The Russia and Eurasia Collection is one of the world's great scholarly resources for the study of this area in the twentieth century and contains some of the most important holdings of the Hoover Institution. Geographically it includes Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, the Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. Subject areas include twentieth-century history, politics, government, economics, military affairs, and political and social movements, especially the Russian Revolution and communism.

The collection endeavors to gather and preserve documentation within its subject and geographic areas, including monographs, periodicals, newspapers, pamphlets, government documents, ephemera, manuscript collections (such as personal papers and organizational records), films, posters, photographs, and maps. The majority of the collected materials are in Russian; however, materials can be found in all the languages of the CIS states, as well as in most Western languages.

Collecting Russian and related materials began in 1919, when, at Herbert Hoover's instigation, Professor E. D. Adams from the history department at Stanford University went to Paris to gather documentation on the First World War and the ensuing peace conference.

The first materials on Russia came from members of the Russian political conference, in which two prominent politicians and diplomats, Vasilii Maklakov and Sergei Sazonov, played leading roles.

In September 1920, Professor Frank Golder, a specialist on Russian history who had lived in Russia before and during World War I, was sent to Eastern Europe as a roving acquisitions agent for the Hoover Library. He and Professor Harold Fisher of the American Relief Administration acquired quantities of material: books, pamphlets, periodicals, newspapers, and archival collections dealing with Russia and its former provinces of Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Ukraine.

An additional trip by Golder to the then independent Caucasian states produced further documentation.

Golder obtained the greatest amount of published matter concerning Russia when he participated in the American Relief Administration mission to Soviet Russia between 1921 and mid-1923.

With funds provided by Herbert Hoover, Golder acquired more than 40,000 valuable items, aided by Anatolii Lunacharskii, who was the Soviet People's Commissar for Education. Along with the previously gathered documentation, these acquisitions from Russia served as a solid foundation for further developing the Hoover Library collection.

The appointment of area specialists as curators for particular area collections guaranteed a high level of scholarly attention to the selection and organization of the materials. In 1924 Dimitry M. Krassovsky, a Russian-trained lawyer and a graduate in library science from the University of California at Berkeley, became the first curator of the collection. Former General N. N. Golovine became the acquisitions agent in Europe. Both men, particularly Krassovsky (1924–47), contributed substantially to the growth and quality of the collection. Succeeding curators and their dates in office include Witold Sworakowski (1947–64), Karol Maichel (1964–74), Wayne Vucinich (1974–77), Robert Conquest (1981–2001), Joseph Dwyer (2002–07), and Anatol Shmelev (associate curator 2006–10, curator 2011–Present ).

For more than eight decades, the collection on Russia and related areas has been systematically expanded. Gaps that emerged during World War II and in the late Stalin period, when acquisitions from the Soviet Union were limited, have been filled in with original materials or microfilms. Since Witold Sworakowski wrote the first survey of Hoover's Russian and Eurasian Collection in 1954, the collection has grown more than tenfold.

The fall of communism and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 have brought about another great period of growth for the Russian/CIS Collection.

Twelve Years of Cooperation With the Russian Archives (PDF) discusses Hoover's various microfilm, oral history, and publishing initiatives involving Russian archives since the 1990s.

The Russia and Eurasia Collection emphasizes the twentieth century, though some materials from the latter half of the nineteenth century are also included. In accordance with the Hoover Institution's dedication to the study of war, revolution, and peace, the collection is concerned primarily with the history, ideology, politics, and international relations of Russia and the former Soviet Union. There are also holdings related to economics, demography, and law. This collection is one of the most outstanding features of the Hoover Institution. Few libraries in the world can match its depth or quality. It encompasses writings on Imperial Russia after 1861, the period of the Provisional Government of 1917, the Bolshevik revolution, the Civil War, the Soviet period, and contemporary events.

