions.

That continued professional bodies where lawyers and accountants, educators and social workers come together. The governance boards of these professional councils were filled with pro Beijing supporters. It was a very clear message that no matter what you do, no matter your profession, what your work is, as long as you align with Beijing, you'll be allowed to do it.

And the moment you speak out, you won't. And of course the crackdown continued with NSL. They started to reform the educational curriculums. Whitewashing history, rewriting history, rewriting facts favorable to the regime. And I don't want to dismiss the important work that is being [00:32:00] undertaken by those who are still in Hong Kong, because there's still people fighting back, operating within this red line that was created by the national security law and subsequently the article 23, but that red line is vague.

It moves around depending on who is in the room. With Article 23, it became very clear that Hong Kong's position is to make any form of dissent illegal, and both national security law and Article 23, has no consensus on what is and is not illegal, and I still remember the specific pro Beijing politician is She was sobbing outside of the Hong Kong liaison office because she wrote this letter to the Hong Kong liaison office asking them to clarify where the red line is.

What is the clear, what is The national security law and [00:33:00] Article 23. What are we allowed and not allowed to do? And she stood there alone, holding this envelope, shaking and in tears. And I'm talking about a pro Beijing politician who is sobbing in fear of not knowing where the red line is. Of course, I wouldn't know what it's like to be in Hong Kong.

I'm an overseas activist. I've always been. and I think it is my responsibility to speak and to provide analyses where I can and As an overseas activist, I understood the National Security Law's extraterritorial laws and clause as a warning. Those who are overseas and has opposition towards the Hong Kong government will suffer.

And on the day the National Security Law came into force, I published a statement to say that I will never return to Hong Kong or the PRC, and that I will [00:34:00] never be willingly entering to those territories. Because the one fear that I had was that may be irrational, but I may be kidnapped and reappear in China one day.

And that's frankly not that irrational when you have heard many stories of dissidents who have experienced exactly that. When Article 23 came into play, It was a heavy handed change. It was very clear that not only Hong Kong, but the People's Republic of China, thinks it's an overdue national security change.

But from my own perspective, it changed very little. I made a joke with some of my friends. It's a very dark joke. I said, let's go through this legislation and see how many claws I have broken and how long of jail time I would get just as a thought exercise. And my friend just stopped me and said, sherry.

Don't even. You would just be held indefinitely until you die. And I [00:35:00] said, you're right, actually. there goes my thought exercise, no longer needed. It's very clear that they have legalized transnational repression. They have made it possible for them to apply their laws, no matter where we are.

And it's simply an affirmation that our work overseas is more important than ever before. We're speaking and we're providing analyses for those who are in Hong Kong who are unable to do and afraid to do I understand that transnational repression has come into the political discourse in the last few years, but I also want to give credit where it's due because it occurred and it started happening long before I stepped into this activist space, and it will occur long after I leave.

Beijing first initiated transnational repression as a form to suppress the voices [00:36:00] overseas as they cracked down on Tiananmen Square student movement. They realized that the overseas community has power to change the world's perspective on Beijing and they felt threatened. And that's why they engage in transnational repression, and that's why they try to silence us, despite we're an ocean away, living in a liberal democracy.

but I'm sorry to say that they could throw whatever law at us, and we will continue to speak out, because I think we have a commitment, not only for democracy and for a future where we could be liberated, And have the ability and the freedom to choose the future for Hong Kong, the right to self determination, but also because of our friends and family who are wronged, who continue to survive the violence that are, led by the Hong Kong government, as well as the Chinese government.

I'll wrap up here. Look forward to your questions. [00:37:00]

Larry Diamond: Thank you very much.

I know Sophie.

Sophie Richardson: Thanks. This is an especially challenging group in which to go last. but maybe I'll just offer a couple of thoughts about how we got from a world in which Hong Kong people were guaranteed a high degree of autonomy. and in which one country, two systems was supposed to prevail for rather longer than it has.

To one in which even just in the last week or two, we've observed the Hong Kong government ban glory to Hong Kong. I'd be happy to sing along if anybody else would like to join. I'm not a very good singer. but to doing things like imposing bounties on activists outside the country, and imposing laws that are.

So wildly intention with the Hong Kong government's obligations under international law. I think it's important to point out that, by [00:38:00] virtue of the basic law, Hong Kong was and remains a party to the international covenant on civil and political rights. So I get a little bit frustrated when I hear people talk about Hong Kong now, as opposed to 10 years ago, or Hong Kong versus the mainland, as opposed to what Hong Kong people are entitled to.

No matter who's in charge. Because that's a very high standard on one that I think millions of Hong Kong people have made abundantly clear. They care deeply about and I was given the task of trying to summarize international responses to 28 years of threats to democracy in Hong Kong, which is a little bit of a challenge.

