In October 2015, Dreamworks Pictures will release Bridge of Spies, a cinematic thriller based on the life of James B. Donovan, a lawyer-turned-hostage negotiator whose archive is housed at the Hoover Library & Archives. Directed by Steven Spielberg, written by Matt Charman and Joel and Ethan Coen, and starring Tom Hanks, the film tells the story of a Brooklyn-based lawyer who, during the height of the Cold War, undertook the unpopular job of defending suspected Russian spy Rudolf Abel—and then, after Abel was convicted, negotiated the KGB agent’s exchange for an American U2 pilot captured by the USSR.

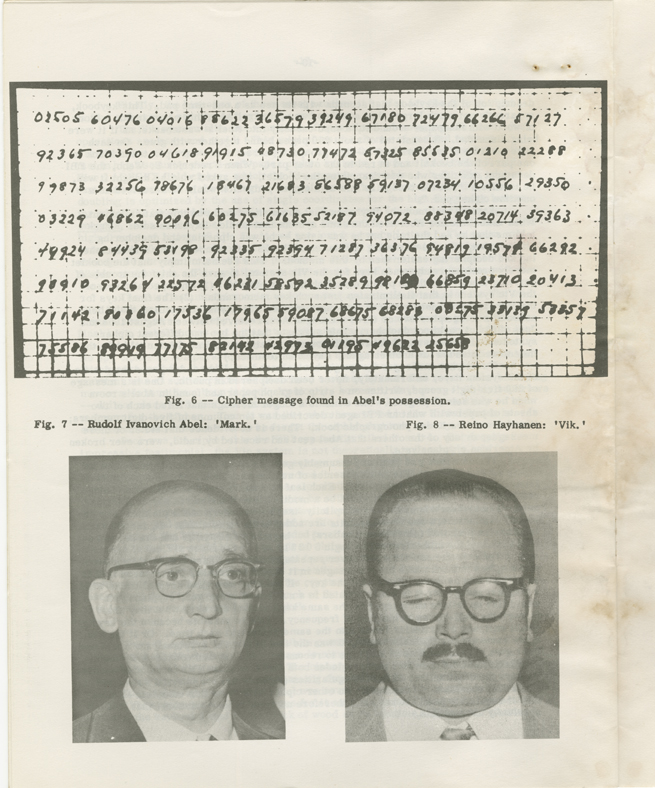

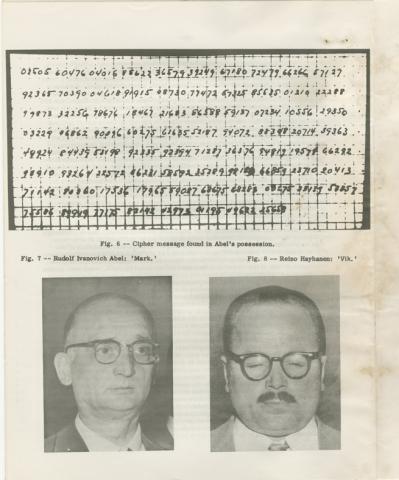

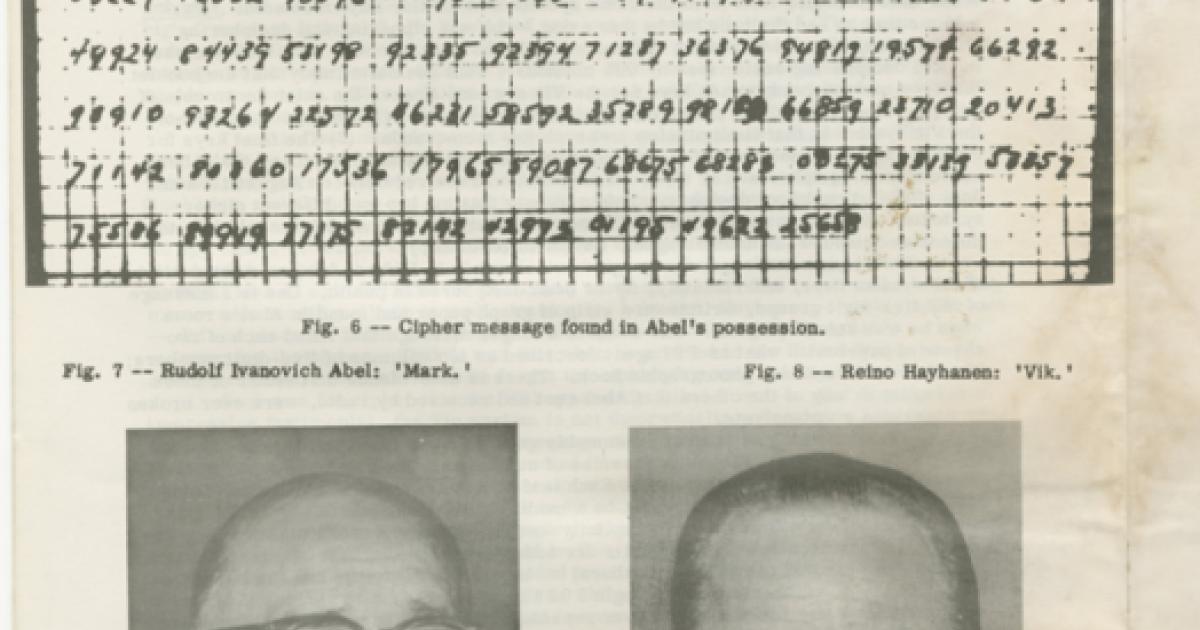

The dramatic story of Donovan’s Cold War exploits is documented in the photographs, diaries, memoirs, notebooks, and correspondence contained in the extensive James B. Donovan Papers at the Hoover Library & Archives. From ciphers used in the famed Hollow Nickel Affair to rubles given Donovan by KGB operatives, the collection provides vivid insights into one of the most publicized lawsuits and spy exchanges of the twentieth century.

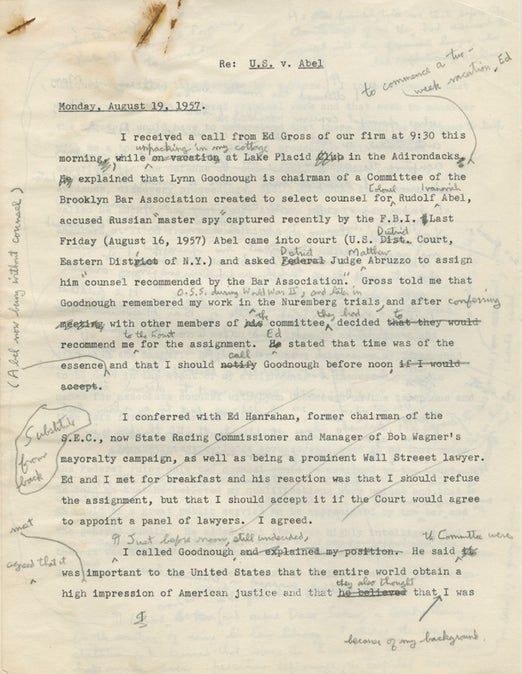

