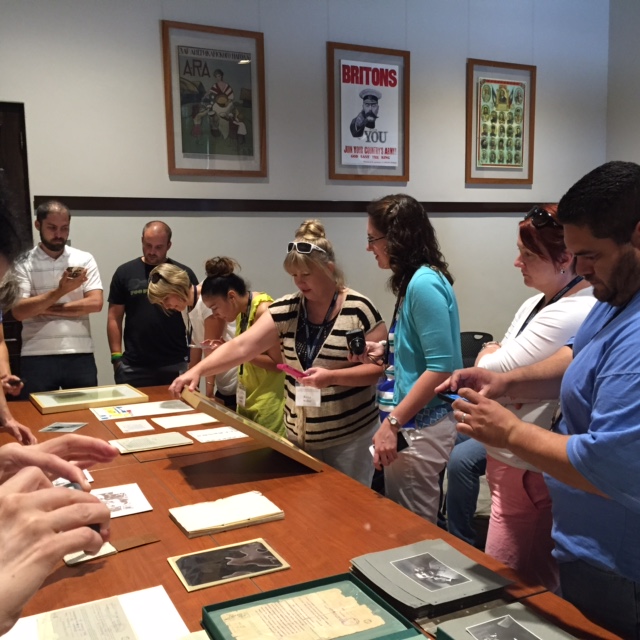

On June 25, high school teachers from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History visited the Hoover Library & Archives to view materials related to the Great Depression, the New Deal, and the economic and political policies before and during World War II. Hoover’s rich holdings in this area of study—spanning from the collection of Raymond Moley, the speechwriter who coined Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s famous program, to Mark Sullivan, a journalist fiercely opposed to what he termed the “The Roosevelt Road to Ruin”—illuminate the vast complexity of responses to FDR’s ambitious domestic relief program. FDR’s New Deal, now often considered to have saved the country during the dark hours of the Great Depression, faced vast opposition when it was introduced in 1933. Much like today’s opponents of the Affordable Care Act, New Deal detractors felt that FDR’s program would lead the United States toward socialism.