But I think maybe the short version of the story is to say that. Most democratic governments that engaged on this issue tended to regard the various threats as idiosyncratic and not part of a larger pattern or an expression, particularly once Xi Jinping came to power, [00:39:00] of the pathologies of that regime.

many people for some time defensively, I think, really clung to the idea that one country, two systems Would survive and tended and treated Hong Kong differently from the mainland government. But I think especially after, excuse me, the protests in 2014, were really met with, disdain and hostility by the Hong Kong government.

And we started to see, for example, the inability to hold Hong Kong police accountable for, abuses against protesters. I think the signs were very clear. That it really had become one country, one system, and I think most democracies were unwilling or unable to adjust their responses. I think that was largely a function of the international business community, which is very well entrenched in Hong Kong, pushing governments not to push Beijing.

we could [00:40:00] have a long conversation about whether that was for fear that doing so would make things worse. I will certainly never forget the full page ad that the big four accounting firms took out in the South China Morning Post, discouraging peaceful protest, which I thought was a particularly bad sign.

the responses from governments were really quite, for the most part, Perfunctory, there would be statements about particular arrests. There would be statements about clearing protests one of the requirements set out under the the central british joint declaration has the uk foreign office Publish a six monthly report on hong kong.

I can't remember how many of them now in total There are I have actually read them all and in a way they are a fascinating and quite meticulous You Account of all that has gone wrong and [00:41:00] remarkable in that nobody did anything as a result, these and for the last several years, these most of these reports have concluded with.

I'm not gonna get the exact sentence quite right, but a statement that Hong Kong authorities continue to be in a state of noncompliance. With the Sino British joint declaration, and I'm guessing that language really doesn't cause Xi Jinping any heartburn. And I think it's, one, one pro tip, I think, to take away from this whole experience is don't sign a treaty or any other kind of legally binding agreement with the Chinese government that doesn't have a redress clause, as the Sino British joint declaration does not.

a number of governments, most notably the U. S. Have taken steps in recent years to do things like impose sanctions or visa bans, to grant people asylum. Not nearly fast enough, in my view, and not nearly enough people to call for the releases of political prisoners. but there's largely been an unwillingness to challenge [00:42:00] Beijing in a meaningful, consequential way.

I do want to give a little bit of a special shout out to some of the UN human rights experts, not, let me be clear, the Secretary General, for some exemplary work both in calling for releases, but also in reviewing the Hong Kong government's failure to comply with its obligations under international human rights law, because I think those are some of the analyses against which we're best off, assessing.

all that's really gone all that's gone wrong and all that Hong Kong officials continue to get away with. I just want to offer a couple of quick thoughts about what in these circumstances governments can actually do, because I think it's both unconscionable and unstrategic to abandon an extraordinary community of people who have fought so clearly and so peacefully in defense of their and their community's human rights.

First of all, I think there's a lot of room to leverage, the Hong Kong government's interests in economic privileges for, among other [00:43:00] things, the releases of political prisoners. For Jimmy, for Joshua, for Chow Hung tung, for Lei Chuk yan, for Albert Ho, we could sit here and probably name all 1, 800 Of the political prisoners who were considered community figures 10 years ago.

Now they're considered political prisoners. And that's that. I think there's room to bring a lot more pressure to bear on Hong Kong authorities to release those people. Second, I think there's a lot of room to engage for democratic governments to engage with the broad cross section of Hong Kong Democrats.

And Democrats with a small B. inside Hong Kong as possible. This is now much harder to do because the national security law and outside as desirable to talk about what people want and to see what space they still see existing inside Hong Kong and how best to try to protect that without complicating realities.

In my world, secretaries of state should give as much status To people from [00:44:00] exile and dissident communities as they do to the foreign ministers of autocracies, and I think a failure to do that is a missed opportunity. I think there's a lot more work to do in helping people who want to get out in different ways.

Sometimes it's people seeking asylum. Sometimes it's more sort of regular paths to resettlement. People need employment. People need legal status. These two are soluble problems. And then last but not least, I think the Hong Kong government's performance on human rights has to be assessed relative to international human rights law, not relative to what's happening in the mainland.

Often you'll hear people say, isn't Hong Kong still better than what's happening in the mainland? That's not the metric we should be operating by because that just lets Xi Jinping continually lower the bar. And I think Hong Kong people have made very clear that they know their rights and they want them and they'll defend them.

I'll stop there. Thanks.

Larry Diamond: Thank you. Before we go on,[00:45:00]

could you, Sherry, or you, Sophie, or you, any of you just explain to the audience, the content of these two, obnoxious provisions, the national security law, that was adopted on June 30th, and, passed, through a ledge code that had been itself. Reformed and I would like you mind if I mentioned that you're here.

we have a member, a democratic member of Hong Kong's, legislative council elected from the functional constituency of the digital technology sector. One of the few that held to democratic aspirations, from the last Hong Kong legislature that had any fragment [00:46:00] of democratic representation, really.

