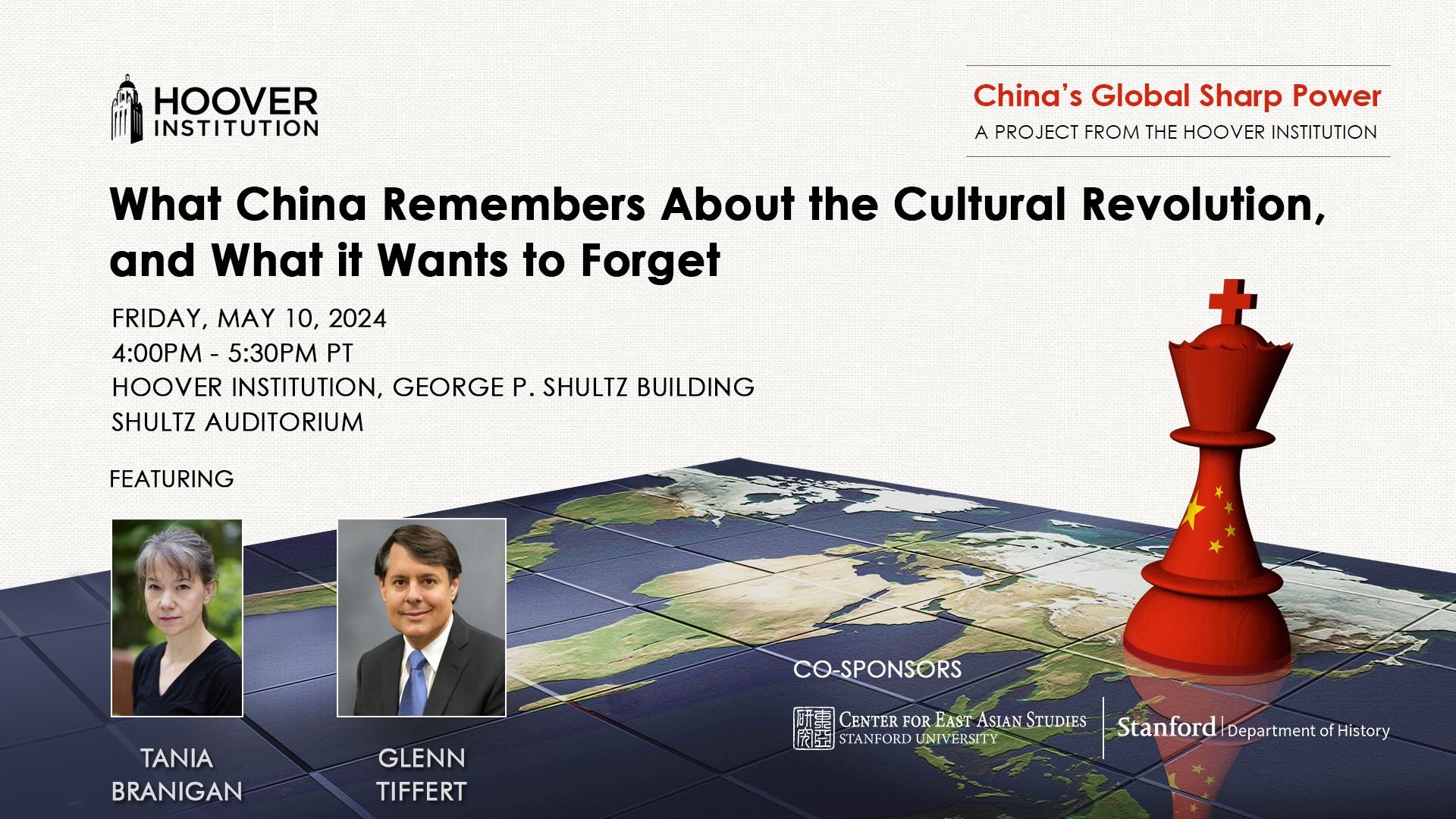

The Hoover Project on China’s Global Sharp Power, Stanford’s Center for East Asian Studies, and Stanford's Department of History held What China Remembers About the Cultural Revolution, and What it Wants to Forget on Friday, May 10, 2024 from 4:00 pm - 5:30 pm PT in the George P. Shultz Building, Shultz Auditorium.

The devastating movement unleashed by Mao in 1966, which claimed around two million lives and saw tens of millions hounded, shapes China to this day. Yet in a country where leaders have long seen history as a political tool, the Cultural Revolution is a particularly sensitive subject. How does the Chinese Communist Party control discussion of the topic? And how has an era which turned the nation upside down been used to maintain the political status quo?

ABOUT THE SPEAKERS

Tania Branigan writes foreign policy editorials for the Guardian and spent seven years as its China correspondent. Her book Red Memory: The Afterlives of China’s Cultural Revolution won the Cundill History Prize 2023 and was shortlisted for the Kirkus non-fiction prize, the Baillie Gifford prize and the British Academy Book Prize for Global Cultural Understanding. It was named as one of the Wall Street Journal’s ten best books of 2023 and TIME’s 100 must-read books of 2023.

Glenn Tiffert is a distinguished research fellow at the Hoover Institution and a historian of modern China. He co-chairs Hoover’s project on China’s Global Sharp Power and directs its research portfolio. He also works closely with government and civil society partners around the world to document and build resilience against authoritarian interference with democratic institutions. Most recently, he co-authored Eyes Wide Open: Ethical Risks in Research Collaboration with China (2021).

___________________________________

Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING] Good afternoon.

I want to welcome you all to this latest in our speaker series of book talks by leading China analysts and observers here at the Project on China's Global Sharp Power at the Hoover Institution.

I wanted to, in particular, thank Stanford's History Department and the Center for East Asian Studies for co-sponsoring this event with us.

Today, it's my great pleasure to introduce Tanya Brannigan, who writes foreign policy editorials for The Guardian in the UK.

And she spent seven years as their China correspondent, beginning around the time of the Beijing Olympics.

Her book, Red Memory, The Afterlives of China's Cultural Revolution, won the Kundal History Prize in 2023 and was shortlisted for the Kirkus Nonfiction Prize, the Bailey Gifford Prize, and the British Academy Book Prize for Global Cultural Understanding.

It was named as one of The Wall Street Journal's 10 Best Books of 2023 and Times 100 Must Read Books of 2023.

I hope you'll join me in welcoming her.

The format will be she'll give a presentation about the book, we'll engage in a little bit of discussion, and then open it up to what I'm sure will be a rich question and answer segment from the audience.

I look forward to that.

Thank you.

Thank you so much, Glenn.

And thank you to you all for giving up such a beautiful sunny afternoon to come and listen to me.

It's a great honor to speak here today and also slightly daunting as a journalistic interloper amid all of the scholars.

But one of the most enjoyable parts of my job as China correspondent and now as an editorial writer is ringing up incredibly clever people and peppering them with lots of questions.

I always think it's a bit like being back at university, but without the looming specter of loan repayments.

So it's a joy to be here.

And I'm looking forward to learning lots in these sessions tomorrow.

It also gives me an opportunity to thank all of those scholars both within and without China, whose research and insights have informed my own work on the Cultural Revolution.

As this talk is for a broader audience, I hope the sinologists present will forgive me if I cover some familiar terrain.

Although academic research has been invaluable, my primary sources in writing my book Red Memory were Chinese men and women from across all walks of life and of all political persuasions, from unrepentant red guards to those still struggling with half a century of guilt.

They ranged from retired factory workers to the lawyer assigned to defend Chairman Mao's wife, Zhang Qing, in the aftermath of the movement.

And they even included people who impersonated the era's leaders, which is why I can say not only that I've met Mao, but I've actually met him twice in swift succession.