The various national collections of library materials for the area of Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States, with approximate volumes of holdings, are as follows:

|

Collection |

Monographs |

Periodicals |

Newspapers |

|

Belarus |

5,000 |

70 |

35 |

|

Central Asia/Transcaucasia |

12,000 |

30 |

25 |

|

Russia |

310,000 |

6,000 |

1,200 |

|

Ukraine |

13,000 |

300 |

140 |

|

TOTAL |

340,000 |

6,400 |

1,400 |

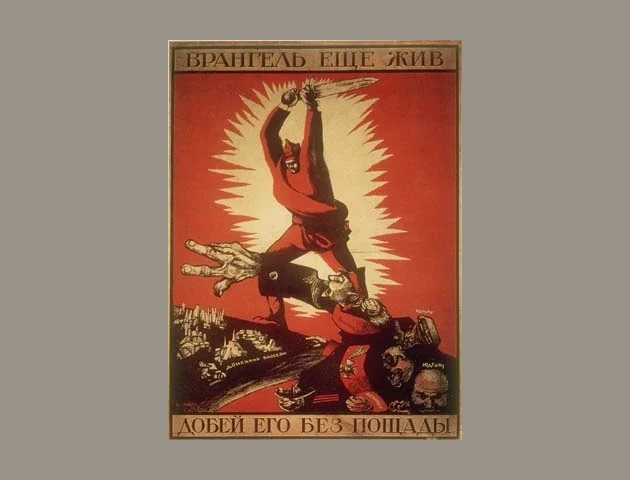

In addition to monographs and serials, the collection encompasses 26,000 reels of microfilm, 750 motion pictures, more than 1,000 manuscript collections, 20,000 pamphlets, 10,000 political posters, and 23,000 photographs.

Files of more than 1,400 newspapers are held, ranging from imperial Russian newspapers of the late nineteenth century to many hundreds of files from the Soviet period, including complete files of such important newspapers as Pravda and Izvestiia. For the post-Soviet period, the Russian/CIS independent opposition press collection of some 3,000 titles (20,000 individual issues) is a unique resource.

The Russian/Soviet pamphlet collection of more than 20,000 pieces consists of ephemeral materials seldom collected or preserved by other repositories. The pamphlets cover all aspects of Russian and Soviet history of the twentieth century.

Hoover also possesses a massive collection of Russian and other Soviet government documents (some 5,000 volumes). Included are Imperial Russian government documents; a complete collection of laws of the Russian empire; Duma records, ministry records, and documents of local gubernias and cities; and a comprehensive collection of government and Communist Party documents for the Soviet period.

The library also has a collection of Russian art books. Many of these were collected by the first Russian curator, Frank Golder, in the years following the 1917 Revolution. Among them are such valuable and beautiful volumes as Alexandre Benois's Tsarskoe selo (St. Petersburg, 1910); Al'bom 200-lietniago iubileia imperatora Petra Velikago 1672-1872 (St. Petersburg, 1872); I. N. Bozherianov's Nevskii prospekt (St. Petersburg, 1901); V. Durasov's Rodoslovnaia kniga vserossiiskago dvorianstva (St. Petersburg, 1906); Obshchii Gerbovnik Dvorianskikh Rodov vserossiiskiia imperii nachatii v 1797-m godu (St. Petersburg, 1798); Russkiia narodniia kartinki sobral i opisal D. Rovinskii (St. Petersburg, 1881); and Istolkovaniia aglinskikh zakonov G. Blakstona, perevedenniia po vsevisochaishemu povelieniiu Velikoi zakonodatel'nitsi vserossiiskoi s podlinnika aglinskago (1780).

Within Hoover's extensive collections on twentieth-century Russia and other former Soviet republics, certain areas are particularly well documented. The late prerevolutionary Russian empire (ca. 1870–1917) is represented by a large collection of publications, many rare and even unique in the United States. There are especially strong holdings on:

- The rise of political parties

- Imperial Russian diplomatic archives

- The revolutionary movement

- Asiatic Russia and its colonization

- The Okhrana (tsarist secret police)

- The Russo-Japanese War

- Russia's participation in World War I

Nearly complete documentation is available in the library on Russian legislation, the dumas, and the first general census of 1897. Files of prerevolutionary periodicals and newspapers are abundant.

In addition, Russian and Soviet materials are among the most significant of the Hoover Institution's archival holdings, making up approximately 1,000 individual collections. They document the tsarist regime between 1880 and 1917 (especially diplomacy), revolution and counterrevolution, war relief, civil war, emigre' movements, and the USSR. The Hoover collection on the 1917 revolutions, the provisional government, and the civil war is probably the best collection in the West. Documentation on the provisional government, including official gazettes, legislation, and ministerial publications, is extensive, as is research material on the civil war, including activities in Ukraine, Byelorussia, Siberia, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Mongolia.