That's Charles Mok. We're very happy to have him here as a visiting scholar at Stanford. So do either of you want to tell us what the national security law and then Article 23, which was imposed just very recently, you know what they do, what they provide for

Sophie Richardson: very briefly and others should chime in.

These are a pair of laws that purport to protect national security. by prescribing certain behaviors and explaining what the legal process will be if you violate them. for example, there are now, restrictions on certain kinds of speech. There are restrictions on certain kinds of behavior.

All of these are wildly intentioned, again, with Hong Kong's obligations under international law. But essentially, these laws criminalize free speech. They criminalize the right to assembly. There and they set out very [00:47:00] harsh penalties, for violating these provisions. Now, it's actually hard to explain these because the law itself is so vague, which is by design, right?

Because if you know that you could potentially get 10 years for violating, a law that says you can't insult the authorities or that, to engage in certain behavior is a threat to Hong Kong authorities, but you don't really know what the actual behavior is. You're going to change your behavior, and you're really going to err on the side of caution, most worrying in some ways, from my perspective, and others will certainly have different views, is that the national security law sets out a separate apparatus to try national security crimes.

And in a territory that is legendary for having a highly trained, independent, professional judicial system, the idea that there are now national security courts, the judges which are appointed [00:48:00] by political actors to And that place considerable limits on your right to the council of your choice, for example, in all of the standard due process that has for a long time been afforded to defendants under internet under Hong Kong law is now all set aside in national security proceedings.

So that's a, that's my very brief summary, but others might want to add to that.

Larry Diamond: You want to say anything more about how you perceive it and experience it, Sherry?

Cherie Wong: yeah, perhaps I'll speak to the legal processes, a little bit. I think most Folks who are charged under the national security law has been denied bail, and that's on purpose.

like Sophie said, the law is meant to be vague, so that it could apply to anything and anyone. And that red line, like I said earlier, moves depending on [00:49:00] who you are, what status you hold. And the ability to deny bail also serves as a deterrent for you to get legal representation. I believe under The, new article 23, you now, do not get a choice of legal representative as well.

So I think the best way to describe it is legalized repression. They have legalized ways to repress your political difference. They have legalized ways for you to be repressed by the legal system. It is no longer rule of law and does not apply equally to people who are in Hong Kong

Larry Diamond: and, not to put too fine a point on it, but if you're a Hoover fellow or Stanford professor, No kind of life connection to Hong Kong, except that you have, embraced the pro democracy movement, denounced what China has done, and lent support, [00:50:00] to, Democrats at risk or imprisonment there.

Are you at risk yourself if you visit Hong Kong?

Cherie Wong: Likely, I dare say those of you who are in the room are already in violation of the national security law and article 23. I apologize.

Larry Diamond: I just want to assure everyone the cameras point this way today and not that way.

Sebastian Lai: yes, go ahead, Sebastian. Yeah, just to, elaborate more on that point. the, the, what constitutes a national security, charge now, after Article 23 is also open to interpretation by the chief executive. so essentially he decides if, what you say to him is, constitutes a national security charge, it's, extraterritorial.

as you mentioned before, everything we do here is, it counts towards that. I don't know if you're in space, but I [00:51:00] think it's, they might get you for it anyway. there's no presumption about, or at least the holding period of someone arrested under the national security, it used to be 48 hours.

in, in every single, common law jurisdiction, it's, around that time and now, I think it could go to, weeks. And, if it's an NSL charge, they don't need a warrant. they could just go in and arrest you. And in fact, when the national security law first passed, I remember these sort of heartbreaking stories about our, our, a lot of our reporters staying up until five in the morning, because that's when they knock on your door to, tell you that they, they need you at the police station.

and actually the other point I wanted to make, about this NSL, but actually, a broader point about, anybody of Chinese descent that holds a, a, foreign passport. my, [00:52:00] my father's a British citizen and he, essentially the moment he landed in Hong Kong, when he was 11 was the first time he ever had papers.

so he never had a Chinese passport, but in this case, and in the case of many others, they will treat you as a, as a Chinese national, even if you never had held a Chinese passport, as long as you are of Chinese descent, and I believe 20. 3 percent of the Bay Area, or at least San Francisco, is of Chinese descent.

they will trial you as a Chinese national, and, they will deny all consular access, to you. So that's something that's worth noting. There's, a, belief for some reason, by the Chinese Communist Party that, all person of Chinese descent belongs to them, and that's, It's completely false, but it's hugely problematic, and that's how these people are tried at their label as traitors or whatever it is, even though [00:53:00] democracy, I don't see how you betray your, nation by believing in democracy.