While these impersonators didn't regard their work as kitsch in any way, they did rather underscore the fact that the Cultural Revolution seems more permissible as farce than as tragedy in China in many regards.

There are, for example, not one but multiple Cultural Revolution restaurants where you can go and dine on dishes such as party secretary aubergine, while waiters dressed as red guards sing and dance to the East is Red.

And yet, in the whole country, there's only one national heritage site relating to the era, which is a graveyard for red guards in Chongqing.

It was at one stage threatened by economic development because local officials wanted to build a theme park over it.

And those plans fell through, but then political concerns intruded.

And so by the time I went to see it, you had to gaze at it through the bars of a gate.

You couldn't go any further.

And later on, the gate was covered with a sheet of metal so you couldn't even see in.

And a security camera was installed above it because the party is not only restricting memories of the Cultural Revolution but also monitoring who is remembering and how.

In my seven years in China, I watched as memories of the movement were disinterred, revived, nurtured, and preserved by ordinary citizens, but also as they were increasingly policed, exploited, and suppressed by the party state.

In reality, the Cultural Revolution was 10 years of violence, chaos, and stagnation, unleashed by Mao in 1966 and ending only after his death a decade later.

An estimated two million people were killed or handed to their deaths, and tens of millions were persecuted for political thought crimes or accidents of birth.

And it was truly universal.

It rippled out from Beijing to the furthest reaches of the country and from the elite down towards the lowliest.

Both of Mao's assumed successors would die, but so would infants in remote villages killed because their grandparents were supposedly landlords.

The intimate betrayals were perhaps even more devastating than the abuses of power.

Comrades and friends turned on each other, husbands, sisters, even sons and daughters denouncing the ones they loved.

Many of those I spoke to wanted to talk because they feared it might one day return.

But there were others who lamented the movement's demise.

Some believed it made political reform essential, but others believed it required adherence to the status quo at all costs.

What united them was this.

While most people forgot the Cultural Revolution, these people insisted on remembering.

In one way or another, they were keeping its memory alive.

They included an octogenarian composer whose work was forged by his suffering, a son seeking to preserve the grave of his mother who was executed because he denounced her when he was aged just 17.

And there was the man with whom my research began, the artist Shu Wei-shin, who painted around 100 portraits of people caught up in the era, whether famous, infamous, or unknown.

He told me that there was one missing, which was the very first portrait he'd completed as a child.

He was shocked to learn that the teacher he looked up to was actually a class enemy, the daughter of a landlord.

And ashamed at his own naivety in his fondness for her, he drew a vicious caricature, pinned it to the blackboard, and he still remembered, as though it were that warning, how white she had turned when she'd walked into the classroom and seen it.

Because she knew what it might mean and where such attacks might lead.

And although he didn't then, he soon learned.

He was eight when the movement began.

But when he talked about his teacher, he said, of course, I was responsible.

It's only a question of how large or small my responsibility was.

And so he hoped that his work might spark that kind of reflection in other people and ultimately help his nation to move forward.

But in fact, his portraits have been shown together only once in China.

Because even under the euphemistic title of Chinese historical figures, 1966 to '76, they were still simply too sensitive.

I meant to write a story about his work and then move on, because my day job was reporting news.

And in a country that was transforming itself at such speed and when everybody was constantly looking ahead and grabbing the next opportunity, it seemed quixotic at best to turn to the past.

And yet every story I reported on after that seemed to keep leading me back to the Cultural Revolution.

A film director described how the great cultural vacuum of that time and then the sudden reopening to the outside world had shaped his work.

Tycoons described how their drive came from that era of struggle.

And a novelist told me that for her family, the Cultural Revolution had only ended the previous year.

I assumed that we'd misunderstood each other.

But then she explained that was when her father died still arguing with the Red Guards who'd persecuted him almost 50 years before.

He'd never recovered from his breakdown.

The Cultural Revolution isn't just an era that lies easily within living memory.

Many of those I interviewed seemed at times to be reliving rather than merely remembering what had happened to them.

And yet it is at once everywhere and nowhere.

The state and the people have conspired in a national amnesia.

For over time, I came to realize that personal trauma was as powerful as official repression in silencing discussion.

A psychotherapist told me that in the aftermath, you might discuss it with a stranger on the train but never with a workmate or neighbor.

And many still won't talk about what they did or what was done to them even within their families.

But the battle to define memory is happening not only between the party state and the citizen but also between citizens and even within them as people try to come to terms with their own culpability or make sense of their suffering.

You cannot make sense of the country without understanding the Cultural Revolution.

China's culture, its politics, its economically, its psyche are all deeply shaped by the movement.

It's the pivot point between socialist utopianism and the capitalist frenzy that followed between pitiless uniformity and ruthless individualism.

It destroyed not only the old Confucian ideals of filio obedience but also communist pledges of fraternity.

And yet it's a movement so complex, contradictory, so fractured, and so extreme that it's almost impossible to understand, including or perhaps especially for those who lived through it.

People often like to recall the absurdities of the era.

At one point, for example, Red Guards ordered Beijing's traffic police to direct vehicles using the little red book of Mao's thoughts because only Mao's thinking could show you the correct way to go.

And incidents like that, as much as the mob violence, can lead people to imagine that this movement was just about the zealotry and extremity of youth, Lord of the Flies with added politics.

But it was, above all, Mao's attempt to reassert his political supremacy and eradicate all opposition after the disaster of the Great Leap Forward.

His hubristic attempt to transform the country's economy at breakneck speed, forcing farmers into vast communes, led to the deaths of tens of millions in a devastating famine and was reined in by more pragmatic figures within the party.

Mao was furious and fearful.

He'd seen how Khrushchev had denounced Stalin following his death.

And he was thinking not only about his power in the moment, but also about how history would remember him.

He also saw these events as a political failure in the broader sense.

For him, the failure of the Great Leap Forward was a failure of will.

He thought his revolution had lost its way.

Purges were a feature rather than a bug of Mao's leadership.

But this time, it was different because he went outside the party.

He whipped up mass emotion and turned it against the party.

And young people, children in many cases, became his political vigilantes.

They'd been brought up to revere him and raised on ideals of struggle and revolutionary violence.

The wider population was traumatized by decades of invasion, war, and famine.

And when you have an event on this scale, a mass ideological crusade, it swiftly draws in not only political fanaticism, but paranoia and personal grudges and all these other forces and emotions.

People turned upon others to protect themselves because someone was going to be persecuted, so why should it be them?

Or they retaliated for an earlier accusation made against them or someone they loved.

It began with denunciations and attacks by Red Guards.

Teenage pupils slashed trousers that they thought too fashionable and raided homes and temples.

Relics were burned, artworks smashed, theaters closed, schools and universities shuttered.

Red Guards tortured and murdered their teachers.

And then as the movement spiraled, the groups began to splinter into factions and turn on each other, often physically.

In Chongqing, which housed munitions factories, rival groups fought not only with batons and bricks, but even with grenades, machine guns, tanks, and warships.

Even Mao concluded that things were getting out of hand and used the army to rein in the Red Guards.

And what followed was a period of more bureaucratic, but still deadly persecution, in which waves of political campaigns ensured that no one but Mao was safe.

To keep the cities calm, 17 million children and young people were sent off to labor in desperate conditions in the countryside, among them China's now leader, Xi Jinping.

Some of them never returned, and many only did so after Mao's death and the overthrow of his wife, Chongqing, and the other members of what became known as the Gang of Four, key cheerleaders of the movement.

The Cultural Revolution has never been entirely taboo, as the brutal crackdown on 1989's pro-reform demonstrations are, for example.

But the party does not want a detailed recounting of these events, still less an exploration of their causes.

Of course, no country is entirely honest about its own history.