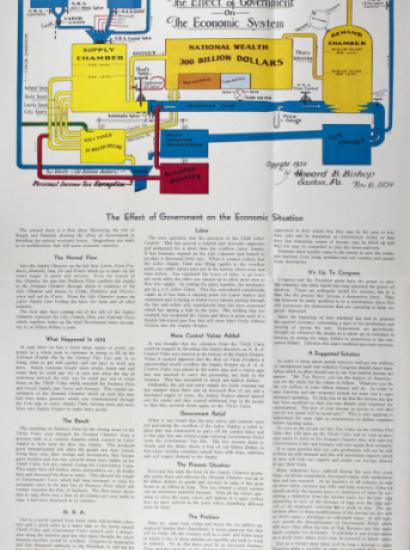

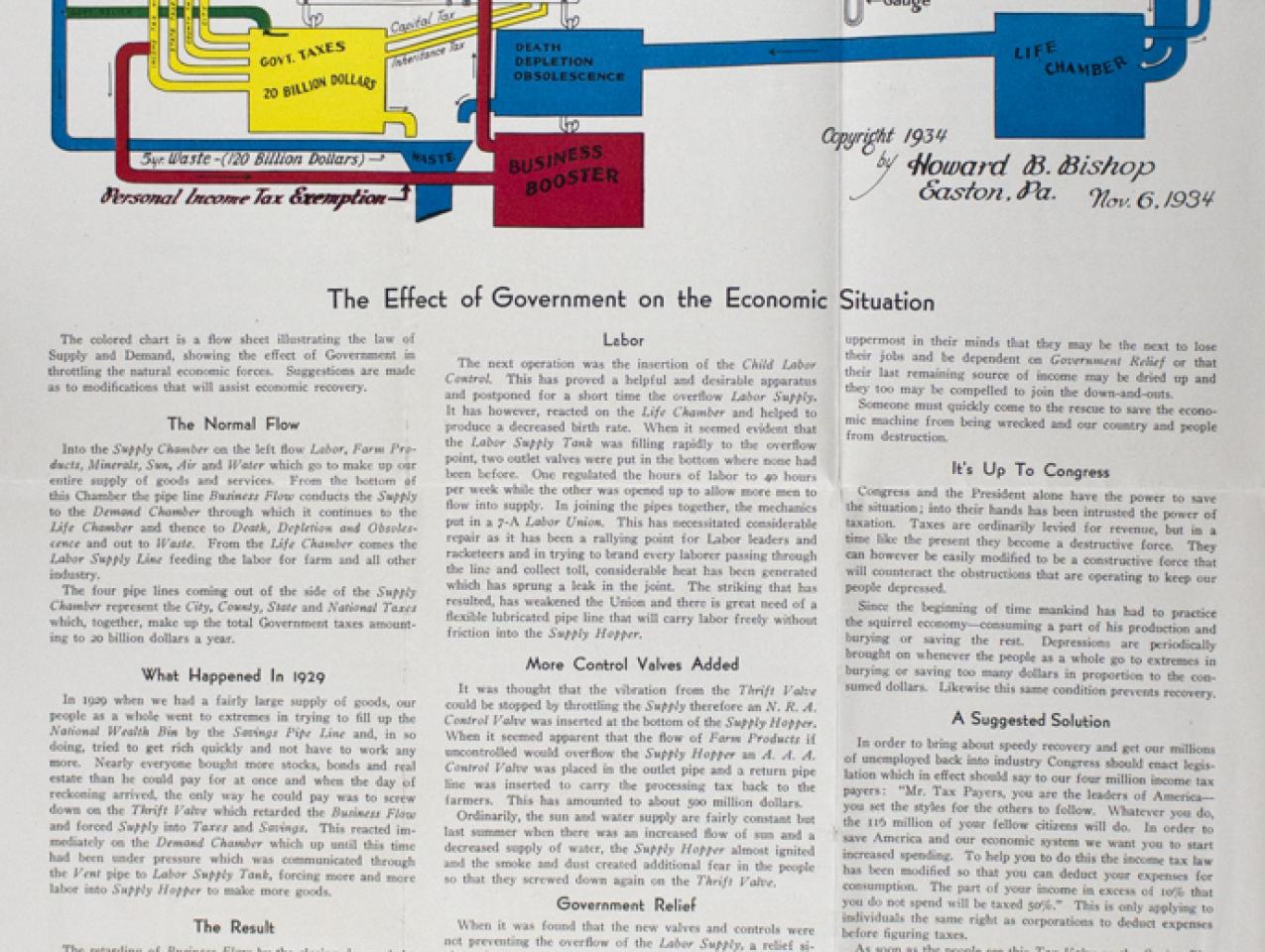

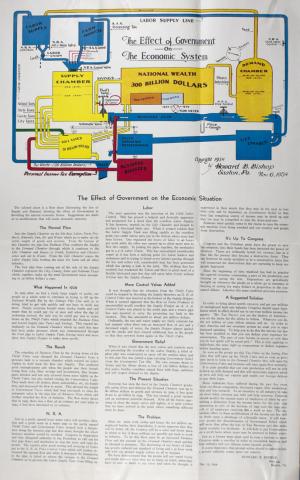

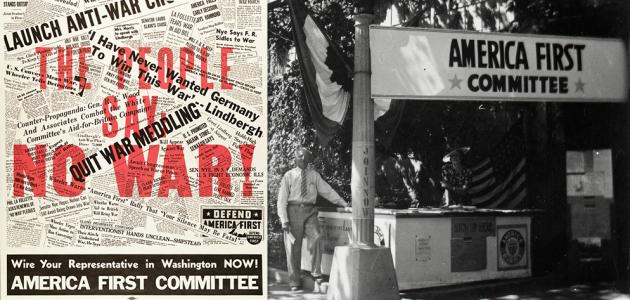

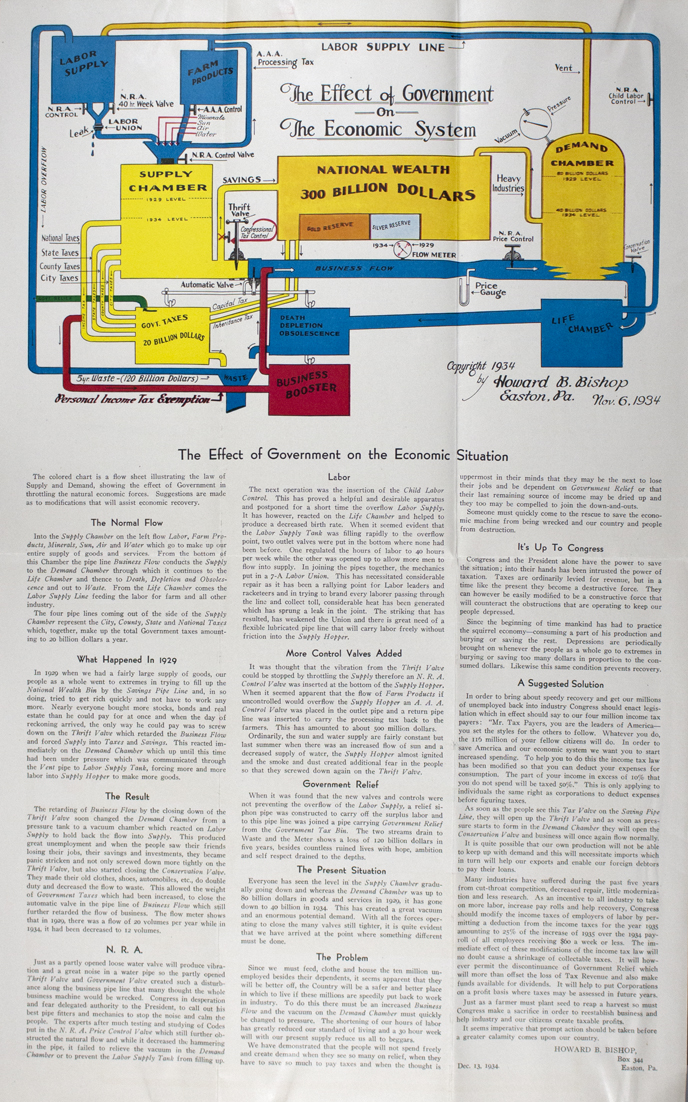

Of the numerous—and often humorous—New Deal materials viewed during the Gilder Lehrman visit, perhaps the most discussed were items from the archive of American journalist Mark Sullivan. Sullivan, a political columnist for Collier’s in the 1930s and a close friend of Herbert Hoover’s, was a staunch enemy both of New Deal policy and of Hoover’s political rival, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Sullivan’s archive proves him to be a precise, appreciative wordsmith as well as a bibliophile: the manuscript boxes in the archive contain heavily edited drafts of his own newspaper articles, as well as a collection of clippings, pamphlets, and ephemera that document a both artful and extensive opposition to the New Deal. What emerges as perhaps most remarkable in Sullivan’s vast array of anti-FDR materials is how frequently humor and satire were the vehicles through which commentators expressed their discontent with policies they feared were socialist. While viewing spoofs such as a poem titled “Alphabetically Speaking,” a farcical “1934 Psalm” that opens “Mr. Roosevelt is my shepherd/I am in want,” and a drawing of a Rube Goldberg machine that sends supply and demand through pipes, drains, and spigots, the visiting teachers found that the brand of humor used by these anti–New Dealers was akin to that used by artists such as Woody Guthrie, whose populist, Depression-era songs often combined humor with political commentary about the plight of the working class. Guthrie, who throughout the 1930s maintained ties with the American Communist Party, sympathized with the economic desperation of American citizens affected by the Depression, although he did not fully endorse the relief programs put forward by the Democratic Party. Guthrie’s “Do Re Mi,” for example, playfully warns poor migrants’ leaving Dust Bowl–blighted states that they can’t enjoy the Californian “Garden of Eden” without plenty of “dough”:

Oh, if you ain't got the do re mi, folks, you ain't got the do re mi,

Why, you better go back to beautiful Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Georgia, Tennessee.

California is a garden of Eden, a paradise to live in or see;

But believe it or not, you won't find it so hot

If you ain't got the do re mi.