Larry Diamond: Thank you. Yes, this was a point we tried to make in our original publication of the project on China's global sharp power that is one of their major forms of. pernicious sharp power projection is to regard everyone of Chinese descent as a Chinese national owing unquestioning loyalty to the motherland and therefore being a fair target for the long arm of not just repression but intimidation and threatening of family members still in the mainland and so on and so forth.

A couple of things. First of all, if you have any questions, you'd like to ask if you could write them out, and pass them to the, [00:54:00] inner aisle. we'll collect them. Keep an eye on them. And then, anyone want to comment further on this before I ask the next question? Go ahead, Sophie.

Sophie Richardson: Larry, I just want to add that, it's interesting to me, especially given.

That Hong Kong is known as a global financial center. it's a hub for all sorts of businesses. It never one aspect of the national security law that I thought never really got a great deal of attention is a provision in the law that clearly states that companies. Can be entities that violate the law.

And, we know that you can pick up a newspaper here anyway, and see that, from business press that not insignificant numbers of companies have moved to. To Seoul, to Tokyo, to Singapore, often offering up publicly some other explanation for doing that, that it's [00:55:00] about quality of life, that it's, nobody has explicitly said that it is in response, that those relocations are in response to the national security law.

but I think companies have to explain a little bit more clearly, how they are mitigating risks. To themselves to their employees. one of the reasons that we saw so many media outlets close so quickly was because they couldn't control for the risk to staff members of being accused of violating the N.

S. L. And I think that's a that's one thread for all of us to pull on more.

Larry Diamond: Great. So I'd like to look back a little bit Mhm. And then, we can look forward and talk more about the policy realm. And so I have a question for you, Jim. you arrived there, [00:56:00] at a more hopeful time. You mentioned Robert Zellick's aspiration and that famous speech that we envisioned and hope that China would become a responsible stakeholder or deputy secretary of state.

You arrive. what, roughly eight years? after the handover in 1997. So during those years, 2005 to 2008. What did you imagine might be possible for Hong Kong? And what did we, the United States government, imagine that we might be able to help the people of Hong Kong and the authorities of Hong Kong evolve toward or nurture along?

James Cunningham: thank you for that. Because it's, in my view, it's a tragedy that events have probably should have been foreseeable, but it's a tragedy that events have, occurred as they [00:57:00] have, because it was, let me just. Answer your question by saying, I did a lot of public speaking in Hong Kong when I was there, including at every opportunity I could get to pro Beijing groups, the Hong Kong conservative groups.

And when I met with them, the argument that I tried to make was, in the context of that time, That the future of Hong Kong and China should be seen as not antithetical, but as converging over time. And that it would be in Hong Kong's interest to serve as a model for China of how different views of society could be accommodated in a way that advanced joint, prosperity and personal achievement, increasing possibilities for education and healthcare, all the things that the.

Population in mainland [00:58:00] China was starting to demand as the Chinese economy was growing and his economic development was taking place, the cities were rapidly becoming more and more middle class and the Chinese government faced the challenge of lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty in a way that was Inherently, in some degrees, chaotic, and what I tried to argue is rather than, seeing democracy and freedom as inimical to Chinese society, they should find ways to try to bring elements of it into Chinese society, and Hong Kong could serve as an incubator for that.

And as I said in my early remarks, At that time, in those years, there were thoughts in the mainland, in academic and some political circles in the party, that kind of experiment could [00:59:00] be, could begin to develop at local levels in advanced places like Guangzhou and Shenzhen and other places. And from a very kind of local level of, district council or whatever, however they could create it.

And What I tried to do and what the, what our government tried to do was encourage the thought that we could all advance together. So rather than the discussion that we're having now about conflicting societies as a power emerged, this debate was taking place then, by the way. Also some, American, Academics, think tank types, policy types, were already writing about the danger to the west of the emerging China.

And the Chinese. Seeing this that I forget the name of the gentleman who wrote it, but there was a very famous piece [01:00:00] done by a Chinese think tank that argued that no, all the boats needed to rise together. And the West should not be afraid of a rising China. That would, the task was to bring those aspirations together.

And that's where the responsible stakeholder and that kind of aspiration came together. So that contrast of use of the future was already taking place. But what we as a government and, As what I was trying to do was to encourage the, former, more, more optimistic view that we could find a way to manage that kind of development over time.

And that in the promise for Hong Kong was for 50 years of this kind of evolutionary future. And that was not a deadline, by the way, That was a capture of a period of time. Hopefully that development, that parallel development of two systems would continue beyond that 50 [01:01:00] years. If the, political will were there on the mainland, I don't have any kind of crystal ball, obviously, to know what.

What Chinese leaders were actually thinking during that time. but they were certainly trying to create the impression that they wanted to allow time and space for our relationship West and China relationship to develop that Hong Kong was an important part of that. They were not obtrusively intervene.