Bizarrely, as a Briton, I was never taught about the slave trade and empire, still less that they formed the foundations of my homeland's wealth and power.

Eric Williams once observed that British historians wrote almost as if Britain had introduced slavery solely for the satisfaction of abolishing it.

It goes without saying that my education never mentioned the Opium Wars.

But an authoritarian states, of course, the controls on history are far more deliberate, explicit, and extensive, and breaches are far more severely punished.

There are few scruples about the use and abuse of history.

In China, it's long been clear that history is not a record, still less a debate, but a tool or even a weapon.

Each dynasty chronicled the one it had supplanted.

And Hu Ping has argued that for Chinese people, history is our religion.

History is a moral and political force.

The exploitation of history has been especially evident under the Communist Party.

Communism is a vote for the future, but that vision is sharpened by the contrast with the past.

The party knows that people rarely stay grateful for long.

And so almost as soon as it took power, it began to invoke the old days.

Some of my interviewees record taking part in rituals of recalling past bitterness and cherishing present happiness.

Although sometimes farmers would include the great famine in the list of miseries and would have to be reminded by cadres that past bitterness only referred to the years before the party came to power.

Over the years, the narrative has been refined and adapted.

Generations of Chinese students have learned about how foreign powers shamed China.

In his book, Never Forget National Humiliation, Zheng Wang has written about how patriotic education was ramped up in the wake of 1989.

The party's bloody crushing of the protests destroyed what lingering shreds of a claim to serve the people remained after the Cultural Revolution.

In its wake, the leadership's legitimacy rested upon growing prosperity and this narrative of national rejuvenation.

And as economic growth has slowed and faltered, and as younger generations take their parents' hard-earned advances for granted, this historical narrative has become more and more important.

Xi Jinping, perhaps more than any other leader since now, has understood the importance of history.

And under his watch, the past has been both fetishized and threatened.

His first public act on assuming the leadership was to take the rest of the Politburo Standing Committee to the National Museum to tour an exhibition about how the party saved China from humiliation by foreigners and returned it to greatness.

And within months, he'd tell officials that historical nihilism was an existential threat to it on a par with Western-style constitutional democracy and freedom of the press.

Historical nihilism is, in essence, anything that challenges the party's version of history, often what we might call memory or facts.

The power of history is that it's supposed to be immutable, graven in stone and everything is as it was meant to be. 5,000 years of Chinese history has borne the country inexorably towards its present-day triumph with no errors or diversions along the way.

And yet the reality is that history has proved immensely flexible and adaptable.

You may remember the old Soviet joke that the past is certain under communism.

It's the-- sorry, the old Soviet joke that the future is certain under communism.

It's the past, which is unpredictable.

So it is with the Cultural Revolution.

That's in part because the movement was itself so complex and contradictory, full of currents and countercurrents, so that people were victims one day and perpetrators the next.

But it's also because the narrative has evolved to meet the needs of contemporary politics.

Initially, remembering the horrors of the Cultural Revolution, or at least some of them, was useful.

The authorities tolerated the cathartic flood of scar literature, memoirs and fiction attending to the-- attesting to the suffering and violence of the era.

And they commissioned an official verdict describing the movement as a catastrophe for China.

There were show trials for Zhang Qing and other leading figures in the movement.

Zheng Xiaoping was by then in charge.

He'd been purged himself twice in the Cultural Revolution.

And his son has used a wheelchair since falling from a window while held by Red Guards.

Quite aside from personal feeling, there was a political challenge here.

The party elders who'd been purged but were lucky enough to survive needed to reaffirm that they were the ones who were the good guys.

They wanted to ensure that it could not happen again.

And they wanted to justify their turn away from Maoism.

But Deng also instructed those drafting the verdict that the aim of summarizing the past is to unite people and look ahead.

He didn't want to dwell on it.

The purpose was not to memorialize the era.

The message was not never again.

It was essentially more like, let's get this over with.

And there were always limits to what could be discussed.

Although Mao was described as initiating the Cultural Revolution, he was laboring under a misapprehension.

And others were really to blame for the worst aspects.

The vast majority of killings went unpunished.

Many of the early Red Guards who'd lethally attacked teachers and scholars were the children of the political elite.

Close scrutiny of what happened was inconvenient.

Once the initial outpouring of remembrance had served its purpose, discussing the era also became more sensitive.

The early '80s saw the backlash against scar literature.

And in 1988, a regulation warned publishing houses not to issue dictionaries or handbooks.

In 1996, scholars held an anniversary symposium.

But 10 years later, they were warned off.

The problem isn't just that well-connected people are implicated in atrocities or that the leaders who were rehabilitated had sometimes cheered on the campaign at first.

The Cultural Revolution struck at the party's very roots.

It's often suggested that the party continued to laud Mao because it could not afford a more honest reckoning with the PRC's founder.

He's China's Lenin and Stalin in one.

I actually think it's more fundamental than that.

If you allow the public to judge the past, then why can they not judge the present?

If they can turn upon their former leader, why can't they turn against you?

What's more unexpected, perhaps, is that the memory of the Cultural Revolution has also been useful to China's leaders in the longer term.

The most striking recent example has been Xi Jinping's reinvention of his seven years of rural misery as an educated youth into his creation story.

This is the one part of the Cultural Revolution that is not only acknowledged, but even applauded by the official media.

Over time, his ordeal has become detached from its roots in political fanaticism and repackaged instead as a coming of age tale in which the young hero discovers himself through honest toil, shows his grit and love for the people, and is humbled by the humanity of the peasantry.

But the deeper usefulness of the Cultural Revolution has been in shoring up the party's wall.

It was a disaster so undeniable and overwhelming that it's come to stand for the dangers of any kind of change, any threat to rigid party control.

If young people are given their head, if subordinates can challenge their leaders, then this is the result, chaos.

This understanding of the era is only possible if it's not faced full square.

It must be veiled because the party's responsibility for the disaster can't be dwelt upon.

It's a bogeyman which is all the more potent because it's shrouded, because it dwells in the shadows.

And this vagueness also allows the era to be repurposed as the political occasion demands.

Though the disgraced quasi-marist leader of Chongqing, Guo Shilai, was tarred by allusions to the Cultural Revolution, but it was also invoked to attack the student demonstrations in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong in 2014.

The message is simply that any deviation from the status quo, whether left or right, will result in turmoil, and that only the party's tight grip on society, on the unpredictable and dangerous masses, can protect the country from reckless and lethal instability.

An era of turmoil created by the party has been used to justify and buttress the party's rule.

Of course, the party's extensive censorship and intensive propaganda means that young people's knowledge of the movement is limited, and the potency of the threat appeared at times to be ebbing.

Yet a growing number of people in China see echoes of the time in the current political climate.

Now, in many ways, I think the divergences are as striking as the parallels.

It's impossible to imagine Xi relishing disruption and disorder in the way that Mao did.

Nonetheless, China's most powerful leader since Mao rules indefinitely, having seen off term limits.

There's a burgeoning personality cult.

We don't see the quasi-religious veneration accorded to Mao, of course.

But a propaganda video showed schoolchildren singing that, "Grandpa Xi is our great friend," and waving sunflowers in honor of a smile they called "warmer than the sun," just as Chinese citizens were once compared to sunflowers turning towards Mao, the red sun in our hearts.

Authorities are also fostering suspicion of foreigners and foreign influences, and the party has comprehensively reinserted itself into the hearts of parts of Chinese life it had somewhat retreated from.

The handling of the pandemic was a profound shock to many, that your life could be so closely monitored that the state could break into your home and drag you away, that neighbors were informing on you.

None of this was surprising to dissidents or activists, but to others, it was startling and felt like a return to a much darker era.

And one of the slogans seen in the rare zero COVID policies read, "We want reform, not the Cultural Revolution."