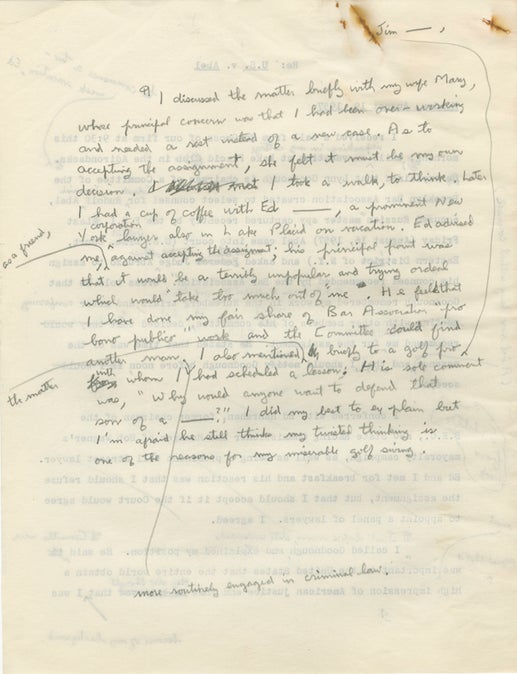

Born in 1916 in New York City, Donovan attended Fordham University and later attained a law degree from Harvard; during World War II, he served as general counsel of the Office of Strategic Services and in 1945 as assistant to the US chief prosecutor of the International Military Tribunal at the Nuremberg Trials. Thus, by the time Rudolf Abel was arrested by the FBI on charges of conspiracy in 1957, Donovan was a well-regarded attorney with extensive military experience—making him a prime candidate to defend the alleged spy. Before approaching Donovan, the Brooklyn Bar Association had courted many young, ambitious lawyers, but each had turned down the case, fearing the bad publicity of aligning their names with such a high-profile, unpopular defendant. In a draft of a memoir of the case in the Donovan archive, Donovan offers an amusing anecdote related to discussing the possibility of taking the case with his golf instructor, who asks, “Why would anyone want to defend that son of a ___?” Donovan notes that he did his best to explain legal due process, but the golf pro still found his student’s “twisted thinking” as a reason for his “miserable golf swing.”