They were intervening, but they weren't obtrusively intervening in Hong Kong at the time. You never saw anybody from the central government or the PLA. There was no parallel security apparatus or any of that stuff. They were operating behind the scenes. They were harassing Jimmy, and things like that.

they were clearly following me, when I was meeting with, pro, pro democracy types like Jimmy and Martin Lee and Cardinal Zen and going [01:02:00] around to the political parties and that sort of stuff. But it was, it was, low key and it wasn't, it wasn't obtrusive because they were trying, at that time, they were trying not to scare people off.

That shifted, in my view, that shifted after they, In my time, the whole argument was about how universal suffrage was going to come to be, and it was all focused on how, how the chief executive was going to be selected or elected. And I think my perception is that the Chinese, communist party's view of this started to change when they made an offer that would basically have allowed them to approve candidates to run for election for chief executive in Hong Kong.

And the. The democratic force, the parties and forces in Hong Kong rejected that offer. I'm not going to opine on whether I think that was a mistake or not. That's history now, [01:03:00] but I think that's when the view of the CCP in terms of, how they regarded this in Hong Kong, started to change. And then it's pretty clear to me that in 2014, after the umbrella movement, and after the, after the, another.

Factor that I credit for this changing scenario is the ineptitude of Hong Kong's own Politicians to manage their own political problems Which came to a head in spades in the anti extradition In the introduction of the extradition law and their inability to manage the protests afterwards but that started I think in 2014 15 when they were Politically incapable of bringing together a process that maintains some kind of political cohesion in Hong Kong.[01:04:00]

Larry Diamond: I think a little bit unconventional here, but the only Hong Kong politician is someone I'm looking at right now. you want to ask a question or make any comments about our juncture at this

Speaker Question: point? I'll start. I'm put already. But, what next, maybe to start with, what do you think about What's the future for your father?

Sebastian Lai: The future for my father, look, in, in, in doing this, you, have to keep your chin up and be optimistic, right? And, I'll tell you the reasons why I'm optimistic. In the last few years, obviously, there's been a lot of crackdowns in Hong Kong, but on the flip side, a lot of companies have also been moving out of Hong Kong.

and, economically Hong Kong is, hurting. a lot of [01:05:00] the, offices, are at, 60 percent occupancy, where, usually it was, in the high nineties. Real estate prices is going down. there's a lot of issues. there's a lot of excuses they could give.

but most people know why these issues are, these things are happening it's because, as I mentioned before, Hong Kong is, it's a rock. It's a beautiful rock is where I'm from. but again, without all these freedoms, if it's just another Chinese territory, it has no economical advantage.

there's no reason why you'd move there, instead of just going directly to, to, to China, where you'll enjoy the same liberties. and it's cheaper in China, actually, so [01:06:00] in light of that, it's, gotten to a point where, they are starting to feel the pain of what they're doing to, to the people of Hong Kong and, to the diaspora.

now whether they rationally wake up to that and realize that actually, most people don't want to, work or invest or live in a place where, you know, having pro democracy views or, attending a, vigil could, land you in, in, in prison, is up to them. I don't know if the current government, even cares for that.

I think at some point they'll have to, to, realize this and, bend to the pressure and realize that this, vendetta that they have to, towards the pro democracy camp is, it's, just, it's madness. it's destroyed, it's killed the goose that laid the golden egg, [01:07:00] but it's not dead yet.

So I think there's still an opportunity where if they let all the people out, if they, there's no going back, obviously, but, if they're willing to at least, discuss, going back to the rule of law, appealing some of these, article 23 and whatnot, and where it could still go back to, to, to what it, what it was.

And that would be beneficial to everybody. It would be beneficial to China and Hong Kong, obviously for the very simple economic benefits of it. but also beneficial to the West because Hong Kong Is a middle point. It's a place where values of democratic values and autocratic values of China could mingle and where you'd have a place where you could talk and that's no longer here.

Larry Diamond: I'll let any of you comment on. that if you wish, but I'd also like to get your political analysis of the [01:08:00] following in thinking about bringing pressure. Is there, how much autonomy is there for the government of the Hong Kong SAR to act on its own? Is, is it meaningful to bring pressure on the current government of Hong Kong?

Or is everything in the end so controlled, approved, restrained and scripted in Beijing that this is largely a fiction? I understand there's actually different views on this, at least on the margins. But maybe we'll start at the end and move down.

Sophie Richardson: It's it. Let me say it this way. I struggle to imagine that if John Lee, who is the chief executive of Hong Kong, the

Larry Diamond: former head of the police in Hong Kong, [01:09:00]

Sophie Richardson: qualified for the current role by Beijing's job description, and that if he wanted to take a particular position, say, for example, to release Jimmy, I have a lot of trouble imagining that he would not be overruled by his bosses in Beijing.

maybe, smaller scale issues, maybe there's still some latitude, but I think the reality is that decisions about serious, big, complicated issues. get made further north.