So for now, those memories persist.

And while the authorities often try to suppress the past, others are trying to recover and revive it.

Ian Johnson's recent book, "Sparks," focused on the many underground historians excavating China's recent history.

But navigating these tricky waters requires sacrifice.

For some, it may mean simply recording facts with little context.

Often, it means restricting the circulation of their work, deliberately reducing its impact.

Peng Qian, who opened the country's only cultural revolution museum, found that it could only stay open if it kept an extremely low profile.

Instead of urging people in, he just had to hope that they'd find it.

And it's since closed, incidentally.

Peng, who almost died in the Cultural Revolution, wanted the museum to prevent a recurrence of the era.

But the truth is that many in China recall it for other reasons and recall it fondly.

For some, that's simply because it was when they were young.

They relished the closure of schools and traveling around the country.

And of course, it's easier to look back with affection if you weren't at the hard end of events.

But above all, I think, this fondness exists because nostalgia is always as much about the present as it is about the past.

And so faced with rampant corruption, soaring inequality, and rapacious materialism, people harked back to a time they saw as purer, more idealistic, more egalitarian, and above all, more meaningful, where life might mean more than the pursuit of prosperity.

Guobing Yang has noticed that the mass nostalgia movement of the educated youth emerged during the mass layoffs due to the restructuring of state-owned enterprises in the '90s as a generation lost not only their livelihoods, but a whole way of life and identity.

They started to turn back towards their youth.

It's important to stress that they're not in denial.

They haven't forgotten how tough things were.

So the educated youth I met told me about the hunger and the hopelessness and the friends who died and the girls who were abused by cadres.

But they still wanted to believe that there was a purpose to it all and that they, like she, came out tougher and better people.

Others were more explicitly political in comparing the past and present, whether Red Guards who'd never lost the faith or Neo-Maoists who lamented being born too late.

They saw it as a time when workers were a priority, people could challenge corrupt officials, where culture was for the masses, and when ordinary people could be engaged in political activity.

They believe, essentially, that the Cultural Revolution has been produced because the people who suffered were often the very people, political leaders and intellectuals, who benefited from privilege beforehand and who shaped our understanding of events afterwards.

Why, for example, was it so horrifying that better off urban youth should be subjected to the conditions that were normal for rural children?

The scholar, Mo Bo Gao, was himself submitted to struggle sessions, yet suggests that the violence was exaggerated and that the constructive and creative developments of the time have been unfairly ignored.

I find his reading far too generous, but I think it's easy to dismiss the value that some find in the Cultural Revolution without asking why they locate it there.

It's true that, in general, workers and farmers were given more respect.

In Chongqing, I met with former Red Guards who described not only a time of fanaticism, but remarkably of great democracy.

There was, briefly, feverish discussion of political ideas, and Yiqing Wu has shown how ambiguous and sometimes contradictory policies from the center allowed longstanding grievances to burst into the once tightly controlled political arena.

Of course, Mao himself was sacrosanct, but the fact that ordinary workers and pupils could challenge and bring down people with power over them, however cruelly or misguidedly they did so, was revelatory for some.

Abusive officials could face accountability for the first time, and a number of workers and students offered a radical challenge to the state, demanding better conditions or rejecting attempts to re-centralize power as the Cultural Revolution evolved.

They often ended up paying dearly, but although these early possibilities were brutally curtailed, they did live on as a kind of memory.

They induced a more critical attitude to authority and a sense that dissent was possible.

The Democracy Wall movement, which sprang up in 1978, had former Red Guards at its core, and Wei Jingshun, who posted the most famous essay calling for political liberalization, had been a sent down youth who was shocked to learn from farmers about the party's role in the Great Famine.

Realizing how authoritarian political power shaped the lives of the very poorest convinced him of the need for change.

Finally, some of the most powerful manifestations of grassroots memory are unintentional, and I'm thinking here of what's been called post memory or transgenerational trauma.

Even or perhaps especially when people have not discussed their suffering, the pain of the era is transmitted from parent to child.

How can you expect your son and daughter to make sense of the world and to navigate it with confidence when all your experience has shown that the world makes no sense and is unsafe?

The result, as Elena Cherapanov writes in her work on the transgenerational legacies of totalitarianism, is that traumatic history violently intrudes upon the present, creating a sense that the tragedy keeps repeating and there is no escape.

Yet if we are not the masters of our past, nor are we simply its servants.

The great sociologist Fei Xiaotong once wrote that our memory does not record something for use in the future.

Rather, we reflect back on our past experience to establish a connection to the present.

In fact, it is very difficult to foresee what might be useful in the future.

Instead, what we need in the present is constructed selectively by our recalling of the past.

Fei was writing in the 1930s, but his words were strikingly prescient.

In recent decades, neuroscientists have established that we do, in fact, construct or create memory.

To put it extremely crudely, we are not retrieving a mental video, but are assembling it from a number of different components.

Both consciously and otherwise, our versions of the past evolved over time.

And other people's accounts tinge not only what we say about the past, but what we actually recall.

The Communist Party would like people to remember, but not very much, and to forget, but not completely.

Yet if the party takes what it needs in the present, in Fei's terms, so too do the people.

That is why the history of the Cultural Revolution will continue to be rewritten, not only by those serving the party, but by those it still claims to serve.

Thank you.

[APPLAUSE] - Thank you, Tanya.

That was a marvelous presentation.

And for those of you who heard her thoughts on this for the first time, I urge you to read the book, because there are other similar wonderful turns of phrase, paragraphs, and thoughts expressed.

And I want to pose some provocative, if perhaps even unpopular questions to pull on threads that you raised in your talk.

There is a real sense in which the Cultural Revolution might be seen as the fullest expression of phenomena that had been present in the party and periodically seized China from the origins of the party going back to the 1920s, whether it was land reform in the Jiang Xi Soviet, whether it was the rectification campaign of the early 1940s, land reform in 1947, the campaign against counterrevolution, the three anti-campaign, the Great Leap Forward.

And so there is a sense in which bracketing it out, because it remains in the living memory of people who are alive today, I think dissociates it from larger historical processes.

Are we opening the Cultural Revolution thinking about it?

How, for example, have the people that you interviewed and you yourself, through the experience of speaking to them, how has their attempt to grapple with what happened in that period changed their understanding of what contemporary China is?

Because so much of contemporary China was defined as using the Cultural Revolution as a foil, whether it was the collective leadership, whether it was economic and social liberalization, the reconstruction of the legal system.

How do we understand all of this if we begin to reopen the Cultural Revolution and destabilize the party's own narratives about it?

Yes, I think it's been extremely difficult for people.

Myself and for many of those I interviewed, the Cultural Revolution was really the apogee of Maoism.

And for the party, it's obviously important that it be seen as a diversion or a deviation en route.

Something went terribly wrong.

So it's striking, for example, that in talking about historical nihilism recently, one of the things that the party has singled out is suggesting that there's a difference between the periods before and after reform and opening, before that is Maoism in full flight and the move towards the market.

That's so extraordinary.

It's extraordinary to a point it's nonsensical, essentially.

But it testifies really to how important it is that the party has a sort of smoothness of narrative.

And that requires, as in the official verdict, it to be a mistake, a misapprehension by Mao along the way.

But certainly, I think there are such powerful threads that run through it.

For example, the composer that I interviewed was somebody who, like many of those who suffered in the Cultural Revolution, had been very devoted to the party and a true believer before the Cultural Revolution.

And yet, he now understood many of the party's impulses in controlling culture, for example, to be essentially present from the start.

So even before the party takes power, going back to the 1930s at their base in Yan'an, we see them talking.

We see Mao talking about how culture needs to be a weapon.

He needs art soldiers, that culture is a battleground.