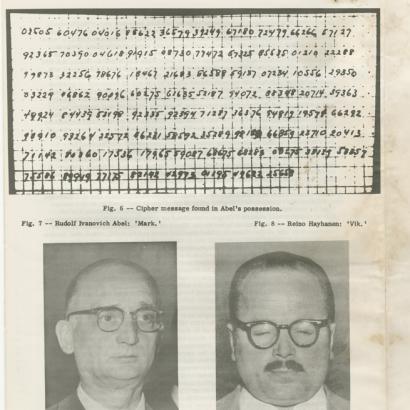

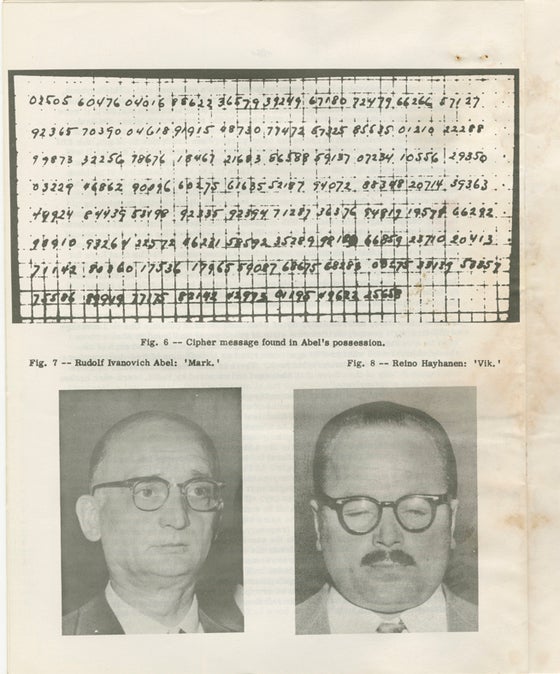

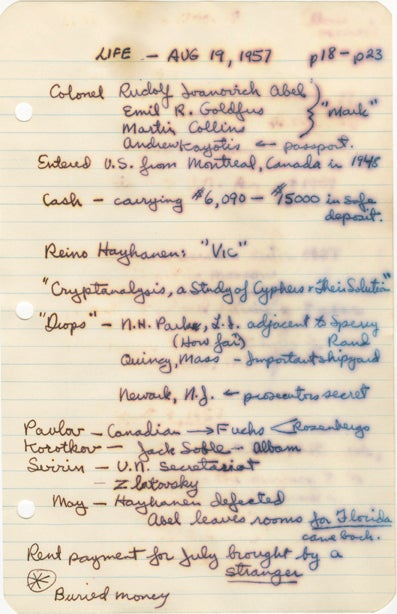

Implored by legal colleagues, however—and intrigued by the espionage ring unearthed by Abel’s arrest—Donovan finally agreed to take the case. Due to overwhelming evidence against Abel—including decoded messages, false identification papers, and damning correspondence found during a search of the defendant’s apartment—Donovan lost the suit, and Abel was sentenced to forty-five years in prison. Subsequent to the trial, Chief Justice of the United States Earl Warren praised Donovan for taking Abel’s case after so many attorneys had refused. The Donovan archive at Hoover, which includes Donovan’s notes and research materials for the trial, documents how extensive and convincing the evidence against Abel was. As seen in the image on the right, the collection houses the extensive notes kept by Donovan’s assistant Thomas Debevoise (later the attorney general of Vermont), who made exhaustive lists of Abel’s aliases, code names, dead drop sites, associates (including Julius and Ethel Rosenberg), and items confiscated from hotel rooms and apartments where Abel had stayed. Among the items mentioned are “buried money” and a variety of radio and wiretapping apparatuses (Abel had worked as a telecommunications operator for the KGB subsequent to World War II).