Larry Diamond: Do you have the same view sharing?

Cherie Wong: I do agree with Sophie that, the big decisions are probably out of, Hong Kong.

I say ours hand, but I do think it is meaningful to keep pressure on, on the big and small issues. The Hong Kong government right now has a very hard job to do to convince the global north that Hong Kong is still a global city, and we cannot let them win [01:10:00] that narrative. it is in the CCP and in Beijing's interest to keep Hong Kong as this facade of one country, two system, as this global financial hub, though it's no longer a global financial hub, but As long as we keep the pressure up both towards Hong Kong and with Beijing, we're able to keep facts as facts, which is Hong Kong is no longer under a one country, two system.

And I believe it is the UK's foreign secretary's word. It is, Hong Kong, Beijing is in ongoing noncompliance with the Sino British joint declaration. the responsibility of keeping Hong Kong as is, John Lee's job, how well he does it is up to him and his cabinet. I do think they face a lot of pressure from Beijing to do certain things well, and there are other [01:11:00] spaces where perhaps we could wiggle in a little bit of liberty, liberal changes, but in the end, Hong Kong's future, I don't believe it can co exist with the Chinese Communist Party.

I don't believe it will be democratic or free. Under the Sino British Joint Declaration or under this one country, two system false narrative that we've been sold for so many years, but it is meaningful to keep the pressure up. It's just, we have to be cautiously and realistically optimistic about it.

Larry Diamond: Okay, let me form the question of pressure, in a different way. this, comment, question, notes, I guess we could benefit from some elaboration of, the depiction here that, Hong Kong is hurting economically. I think you referred to this. [01:12:00] the property market is in a very deep downward spiral.

The stock market, small businesses have been failing. A lot of foreign companies have been leaving. this can't be good for John Lee and, his self image, not to mention his political standing within Hong Kong, to the extent that is something that even matters. but is there, so following from that, to the extent that's true, if you could all illuminate us on that, on the economic situation, does Hong Kong business have any, Ability to, influence things, either, in Hong Kong itself or more, more directly, in its engagement with the Beijing authorities.

Sebastian Lai: I, I think the [01:13:00] place of, obviously Hong Kong is a, was a financial center. and so the, the, narrative before was you the oping word of a, black, a black hat or a yellow cat, as long as it catches mice. And that was the position of the business. as long as they were growing the economy, they had a lot of leeway.

at some point though, in the last five, 10 years, there's been a shift of change. There's been a change in the, societal position of a business person. I think, China, decided that actually these people need us more than, we need them. and actually that's the. Position they take on a lot of different, relationship between countries as well.

And you can see that very visibly, for example, with, in China with Jack Ma, when he criticized the, [01:14:00] the, banking officials and he, disappeared for a while. you can see this, the slow shift change. So no, I, I don't think in, I don't think that the, business community in Hong Kong, has.

That much power to influence policy. unfortunately, and you can really see that there's the, obviously we're talking about the economy, the, stock market, but a lot of small businesses in Hong Kong are really suffering. I saw this report on, Bloomberg recently saying, that like the Costco in general was one of the busiest Costco in the world because everybody in Hong Kong would rather go across the border to buy stuff because it's cheaper there.

And again, if you have the same liberties there, you might as well have this sort of arbitrage. And I don't know what, I don't know what the goal is of the chief execs. I don't know why he [01:15:00] would keep going down this road, because at some point it's everybody at every single level is going to be affected.

And I don't know how you could say that he's. I don't know how anybody could argue that he's doing a good job, even Beijing. I don't know how Beijing could, would want someone like that at the head of it.

Larry Diamond: the next, question, echoes, a thought, I had as well, why should the Beijing leaders care what happens to Hong Kong? in the end, if, Hong Kong goes down and Shanghai becomes more important in relative terms, will they shed a tear? And, what leverage, do people in Hong Kong have given the heavy lid of repression [01:16:00] that's been, brought down upon them and intimidation and uncertainty of the nature that you spoke about Sherry in terms of people not knowing where, the boundaries are.

It's pretty obvious they don't want any kind of model of civic space, civic and political pluralism. Any modicum of self determination if the price is the end of Hong Kong as an arena, not just of prosperity, but of rule of law, yeah, and, whatever, so what, at least the questioner asks, Sherry.

Cherie Wong: I wrote this down as you were talking about that economic point. And I'll use Cantonese first. The intention is to keep the [01:17:00] harbor. Hong Kong is named the fragrant harbor. So to keep the harbor, but not to keep the people. And that is the latest narrative coming from state media. And that's pretty clear where they are going with this, right?