The experience of the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression inspired poets, writers, and folk singers such as Guthrie to produce works both iconic and ironic, and commonly associated with leftist politics. Guthrie’s signature irony is often cited as a staple of an American folk tradition of populist sentiment that began with artists such as Guthrie and Pete Seeger and was handed down to a later generation of politically active artists including Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. As visitors from the Gilder Lehrman Institute found, however, populist-leaning folk artists of the 1930s did not maintain sole stylistic possession of satire as a tool to call for political change. The document in the image to the left, for example, is a poem that was read by New Jersey governor Harold G. Hoffman during a 1935 speech for the National Republican Club, during which he emphasized his constituency’s rejection of the proto-socialist underpinnings of the New Deal. Like Guthrie, the unknown author of the poem is preoccupied with money but blames FDR’s creation of bureaus and taxes for perpetuating the misery of the unemployed:

Unless these New Deal Democrats

Stope [sic] pulling bureaus out of hats,

I fear that soon we’ll have to get

A new and larger alphabet.

Now, what this country needs today

Is less and less of N.R.A.,

B.U.N.K. and E.T.C.,

But more and more of C.O.D.

For in the sweet bye and bye

Somebody has to P.A.Y.

For all this “Jack” the U.S.A.

Is handing out so free today.

Subsequent to reading the poem, Governor Hoffman reminded his audience that the Republican Party was initially organized to oppose human slavery and warned that the socialist liberalism of the New Deal introduced a threat to the personal freedom of Americans.

Thus, the archival record at the Hoover Institution bears out that the 1930s aesthetics of opposition spanned the political divide, with both right- and left-leaning activists fighting the Great Depression with humor and irony. As one of the visitors from the Gilder Lehrman Institute aptly commented, the Great Depression introduced a new society wherein all citizens, no matter what their political leanings, brought new meaning to the term “broke as a joke.” The slideshow in the sidebar highlights many items from the Hoover Library & Archives that document public reaction to the New Deal in the 1930s, including a draft of the speech wherein the term was first introduced.