A manuscript of a memoir entitled “Defense of a Spy,” written by Donovan perhaps as an early draft of his later book, Strangers on a Bridge (1964), documents the evidence the FBI had gathered against Abel, as well as Donovan’s conversations with his client regarding the US government’s accusations of conspiracy and espionage. Bridge of Spies film stills recently released by Dreamworks Pictures feature images of Donovan, played by Tom Hanks, questioning Abel, played by Mark Rylance, in scenes reminiscent of those found in manuscripts from the Donovan archive. In his first conversation with Abel, Donovan emphasized that the government would seek the death penalty unless Abel agreed to work in counterintelligence or could prove to be of legitimate Russian military rank and thus deserving the status of political prisoner. In this conversation, Abel admitted his guilt, refused to cooperate with the American government, and described his rank as “quasi-military”:

“He [Abel] asked me what I thought about his situation, adding with a smile that he was afraid he had been ‘caught with his pants down.’ I agreed with him and said I frankly thought that with the new penalty of capital punishment for espionage it would be a miracle if I could save his life. I told him that just from the press reports, and a quick glance at the official file in the Clerk’s office, the evidence of the facts appeared to be overwhelming; that it would only be through some possible legal defect in the process of the trial, plus a tremendous change in public opinion, that his life could be saved. I stated on the latter point that it would be important to see the public effect of my first press conference, of which he seemed to have learned. He made a few gloomy observations on obtaining a fair trial in an atmosphere ‘still poisoned by McCarthyism.’”

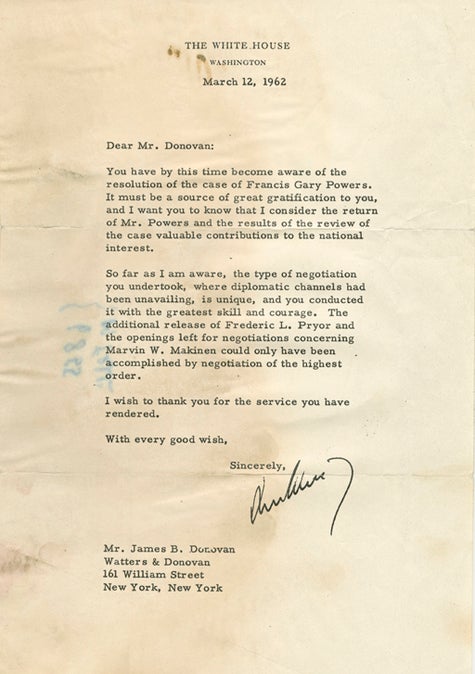

for Donovan's help in negotiating the Abel-Powers

exchange on the famed Bridge of Spies (James B.

Donovan Collection, Envelope E)

Despite the overwhelming evidence against his client, Donovan performed the miracle of saving Abel’s life—largely by arguing that Abel had been a “Colonel” in the Soviet intelligence service. Unlike the Rosenbergs, US citizens and traitors against their country, Abel and his espionage activities had been sanctioned by a state power and therefore did not fall under the rubric of demanding the death penalty.

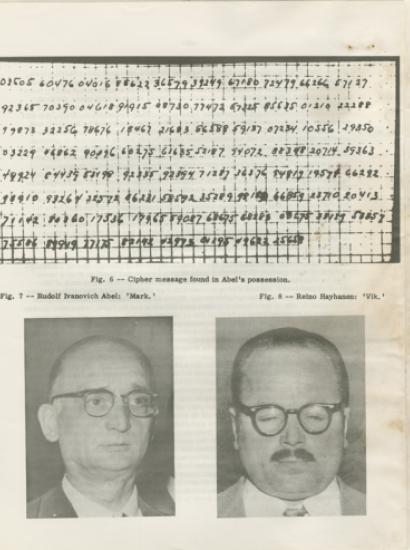

Jim Donovan’s involvement with Rudolf Abel would not end in 1957, when Abel was convicted and incarcerated in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. In 1960, after an American U2 spy plane was shot down over the USSR and its pilot, Francis Gary Powers, was imprisoned and interrogated, the CIA approached Donovan to appeal for help in negotiating an exchange of Abel for Powers. As documented in his archive, Donovan spent several often-exasperating months negotiating with the KGB agents in charge of the custody of the fallen American pilot before coming to a trade agreement. To enable the exchange, then attorney general Robert Kennedy commuted Abel’s sentence. On February 10, 1962, after months of negotiations, Powers and Abel crossed the famed Bridge of Spies—the Glienicke Brücke, a small steel structure that crosses the Havel River and links Berlin with Potsdam. Beginning with Abel and Powers, the Glienicke Brücke would become the site of several high-value spy exchanges between the USSR and the West, thus becoming a lasting emblem of the Cold War.