Their intention is not to keep Hong Kong. For the people or its culture. They don't care about that. What Beijing care about is the false image of reunification. And CJ King has said as much They said he said it is his duty to bring for a unification of China. And that includes Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

There's no intention to keep the cultural significance or the difference or to honor that. What he wants and what he is currently doing is bringing all of these territories into his control. And frankly, he succeeded with Hong Kong, he succeeded with Macau, and the next step is [01:18:00] Taiwan. So unfortunately, they care because they frankly care about that image of a one unified China.

They don't need to care about the nitty gritty of that. cultural significance or economic success. What he wants is that image of success so that he could be the supreme leader

Larry Diamond: of China. he is certainly that. I, time is, Running out. it's remarkable how fast it goes. I hope that will be the case for the Chinese Communist Party, too.

But we'll come to that. and before we do I have a big question I'd like to ask that's related to that. And then there's another question that we should close with. I'll ask it of each of you. But before I do. There's a very specific question, Sophie, that you might be able to [01:19:00] address. How might people help to protect diaspora activists from being reported to the mainland government?

Sophie Richardson: Well, Sherry should have a go at that one too, for sure. I do think some democratic governments have gotten, wiser about what transnational repression looks like and what it entails. forms of stalking harassment. we could take on down the list that, for example, the FBI or the British police used to characterize this kind of behavior.

I think there's still a long way to go in publicizing the kinds of reporting mechanisms that exist. you know that are now, I think, better known amongst, some sectors of diaspora communities, but not necessarily really broadly. And there's a lot of public education work [01:20:00] to be done.

There's also the challenge of figuring out how to prosecute some of these kinds of cases, especially if the perpetrators are not standing in the jurisdiction where the harassment or the other kinds of abuses are taking place. It's been good to see the U. S. For example, actually take forward cases.

The D. O. J. Has the Department of Justice has announced cases prosecuting individuals for transnational repression and certain kinds of harassment. But I think there's a lot of work still to do with diaspora community groups and activists in letting people know what mechanisms exist. Do you want to?

You've got more to say about this than I do.

Cherie Wong: I do. It's been a great focus of mine. personally and professionally to keep my community and those who I work with safe. And that's a huge ask. one of the main things that we've done is allowing anonymous participation of our participants and volunteers because many of them who [01:21:00] wish to contact their families back home who still want to maintain contact with those in Hong Kong and China.

but I think on. Various. It's a huge question. So I'll try to keep it as brief as possible. But allowing refugees and resettlement is a huge issue. If we can bring our family members and loved ones, and I'm not talking about a traditional nuclear family for us and our culture. It's about our cousins, our uncles, our aunties, our grandparents are like twice removed cousin that you grew up with.

It's allowing them to come to safety. I don't believe there is a Western country that has. Sponsorship plans that allow you to bring families with various degrees of separation over, but that would allow us to bring the people who are at very high risk over so that we could conduct our advocacy and activist work support for community members.

We're talking about mental health support folks who have dealt with severe trauma, who have relocated [01:22:00] here, who cannot access basic support to understand and unpack the emotional and psychological trauma that they have endured. Safety. It means different things to different people. It's allowing folks to have, good cyber security practice, telling them, here is a checklist of how you can practice cyber hygiene so that your, your footprint doesn't get tracked by the Chinese government.

It's understanding that some members of the community will want to stay quiet because they are so afraid that something could happen to their loved ones overseas. But I think most importantly, One of the critical ways for us to build against transnational repression is community resiliency, allowing our community to thrive overseas, having a space for us to practice our culture, our language, our traditions.

That has not been The case traditionally because most of the Asian and Chinese organizing overseas have focused on mainland culture rather than Hong [01:23:00] Kong culture, but allowing that space for us to come together as a community to be there for each other. That's what community resiliency mean to me, and for us if we have support in each other, we can come together to counter the repression that we face from overseas.

Larry Diamond: Great. That's very powerfully stated. Thank you. I will preface one of my two final questions. I'll ask them both and give you each a chance to answer either or both by saying, What I felt, when I was thinking about 1997, 50 years, what comes after? The Soviet Union had ceased to exist only a few years before.

I'm just going to be honest and saying, and I'm not sure that I will be proven wrong by the way I actually think it's still a 50 50 [01:24:00] proposition. I didn't expect them. The People's Republic of China to exist in 2047, and I'm still not convinced it will exist in 2047. So in answer to the second question, what is the one thing that gives you hope for the future of Hong Kong?

I'll just preface it by saying, don't give up on the future of China. but I pose these two questions to each of you. number one, how do we, how should we think about this deep and inescapable connection between the future of Hong Kong, and the of China? And what can Each of you say, or what do you want to say about what we might do to nudge the bigger question, which in the [01:25:00] end might be the way to change the smaller question.

And then, I will ask this beautiful question. What is the one thing that gives you hope for the future of Hong Kong? So Jim, we'll start with you. We'll go to Sophie. And then to Sherry, and I want to give Sebastian the last word in this session.