And these ideas are carried through, right through to the present day, in fact, at their most pronounced in the Cultural Revolution, but still very evident in the way that the party controls culture, even at a strikingly petty level to us.

So yes, I think for many people, looking at the Cultural Revolution leads them to re-evaluate not only how China got there.

In other words, for many of them, it was seeing that Mao was part of the problem, even having started off from a position of venerating him, but also that it really made them re-evaluate the present and the way that the party still controlled things.

I remember one person I spoke to saying, well, it's not really gone.

It's just a time out.

And so there was this sense that the underlying forces perhaps hadn't shifted as much as one thought, even though, as you said, there'd been this incredible attempt to cage or control those things through measures such as collective leadership.

And then, of course, more recently, we've seen those safeguards disappear.

And so now we see people thinking much more about the echoes of that time.

There was a despair that struck people by the end of the Cultural Revolution that the project of new China had utterly collapsed and perhaps had been a fraud among large segments of the population.

Without trying to make an equivalence, those of us who've gone back to China in the last year after COVID have detected a similar despair, a sense that the project of China since reform and opening, that linear trajectory from home run to home run, and China is the country of the future and the 21st century has somehow fallen off the rails.

And in particular, a sense in which there's been a collapse in faith of the basic competence of the government that in some ways echoes what happened in the mid 1970s as people began to take stock of what had happened during the Cultural Revolution.

Do you see this as having implications for the future of China?

Is this just a momentary sort of gasp after COVID?

Or is there the possibility that this presents the seeds for a new awakening in China that begins to take it onto a path that perhaps is more liberalizing?

I think that's such a fascinating question because it really did feel, didn't it, like this moment where the idea of authoritarian competence was so thoroughly undermined.

I do think some of it is linked to the outside world and how much there appears to be an alternative.

And clearly looking obviously at the Trump years here, but equally in the case of the UK at Brexit and our prime minister who lasted less time than a lettuce and so forth, the idea that there is a sort of a strong alternative out there also looks pretty weak.

But I am struck, I think, within China that there's been this sort of series of disillusionments, in fact.

And I think one of the things at the end of the Cultural Revolution, it wasn't just that they'd been through these horrors.

But then finding out it was for nothing for some people was almost more traumatizing than what they'd been through.

Even victims in some cases somehow sort of justified it to themselves as they must have done something wrong.

They weren't good enough communists.

They didn't believe enough.

And then discovering that it had all been a terrible mistake, you know, that was-- it so fundamentally undermined their faith in the system, but also in their ability to sort of trust themselves.

I think there is a sort of an underlying uncertainty and lack of confidence for many people in anything being very solid or reliable.

And so perhaps it doesn't take very much for that to sort of disintegrate.

Yoojin Ting may be right that there's a nihilism that grows from that.

Well, I think what really happened, what was striking about the zero COVID and then the reaction to that was that it felt as if the increasing stringency and the increasing pressure from the state in so many aspects of life was driving in one direction.

And then the ability of the state to actually deliver was going in the other.

So there was this collision between these two unfortunate forces.

Now, you've returned to China more recently than me.

And I'm also always aware that one gets to talk to a limited number of people at any time.

I don't know where the Chinese population is, whether many of them feel fundamentally that the government's recovered the rest of the world's in a mess.

Actually, China's still doing pretty well.

There is clearly still people who do have confidence in the project.

But it is obvious that for some people, at least, there has been a real rethinking and questioning.

So let me flip the script.

Because in the book, because it's written so freshly and recently, you make the point of there is this populism around the world that sort of forces us, I think, to question our own societies and the directions that are going in.

There is a real sense for some people who experience the Cultural Revolution, including some of the people that you interviewed, in which it was a moment of liberation.

It was a moment of freedom that up until the edge of the Cultural Revolution, they'd lived through a period of time that was intensely repressive.

And the Cultural Revolution, particularly for young people, opened up possibilities to overturn status hierarchies, to rebel against their parents and teachers, to hop on trains and see the country with no responsibility, even though many of them did witness horrors that have stayed with them for the rest of their lives.

And for some people-- and there's been films made in China about this, too.

It was a moment of sexual liberation.

But of course, the flip side of that is, for many, it was also a moment of sexual violence, too.

But these narratives have been even less discussed, I think, within contemporary China.

Certainly, the narratives of trauma and suffering have circulated more widely.

And I want to ask you, do you think that this might be because, ultimately, the sense of that grassroots agency and populism of rebellion, as I think you suggested, is even more threatening to the party than anything else, that this is what Xi Jinping is most afraid of?

Mao did not fear his people, but Xi Jinping appears, too.

That's fascinating.

And I honestly don't know.

I think part of it, as well, is, as you say, for many of those who lived through it, even the people who found it liberating in many ways, they are also deeply traumatized by what they saw.

And so talking about it is difficult for them.

And they're also aware of the sensitivities of those who suffered greatly in the movement.

And obviously, it seems to be sort of desperately missing the point, in some ways, to say, oh, it was this time of great freedom, where I didn't have to go to school.

And I got to travel around the country while I was on holiday, while perhaps your interlocutor is somebody who lost a parent in the movement or whose life was fundamentally derailed by what happened to their family.

So I think perhaps for ordinary people, too, these are very difficult things to talk about.

But certainly, I mean, it was a moment of political potentialities in a way that is very difficult for the party to acknowledge and that it clearly won't want to acknowledge.

And so although on the one hand, it sort of tries to draw a line between the disorder of 1966 and the demonstrations of 1989, even though 1989 and Tiananmen Square was so fundamentally different that we were talking about large-scale peaceful protests, not a violent upsurge of political vigilantism, but there are those sort of threads.

And even though the party, on the one hand, wants to acknowledge those because it wants to tar things like the Tiananmen protests as being part of disorder, at the same time, it probably doesn't want people to think too deeply about the idea of the Cultural Revolution as a political movement rather than just as human nature being terrible and young people getting out of control.

Well, thank you.

I'd like to open it up to the audience now because I'm sure that there are great many questions, both in the in-person and the online audience.

And so let's see if we can do that.

And please raise your hand.

Peter, we'll start with you over here.

I'm Peter Michelson, professor of physics here at Stanford University.

So first of all, I want to thank Tanya for a marvelous talk and a very insightful book that I think everybody should read.

So thank you very much.

I just wanted to ask you to comment, though, about at the beginning of your talk, you acknowledged that in your education, you never heard about the Opium Wars, a lot of things.

I think that's true across a lot of Western countries.

We're in denial or not even acknowledging history.

And I'm thinking of-- and I think that provides-- and I think leaders still don't do that.

You think they should.

And how would that help in-- I'm thinking of US-China relations, how that could actually change the narrative.

I think they absolutely should.

What I've seen certainly in the UK is that it's gone in the opposite direction.

So we've actually had culture ministers saying that historians shouldn't rewrite history.

Amuse me, because I thought, what else is the act of writing history but rewriting and rediscovering new narratives?

So I feel in many ways, it's gone in the wrong direction, certainly in the UK and obviously on the right here.

Although it's important to say we have also seen certainly in Britain, there is a renewed reckoning with empire and with British involvement in the slave trade.

And you see the kickback against that and the backlash, which is very strong.

But there is-- I think young people are growing up with a much stronger sense of what the truth is.

I don't think that necessarily fundamentally resets the US-China relationship or the European-China relationship if you're looking at government to government relations.

I do wonder if it helps to reset relationships between peoples at a time when there is immense suspicion and hostility on both sides.

But I think fundamentally we should do it because it's the right thing to do.

When I asked, did you read history in school?

For my degree?

Yes.

No, no, I did social and political science.

Excellent.

Well, you're a historian, I think, by practice.

Young Young.

Thank you so much.

And actually, OK, I have a first small question.