The largest part of the library collection deals with the Soviet period. Subject areas particularly well covered are:

- War communism, 1918–1921

- Terror and forced labor

- Antireligious action

- Separatist movements and the nationality question (including the "Ukrainian Tsentral'na Rada," the Ukrainian National Republic, the Western Ukrainian Republic, the Transcaucasian Republics, and the Basmachi in Central Asia)

- The New Economic Policy (NEP) period, 1921–1927

- The peasant question and collectivization (especially in Ukraine and Kazakhstan)

- Economic planning

- Soviet foreign policy

- The Comintern

- Trade unions

- The Soviet military

- The Russo-Finnish War, 1939–1940

- The Soviet Union in World War II

Outstanding coverage is found for:

- The Soviet Communist Party (including minutes of partycongresses, plenums, secretariat documents, etc.)

- Dissident and opposition movements (including samizdat materials)

For the postcommunist period, strengths are found in:

- The "opposition" political press

- Postcommunist political parties

- Postcommunist elections

- Ethnic policy and ethnic conflict (in Russia and other former Soviet republics)

The Institution's archives possesses more than 250 individual archives on Imperial Russia and the Provisional Government period, constituting the most significant accumulation of documentation on pre-1917 Russia anywhere outside that country. The Nicolas de Basily Room—centerpiece of the collection—is the result of the generosity of Mrs. Lascelle de Basily, who created this memorial to her husband, Nicolas de Basily, a Russian diplomat and statesman who left Russia after the revolution of 1917. The room contains his extraordinary collection of portraits of Russian emperors, courtiers, diplomats, and statesmen; landscape paintings; miniatures; and other works of art. Most remarkable are the portraits of reigning sovereigns: Empress Elizabeth, Empress Catherine II (Catherine the Great), her husband, Peter III, their son Emperor Paul I, and Paul's son Emperor Alexander I.

Original manuscript materials on the Imperial Russian family are especially noteworthy. There are fifteen manuscript boxes of letters written by Mariia Feodorovna (empress-consort of Alexander III, emperor of Russia) to Alexandra (queen-consort of Edward VII, king of Great Britain), letters of Georgii Mikhailovich (grand duke of Russia), and letters of Kseniia Aleksandrovna (grand duchess of Russia and sister of Nicholas II, emperor of Russia). Other nobility represented in the collection include Princess Barbara Dolgorouky, Baroness Maria F. Meiendorf, the Cherkasskii family, and the Obolenskii family.

Diplomatic and political papers on pre-1917 Russia are extensive. They include, among others, records of the Russian embassies in Paris (1917–1924) and Washington, D.C. (1900–1933); records of the Russian consulates and legations in various German cities (1828–1914); the Paris files of the Imperial Russian secret police (Okhrana); and papers of numerous Imperial Russian and Provisional Government officials, such as Nicolas Alexandrovich de Basily (deputy director of the Chancellery of Foreign Affairs, 1917), Sergei Dmitrievich Sazonov (minister of foreign affairs, 1910–1916), Vasilii Alekseevich Maklakov (ambassador of the Provisional Government to France, 1917–1924), Dimitrii Nikolaevich Liubimov (chief of staff of the Ministry of Interior, 1902–1906), Mikhail Vasil'evich Alekseev (chief of staff of the Russian Imperial Army), and Dimitrii Grigorevich Shcherbachev (general, Russian Imperial Army).

The tsarist secret police, known as the Okhrana, maintained an office at the Imperial Russian embassy in Paris to monitor the activities of revolutionaries who were trying to topple the tsar. The files of this organization are a unique source on the internal operations of the revolution. Covering the period 1883 to 1917, they include transcripts of intercepted letters from suspected revolutionaries, police photographs, code books, more than 40,000 reports from 450 agents and informers operating in twelve countries, and dossiers on all the major revolutionary figures.

Another extremely valuable collection on revolutionary Russia consists of rare materials assembled by Boris I. Nicolaevsky, a prominent Menshevik during the Russian Revolution. Following the revolution, he emigrated to Paris and was later described by Lenin's biographer Louis Fischer as "undoubtedly the greatest expert in the Western world on Soviet politics and Marx." His collection contains rich documentation about the party and prerevolutionary Russia, including letters and papers from Trotsky, Lenin, Bakunin, Herzen, Lavrov, Plekhanov, Akselrod, Martov, Tseretelli, and Chernov. In the Trotsky file are approximately three hundred letters exchanged between Leon Trotsky and Leon Sedov, Trotsky's son and closest political collaborator. The letters, which were recently added to the collection following the death of Nicolaevsky's widow, cover the period 1931–38 and reflect Trotsky's thoughts and recollections during a crucial period of political upheaval in the Soviet Union, when Stalin purged the communist system of Trotsky's influence.