James Cunningham: Okay, thanks. somebody asked me in an interview yesterday, was I optimistic about, developments in Hong Kong in the future?

And I said, no, I learned in my 40 years as a diplomat, I learned it was dangerous to be optimistic, but I was always hopeful. And to go to your question about what happens at the end of this process, what you said, I think, is the thing that is most important to keep in mind in this kind of endeavor when you're [01:26:00] we've heard today how complicated all this is, and in all its many facets, what we're trying to do collectively as governments, I think, and as in our case, individuals is try to figure out How to deal with the problem that China causes, with the problem that is China.

there's no answer to that now. but I think the point you made about will, the Chinese Communist Party even exist in, in 2047 is exactly the point. Maybe it will exist, but it may not be the same thing at all. Maybe completely different. Maybe it'll be much worse. Who knows? But if you're hopeful.

It can be much better. So that's what I think we need to work on when we're trying to do [01:27:00] the, from the small but important thing to the big thing. The small but important thing right now is freeing Jimmy Lai and political prisoners, saving some space in Hong Kong and looking to the future. The big thing is what's going to happen with the transformation of China.

The work that I'm doing is trying to bring those two things together because I think the leverage, if there is leverage in dealing with China over Hong Kong, it's over the future of China's economy. And what role, not just what role Hong Kong plays in that, but what role can we create for Hong Kong in a situation in which the Hong Kong leadership and the Chinese leadership is trying to convince everybody in the world, there's nothing wrong in Hong Kong.

But we all know there is a lot wrong in Hong Kong. We need to strip apart that Potemkin, Potemkin village and keep reminding people, no, that's not true. The business and industry [01:28:00] is going to figure this out and they're going to vote in their own as they become more and more aware of it. But the, I believe the key to this at some point, somebody important, Beijing realizes that what they're doing is counterproductive and we have the right, we find the right way to get that message to them and realize.

So this all seems very daunting right now. But I think my lesson out of my career is you can't give up on history. You can't know what history is going to produce. It doesn't move in a straight line. And the lesson that I always use when I'm teaching or speaking about this is I spent the first half of my career working on Europe and European security and NATO affairs and disarmament stuff, dealing with the Soviet Union.

And. During that whole time, the, it was just taken as a truism that Germany was never going to be reunited. [01:29:00] Absolutely impossible. Never going to happen for a variety of reasons. And not least of which is that Europeans didn't want Germany to be reunited. That whole thing changed in two weeks because the forces of history came together in a way that nobody foresaw.

And the great game shifted. Literally within two weeks was up. It wasn't until two weeks before the Berlin wall came down that people started realizing this could actually happen. So that's my lesson is don't give up on history. You can make it work in your direction if you're lucky enough to find a way to do it.

Larry Diamond: Thank you, Sophie.

Sophie Richardson: So a slightly different take, maybe, the two big, or two of the biggest China human rights stories, of 2014 were the umbrella movement protests and the Hong Kong government's complete unwillingness to really engage, in some pretty reasonable demands. [01:30:00] from peaceful protests.

It was also the year that Xi Jinping launched the Strike Hard Against Violent Extremism campaign, targeting Uyghurs. And this was, the, thinking that laid the blueprint for massive human rights violations in that region that, have risen to the level of genocide and crimes against humanity.

And, the leadership in Beijing continues to enjoy complete impunity, for some of the most serious crimes under international law. And I think unless and until that changes, it's hard to imagine More systemic, or widespread change across the mainland. but to, connect it to Hong Kong, I will say that I don't think I've ever experienced anything like civic life in Hong Kong.

Like those words just don't capture the depth and the texture and the breadth and the scope. [01:31:00] Of the kinds of organizational life, whether it was church groups, whether it was a neighborhood association, whether it was, some sort of local community welfare association, and it's been extraordinary to watch that recreated outside Hong Kong.

whether it is a Cantonese language weekend school if it's, these incredible new organizations that are lobbying governments and. I find it fantastic watching people from Hong Kong, who've obtained citizenship in other countries running for office, right? Absolutely taking that democratic spirit to wherever they can actually deploy it.

and maybe my longer term hope is the idea that maybe someday, maybe sometime, this would be so cool to see Margaret Ng leading the team prosecuting Xi Jinping. That's, my long term hope.

Larry Diamond: I like that vision. Thank you. [01:32:00] Sherry.

Cherie Wong: perhaps you'll indulge in my radical activist self, prior to engaging in advocacy work.

I believe in my lifetime, the CCP will fall. I believe in my lifetime, Hong Kong will be free. And I believe in my lifetime, Tibet will be free. East Turkestan will be free. And that deep connection between Hong Kong and the PRC. When the PRC falls, the opportunity comes for us as the Global North, as the, global community as a whole, to enable the people within the PRC, people in Macau, people in Hong Kong to exercise self determination.