So I was curious whether you've seen the Netflix adaptation of the three-body problem.

And in particular, as a former China correspondent from the UK, I was curious how you saw the depiction of the Cultural Revolution.

But that was really a lead up to-- my actual question is, as you also cover in your book and your talk, that the Red Guards was but one part of the first phase of the Cultural Revolution.

And so I'm curious why the Red Guards have become arguably the most prominent and enduring symbol of the Cultural Revolution when a lot of the other aspects, including the elite power structures on one hand and the factional fighting and mass executions on the other in the provinces, in the rural areas, caused far more casualties in the Red Guards damages, are somewhat subdued in comparison.

Thank you.

It's lovely to meet you because I'm a great admirer of your writing.

So it's great to know you're here.

On the Netflix three-body problem, yes, I have watched it.

I haven't quite made my way to the end.

In terms of the Cultural Revolution, it's striking.

For those who haven't seen it, it begins with a struggle session, one of these big denunciation rallies in the Cultural Revolution.

And so this story that is all about alien contact in the future is actually pinned around the events of 1966 in a way that I thought actually it was pretty well done in evoking both the specifics of how those sessions looked, but also even the way that people were pressured into denouncing family members and so forth.

And what's striking is that the author, Liu Cixin, says when he wrote the book, he actually wanted those scenes to be at the front in the way that they were in the Netflix documentary.

But when he published it in China, in fact, he had to sort of bury them later in the book because his publisher said, we're never going to get it past the censors otherwise.

So that was sort of interesting that they could be true to his vision.

I think what's more striking about it when you read what he's written about it is that it's not just a plot point, although the Cultural Revolution is not just a plot point in the story, although it does drive the plot, but it seems to me that there is a kind of fundamental cynicism about human nature and about the dangers of humans, which is deeply rooted in his own experiences of the time.

And that's perhaps what's more important about it.

When it comes to why we focus on the Red Guards, I think it's partly because they are visually striking.

There is footage capturing them in full cry.

People see them as being brutal in one sense, but also almost slightly kitsch that they look at them thrusting their little red books in the air.

And it's a sort of-- it's striking.

It's something viscerally people can see.

It's recognizable.

When it comes to things like elite power struggles, they are labyrinthine and hard to follow.

As anybody who's read one of the many brilliant books sort of looking at the political side of the Cultural Revolution like Mao's Last Revolution or Yang Jisheng's book, The World Turned Upside Down, you've got to be paying attention.

It's complicated.

And it seems, I think, to people you can have a much more instinctive grasp of what and who the Red Guards were.

When it comes to things like the factional fighting, again, you talk to people about, well, how come you ended up engaged in physical battles with somebody who two weeks before was your best friend and you were on the same side?

And they will go into these incredibly sort of detailed discussions of kind of abstruse political disagreements.

And it's hard to follow for people.

It's complicated.

It's not visual.

All of these things, I think, have obscured it.

But most of all, of course, is the fact that it's politically inconvenient.

And so certainly, I think for the party, they would much rather people remember a bunch of young people running riot than the leadership's role.

But also, even than the fact that people were having political debates and disagreements and were serious about intensive sort of political discussions, I think that, too, in a way, is slightly threatening.

So I think that's probably why.

First, Tanya, thank you for coming and sharing your insights, and Glenn for hosting.

I wanted to ask a question to actually both of you, since you've both recently been to China.

I wanted to understand if you felt that how Xi is doing things currently, where I feel there's a little bit of the social contract that's existed for maybe the last generation or so, might be fraying, where, hey, the party will give you a good standard of living, and then you just don't question the party.

And then the other part is, has Xi kind of moved beyond the party into a sense of it's now more about him and the consolidation of power as an authoritarian?

And are they setting themselves up for a succession crisis when he steps off the stage?

Or is the party resilient enough, and it will find its way through this?

And so I'm trying to figure out, like these two forces that are at play, that he is really, to me, the instrument behind both.

Is it setting China up for a very unstable situation in the next decade or so when he kind of steps off?

You're the guest.

[LAUGHTER] OK.

I will start.

Briefly, do I think the contract's broken down?

I think for some people it has.

And also because business people, for example, expected that they could basically get on with their lives and have quite a nice standard of living without somebody sort of looking over their shoulder, and they feel like that has changed.

I mean, other people might argue that that would be a good thing, because there was an era of sort of much less restrained, rampant capitalism and soaring inequality.

But there are clearly quite a number of people, and particularly as discussed with the zero COVID policies, I think that sense that the party was at once very repressive and intrusive, but at the same time not very competent.

That was a dangerous moment, I think.

When it comes to Xi's leadership, it feels to me as if there's been these sort of concentric circles of intensified power.

So Xi has undoubtedly intensified his power within the party, but then he's also intensified the party's hold over society.

And he's very much worked through the party throughout his time and through his control of the party structures in a way that's totally sort of counter to that moment where Mao in the Cultural Revolution wants to bring in the masses to overturn those.

I just cannot imagine a point where Xi would do that.

It seems so antithetical to everything we've seen of him so far.

Does that lead to instability in the long run?

I mean, in some ways, I think it causes problems for the party in the shorter run.

For example, who are the people now who will dare to speak the truth to power?

I think anybody would be much more nervous, and you wonder about the quality of information and advice that he will be getting, for example.

All of that said, however, I think you would always be foolish to bet against the party.

It starts with 13 guys in a back room.

It's now still in charge.

It's outlived its big brother in the Soviet Union by a long way.

And it's running the second largest economy in the world.

So it's been extraordinarily flexible and adaptable over time, and it seems to be remarkably resilient.

I completely agree with that.

There was a small event which happened actually earlier this week that speaks volumes, and that is that the People's Daily and a number of China's leading newspapers did not appear on time.

They appeared several hours late in the day, and people were wondering, are they not publishing today for some reason?

And near as anyone can tell, it's because all the people who now hold the power to make the decisions about what the line is to publish today were in Europe with Xi Jinping's delegation, and they're in a different time zone.

So they're answering the emails later in the day.

And so this would not have been true 10, 15 years ago.

I think it's indicative of how the Chinese political system has really changed.

Xi Jinping is also adopting a lot of the accoutrements of a cult of personality that would not have been acceptable previously under several different general secretaries, and that kind of recall metal.

The difference with Xi, as I tried to say earlier, is that he's fundamentally conservative and reactionary.

He fears his people.

He is about repressing his people to maintain party control.

And so that is quite different, I think.

But he's also been very clear over a number of years to be pushing aside all of his predecessors, trying to diminish their role in party history and in the construction of the PRC.

And Mao is the only one who-- he's constructed himself as a peer, if not a better, to Mao.

And what's truly frightening, actually, is perhaps the one piece of unfinished business that Xi Jinping still talks about that Mao could not achieve is the absorption of Taiwan.

So that is worth thinking about.

That would catapult him above Mao.

First, I want to say thank you for speaking today.

I'm the son of two Stanford alums, but I'm also currently an undergrad at UC Berkeley.

Go Bears.

[LAUGHTER] It is right to rebel.

Yeah.

So my question for you is, you mentioned how the state-led suppression of memories and history of the Cultural Revolution led to, in some cases, traumatic psychological effects on people who lived through it.

And could you describe what consequences, if any, has this suppression led to-- or has this suppression had on younger Chinese generations, such as Chinese millennials or Gen Zers who did not live through the Cultural Revolution but are living in a China shaped by it?

One of the things that really struck me was going to view a movie which includes sort of central aspects of this movie had to do with the Cultural Revolution, although obviously it's never really made clear in the film.

And there's certainly no discussion of the causes.

But there's a point where the camera pans around the apartment, and the hero of the film, who's been condemned as a rightist, has had his face cut out of all the family photographs.