The Herman Axelbank film collection on Russia (1890–1970) contains more than 250,000 feet of film documenting activities of the tsar, his family, and his associates; the two Russian revolutions of 1917 and their leaders; the Provisional and Soviet Governments; Soviet military forces in World War II; and Russian culture and economy. It includes film of the March 1921 Kronstadt mutiny, the first purge trials of Social Revolutionaries in June 1922, and many political figures of the time (Kerensky, Lenin, Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Stalin). According to one film expert, it is "undoubtedly the largest and most valuable film collection devoted to the subject of revolutionary and prerevolutionary Russia in the Western hemisphere, and probably in the Western world."

The Russian Civil War period is well represented by the papers of Mikhail Nikolaevich Girs (chief diplomatic representative of the Vrangel' government), Petr Nikolaevich Vrangel' (commander of the White Russian Volunteer Army, 1920), Nikolay Nikolayevich Yudenich (commander of the White Russian Northwest Expedition, 1918–20), Boris Vladimirovich Gerua (chief of the White Russian Military Mission to London), and Evgenii Karlovich Miller (chief military representative of General Vrangel' in Paris).

Apart from the unique tsarist secret police files and the Axelbank film collection, the archives holds extensive documentation on the communist seizure of power in the countries of East Central Europe and the Baltic states after World War II. These materials include some 43,000 certificates issued to prisoners released from forced labor camps in the Gulag Archipelago.

At the present time the Institution continues to build the collection on Russia, the Soviet Union, and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Of special interest are several recent acquisitions.

The first is the Archives of the Soviet Communist Party and the Soviet State, which relates to political conditions in the Soviet Union from 1917 to 1992. Microfilmed from 1993 to 2004, from finding aids and holdings dating from 1903 to 1992 of the Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv sotsial'no-politicheskoi istorii (RGASPI, Russian State Archives of Socio-Political History), the Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv noveishei istorii (RGANI, Russian State Archives of Contemporary History), and the Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii (GARF, Russian State Archives of the Russian Federation), this project produced more than 11,000 reels of microfilm.

The second is the Hoover/Gorbachev collection of oral histories. This consists of audiotaped interviews of political figures of the former Soviet Union (such as Bolsheviks and former members of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party) and prominent players in today's Russia (for example personages from the perestroika period and leaders of current political parties and movements). More than one hundred such interviews have been completed.

The third area is the Russian/Soviet Opposition Press Collection. From 1987 to the present, the Russia/CIS Collection has been amassing the political opposition press from Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and other parts of the former Soviet Union. From 1987 to 1991, the opposition consisted of the "democrats"; since 1991 it has consisted of Communists and others on the left as well as the national patriotic groups and fascists on the right. Today the political opposition press collection is composed of nearly 3,000 serial titles (some 20,000 individual issues) and is probably the largest such collection in North America, filling approximately 500 manuscript boxes. Bibliographic data on the holdings is available at Hoover.

For several years Hoover has been building an archival collection of political party documents from postcommunist Russia and other former Soviet republics. More than one hundred political parties and social action groups are represented in the collection by such materials as programs, platforms, by-laws, constitutions, minutes of meetings and congresses, leaflets, and posters. The most outstanding part of this collection is a copy of the archives of the Democratic Russia Movement, an umbrella political organization of Russian democratic parties and groups. The Democratic Russia Movement was a moving force behind Boris N. Yeltsin's campaign for the Russian presidency in 1991. Since 1989 Hoover has made a major effort to collect all possible materials (official publications, pamphlets, brochures, photos, leaflets, posters, candidates' ephemera, buttons, and artifacts) dealing with national elections in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, as well as selected local elections, such as Crimea, Vologda Oblast, Komi Republic, and Altai Krai. Hoover is a prime source for anyone wishing to study such elections.

Finally, Hoover is collecting documentary materials on the so-called hot spots in the former Soviet Union: Transdnestria, Crimea, Abkhazia, Southern Ossetia, Chechnia, and Karabakh. For example, for Transdnestria there are materials from Igor Mikhailov, the former representative of Transdnestria to Moscow; for Abkhazia, materials from Taras Shamba, president of the World Congress of Abkhaz and Abaza Peoples; and for Karabakh, the Vahan Emin collection on Armenians in Azerbaijan.