And so you see this tracking shot as it goes around all the family photos, and there's just this little scissored empty space.

And all the people in the cinema started laughing.

And I was quite shocked because I actually didn't regard that as a particularly comic moment.

I had met people who had done that.

I talked about the son who denounced his mother.

That family cut his mother out of all the family photographs.

And so the only reason that he had pictures of her now was because friends had kept them, and they were able to go and retrieve them after the Cultural Revolution.

And what suddenly struck me was that all the young people in the audience around me, although they were Chinese, just had no idea that this wasn't some sort of satirical point, but was literally what had happened.

And so there's a large number of people whose knowledge of the Cultural Revolution is very minimal.

And even if they're interested in it, the number of people who said to me something along the lines of, I know something terrible happened to my grandparents, but nobody will tell me what it is.

There's this-- for some people, that means that they don't understand why family relations are as they are or why people behave in certain ways.

For other people, that's given them a sort of a deep fascination that they're sort of trying to fill.

I suppose.

But what to me was more interesting is when you see the unconscious influence spilling over.

So the one that I think was most powerful for me was a young student who had always been brilliantly behaved.

And then while he was at university, he suddenly wrote this very graphic account of how he would murder his tutor and posted this online.

And the university authorities actually seem to have handled it quite sensitively in that they tried to get him help, and he ended up in front of this mental health specialist.

And over the course of various sessions with his family, he discovered to his shock that his father had witnessed his own father, so the boy's grandfather, being murdered by Red Guards.

And he had never breathed a word of this.

But he had brought his son up with this absolute fear of showing anger or strong emotions in any way.

And so to express hatred, anger, any of those things had been completely taboo in this household.

And this man had clearly been trying to protect his child from what had happened in his life, from the trauma he'd endured, not talking about it at all.

And yet somehow these instincts, these sublimated instincts, had played themselves out in the next generation.

And when you talk to psychotherapists, it's clear that these relationships continue without-- perhaps especially when you don't talk about it, these influences continue to impact not just children, but even grandchildren.

It's playing out across the generations.

What I think is hopeful, in a sense, is that younger generations are much more likely to seek mental health care, to recognize that there is an issue.

And as one young psychotherapist said to me, she was working with patients from the Cultural Revolution.

And she said, I didn't know why I was doing this work.

And it was only after I started that I discovered my grandparents had both been victims.

And then I knew why I was doing it.

But she said that for her generation, although there was still an immense trauma there, that they were at least able to stand outside it, to have some kind of distance from it in a way that clearly the people who experienced it in the '60s rarely can.

I wonder if I could seize the microphone for a second and ask you a question, I think, that grows maybe related to that.

Many people who experienced the Cultural Revolution directly later emigrated abroad to societies that had freer environments in which they could digest what had happened to them and perhaps talk to others.

One of the people that you profile on the book is Song Ding Ding.

I wonder if you could, for those who have not read the book, talk about the role that she played in briefly energizing discussion of how to understand the Cultural Revolution, but also the role that Chinese in the diaspora, Chinese abroad, might be playing in advancing or playing a role in the discussion about how to remember the Cultural Revolution that then is injected back into China.

Well, starting at the end point, I think certainly psychotherapists, for example, have said to me they've had patients who said, it's only now I'm outside China that I can talk about this, even in the privacy of a therapy room that I never felt able to discuss this before.

So certainly there are people who are more able to address those events and more willing to.

And of course, as well, because the atmosphere has grown increasingly repressive, there are more and more scholars, particularly scholars of the era, who have been forced to move away, but often to US benefit in particular, but elsewhere in the West as well.

And so there's now a level of knowledge outside because they can't talk about these things at home.

So that's definitely something that's shifted.

I should also say, even when living abroad, some people still feel they can't talk about it.

One of the figures in the book is someone who has tried to document those who died in the early stages of the Cultural Revolution.

And she talked to me about ringing up.

She's living in the US.

She talked to me about ringing people up in the US.

And they were still saying, you've got to get off the phone, somebody will be listening to us, even on a US to US call.

So there is still a level of profound fear there for many of those who's left.

And then, sorry, the first part wasn't Songbinbin.

This is a very complicated case, which will try to boil down.

In the very early days of the movement, she and a school friend put up what were known as big character posters criticizing their principal.

And matters escalated from there.

And ultimately, that principal, vice principal, Bien Jong-Yun, was murdered by other teenage girls at the school.

It has to be said that there is no evidence that Songbinbin was involved in her death directly.

But rumors spread, and her name quickly became tarred with all of this.

And she also was the young woman who, at one of Mao's great rallies on Tiananmen Square of all the Red Guards, climbed the podium and put a Red armband, a Red Guard armband on him.

And was lauded all over the newspapers of the time as the face of the revolution.

He famously said to her, what's your name?

And when he heard it, said, oh, Binbin, as in gentle or refined.

And she said, yes.

And he said, oh, well, yeah, be martial, basically.

Be violent.

So that was the name that she was then given in the newspapers.

And the image was of a zealous Red Guard at the forefront of this very passionate, violent movement.

And he really became emblematic, I suppose, of the violence and the turmoil of that time.

What then happened was that in 2012, she issued an apology to her teacher and to the family of her teacher.

And she'd been encouraged to do this in part by a Chinese historian who hoped that it was going to spark a greater understanding of the era and a willingness to address it.

But in fact, what happened was that it sparked incredible rancor and division and debate because many people said, well, this just isn't a good enough apology, or it's not sincere enough, or she's not honest enough about her role.

OK, maybe she didn't beat her teacher, but she should have done more to stop it.

And this is just an attempt to clear her name and unburden herself and so forth.

And so actually, what could have been this moment of reconciliation instead somehow seemed to inflame the subject.

Certainly, the teacher's widower was extremely angry and felt it was insincere.

And it really seemed to shut down what had looked like a possibility that people would be able to turn back and talk about the Cultural Revolution more honestly, more openly.

And instead, it seemed to have quite the opposite effect in a way.

And I think it does point to the fact that while the primary reason for suppression of discussion has been the authorities' determination to maintain political control, I think they probably are concerned as well by social cohesion.

And particularly because people haven't been able to talk about this honestly and openly for decades, you can't just take the lid off it and expect everybody to have a kind of calm and reasoned conversation.

Perhaps that was never going to happen anyway, but it's certainly not going to happen when the subject's been shut down so comprehensively for so long.

Thank you so much for this excellent talk.

And I wonder if I'm actually asking a question that's still the flip side of Colleen's previous question.

And one thing that my students keep wanting to talk to me about when I teach my Cultural Revolution in my Chinese politics course here is that they are seeing increasingly in the past couple of years in the context of US-China relations the phrase Cultural Revolution popping up in American social critique, commentaries, public essays.

There is a book by Christopher Rufor called The American Cultural Revolution, and it is increasingly used as a phrase to refer to the general sense of radicalism perceived to be shared by students, et cetera, the critiques of students and teachers and institutions, et cetera.

And I wonder if you have thoughts on this phenomenon.

I wonder if you think, for example, the diasporic community that we just discussed, whether you think they played a role in consolidating some sort of interpretation of the Cultural Revolution outside China.

Thank you so much.

Yeah, I mean, for me, it's such a fundamental misconception of what the Cultural Revolution was, that it's seen as young people getting carried away and being crazy and unrestrainable and vicious, as opposed to being a movement initiated by a political leader.

And yet, as you say, it seems to be so potent and so powerful and to keep perpetuating itself as a sort of a criticism so that any form of student protest becomes tarred with this.

And obviously, I think part of that is about delegitimizing student protest movements, student challenges.

I mean, there is also the fact that it sometimes seems in a discussion, it becomes such a free-for-all how you use the phrase.

So for example, in the discussion on Song Bin Bin, some people were saying that criticizing her showed a Cultural Revolution mindset, for example.

And other people were saying, well, defending her is a Cultural Revolution mindset.

So it's almost sort of become detached from meaning and become more of a slur than anything else.

I think for people who lived through it, their fear of what happened and of revival can be so potent that sometimes it's invoked in circumstances where it doesn't make a great deal of sense to me.

But perhaps for some people in the diaspora, it is an instinctive reaction.

In the same way that, for example, I spoke to somebody who'd been very involved in the events in Chongqing and the factional fighting, and he told me about trying to prevent his son from becoming involved in the 1989 protests in Tiananmen.

Because for him, large numbers of young people massing together in Tiananmen Square was just a fundamentally viscerally threatening thing.

And so the fact that the whole mood of it and the intent of it and the origins of it were different, to him, he just couldn't get past seeing a lot of young people being politically active.

That was just in itself too redolent of the era.

Tanya, thanks for this.

It's an amazing book, but it's also an excruciating read.

And I wanted to ask you to talk a little bit more about something you said a minute ago, about the difference between reliving and remembering.

I've been fortunate enough to be on the receiving end of some very emotionally deft interviews with you.

And I'm curious to know about some of the people that you talked to and how you navigated the moments when remembering was reliving and was incredibly traumatic for people.

If there were interviews that you felt you couldn't complete with people or people who couldn't complete the conversations with you, this is very difficult stuff to write about.

And I'd just be interested to hear a little bit more about how you actually managed some of those issues.

Thanks.

I think for me, because it was a self-selecting group of interviewees in the sense that what interested me was the fact that they had chosen to keep the memory of this era alive.

And I wanted to be very much led by them.

And so particularly in the first interviews I did, because in most cases I went back to people several times, I wanted them to tell me the story in the way that they wanted to tell it.

Because that was an important part for me of understanding what it meant to them and how they understood it.

But then yes, obviously there are times when you're asking difficult questions and you're thinking about how much space to give people.

And do you ask them now or do you maybe just give them that breathing space and return to it next time?

This is a question for both of you.

And it's more of a broader observation as opposed to only your book.

I kind of think at times about the power of incumbency, where somebody is in power in any country, either now or in the past.

And despite them being dictator or vicious rulers, they rule for decades and decades.

And then they continue to perpetuate either by bringing in their family like North Korea, or I look at the folks in Latin America, in India, moguls, 600 years.

And I look at even Britishers, 200 years.

And they did it on a more official basis.

But tremendous amount of stuff occurs and people put up with it.

So what I see is that in society, we seem to accept incredible amount of misery and we adapt to it as opposed to changing such as cultural revolution and the others.

And that certainly has happened in China.

On the other hand, I see that democracy, which of course I'm very fond of, I see that's where the instability comes in.

And people do try to have a family dynasty, whether it's Clintons or Bush or Kennedys and the like.

And that continues to happen.

But by and large, much better way of going about it.

Whereas when I see China, as much as I kind of wonder about all the points you made about Xi, he has made China from $600 GDP to now $6,000, $7,000, and has done an amazing job.

Whether it's stealing of the IP, getting right people to do something, but increase the lot of China so that one or two generation may suffer a lot, but the rest of the next generation or two generation after has done-- will do hopefully far better.

What's your view on how does this transition occur?

What is the role of this cultural revolution or evolution versus the increase in the society's standard of living down the road?

I mean, I think the Cultural Revolution was one of the chief reasons that China abandoned the course it was on and turned towards the free market.

And a lot of it, frankly, was about liberating people.

I always slightly shy away from this idea that the Communist Party has lifted the Chinese people out of poverty because I think people lifted themselves through sweat and tears and literally blood in many cases, that people have had to achieve this.

But also, politically, as I said, the turn towards the market came really because the Cultural Revolution was such a disaster.

It was clear lots of things weren't working anyway.

And obviously, the Great Leap Forward really exacerbated the sense that there was something fundamentally wrong in the party's direction.

But I don't think China could have transformed at the speed it did and in the way it did without the break of the rift caused by the Cultural Revolution.

There are some people who argue that the foundations laid in rural industry in the Cultural Revolution actually helped China's economy to develop later.

There's also-- certainly, it's true that when you look at the small-scale entrepreneurs who are allowed in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, that was partly a pragmatic decision because they had all the people, the educated youth who'd been sent down to the countryside, they had them coming back to the cities without much of an education, going up against a pool of younger people.

They didn't have jobs for them.

And so it was quite pragmatic to encourage small-scale entrepreneurship as well.

From that point of view.

And then as I said earlier, I do think that that experience of scrabbling and surviving and having to be quite individualistic to make your way in the Cultural Revolution actually was one of the things that contributed to that much more individualistic mindset in the capitalist era.

The story I always think of is of the guy who was known as the blank paper hero because when the colleges reopened in the Cultural Revolution, you had to do exams to get into them.

But it was basically all about your political skills.

He sat the exam paper, could only answer two questions, and he turned over the paper and wrote on the back basically a screed about how he would have done brilliantly except that he devoted himself to the party's causes and to laboring in the fields and being a good communist, unlike all these selfish bookworms who'd been studying.

And he ended up being allowed into college on the basis of this political statement, so-called.

So he went off to farming college, rose up through the ranks, and he ended up selling his animal feed company or selling his shares in an animal feed company for around, I think, something like $18 million a few years ago.

And I thought, if you wanted a more perfect transition of how learning to maneuver in those treacherous waters of the Cultural Revolution and grab any opportunity that you could, prepared yourself to the move to the free market, that was probably it.

I think there's a real sense in which the Cultural Revolution helps to explain the headlong rush into the future that China since the late 1970s and through the present has experienced.

They do not look back.

It's too painful.

It's too divisive.

Focus on forward.

And society, I think, Chinese society, the party, was wise enough to enable it, to tap into its energies and its talents and to allow them to lift themselves out of poverty and build the China that we see today.

But I think in a very real sense, Xi Jinping is turning back the clock on the conventions that were arrived at after the Cultural Revolution.

From the origins of the party, there's been a big debate about the relationship between the party and day-to-day governance.

And after 1949, it was formulated as the relationship between party and state.

One of the conventions that arose after the Cultural Revolution briefly was that the party should back off somewhat from day-to-day governance.

Xi Jinping, particularly after 2018, has reinjected the party back into granular state governance in a way that it was not present really before and has kind of broken through that taboo in a way, partly, I think, to aggrandize his own power.

And so the danger really is that rather than Xi Jinping sort of catapulting China forward, in fact, he's actually regressing and then squeezing the society, the life out of the society in a way that will hold China back and hold the Chinese people back.

And I think that's the most tragic thing about this particular moment.

After the death of Mao Zedong, I believe the Gang of Four was imprisoned.

But my question is, was there any judicial consequences for other leaders, some of the Red Guards, people who committed some of the most egregious crimes?

And along the same lines, is there a feeling among many people in China that justice was never done, about the cultural revolution?

So certainly, there were massive shortcomings in the legal process, to put it mildly.

Many people-- there's a huge number of murders that were never pursued.

As I said, part of that, I think, was that in many cases, people had quite good connections, and it was too embarrassing to pursue those involved.

But very definitely as well, it was about prosecuting people who'd been on the left, essentially.

So the Gang of Four, but also people lower down the system who were associated with the Gang of Four all ended up in prison, even at regional levels.

Having said that, and while the trials of the Gang of Four were clearly show trials, nonetheless, they were given lawyers, even if in Zhang Qing's case, she didn't choose to use them.

They couldn't plead not guilty, but there was a legal process.

And it sounds very odd, but that did matter after just the chaos of the Cultural Revolution years, in the sense that anybody could turn on you.

There was a legal process.