By Kelly C. Tang

A few years ago, I watched a televised broadcast of the newly selected members of the Politburo Standing Committee taking the stage in Beijing’s cavernous Great Hall of the People. One by one, they each strode to assume their position before their peers and before the millions of Chinese watching from home. Omnipresent in every close-up, tracking shot, and zooming shot of the broadcast, was a large, mural-sized modern Chinese landscape painting in the background. The painting depicts tree-topped mountains in hues of tawny and bronze encircled by froths of air and lightness. It is a setting with specific visual resonance that transports these leaders far beyond the boundaries of a public ceremony in contemporary China into the realm of historic time and unbroken cultural continuity.

This modern Chinese landscape painting—and the countless others that serve as suitable backgrounds for official functions—is an essential part of the staging of twenty-first century China. But how did modern Chinese art come into existence? My dissertation research conceives of “modern Chinese art” as a traveler’s tale narrated by artists, journalists, and art historians as they wandered the world and confronted the reverberations of global upheavals in matters of war, nation, and ideology.

My investigation into some of these individuals led me to seek out the resources of the Hoover Library and Archives. During my research trip, I focused on three collections: Zhang Shuqi (1901-1957), Jack Chen (1908-1996), and Helen Foster Snow (also known by her pen name Nym Wales, 1907-1997).

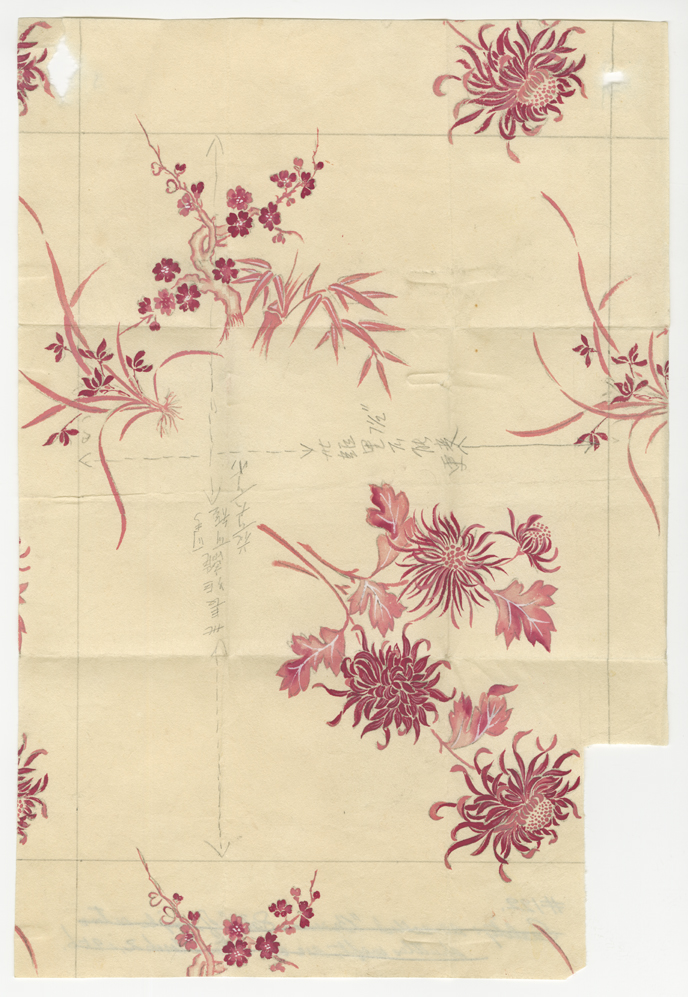

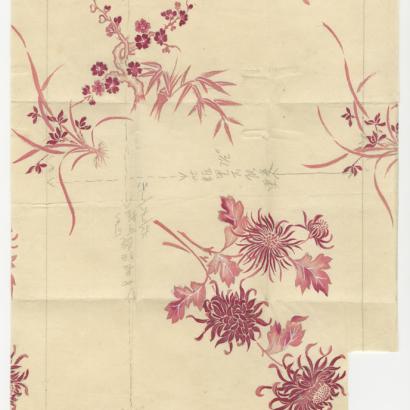

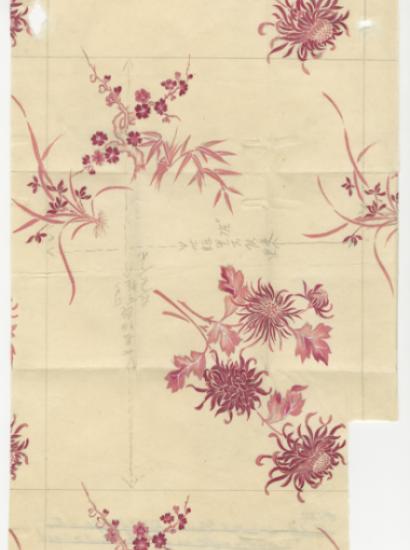

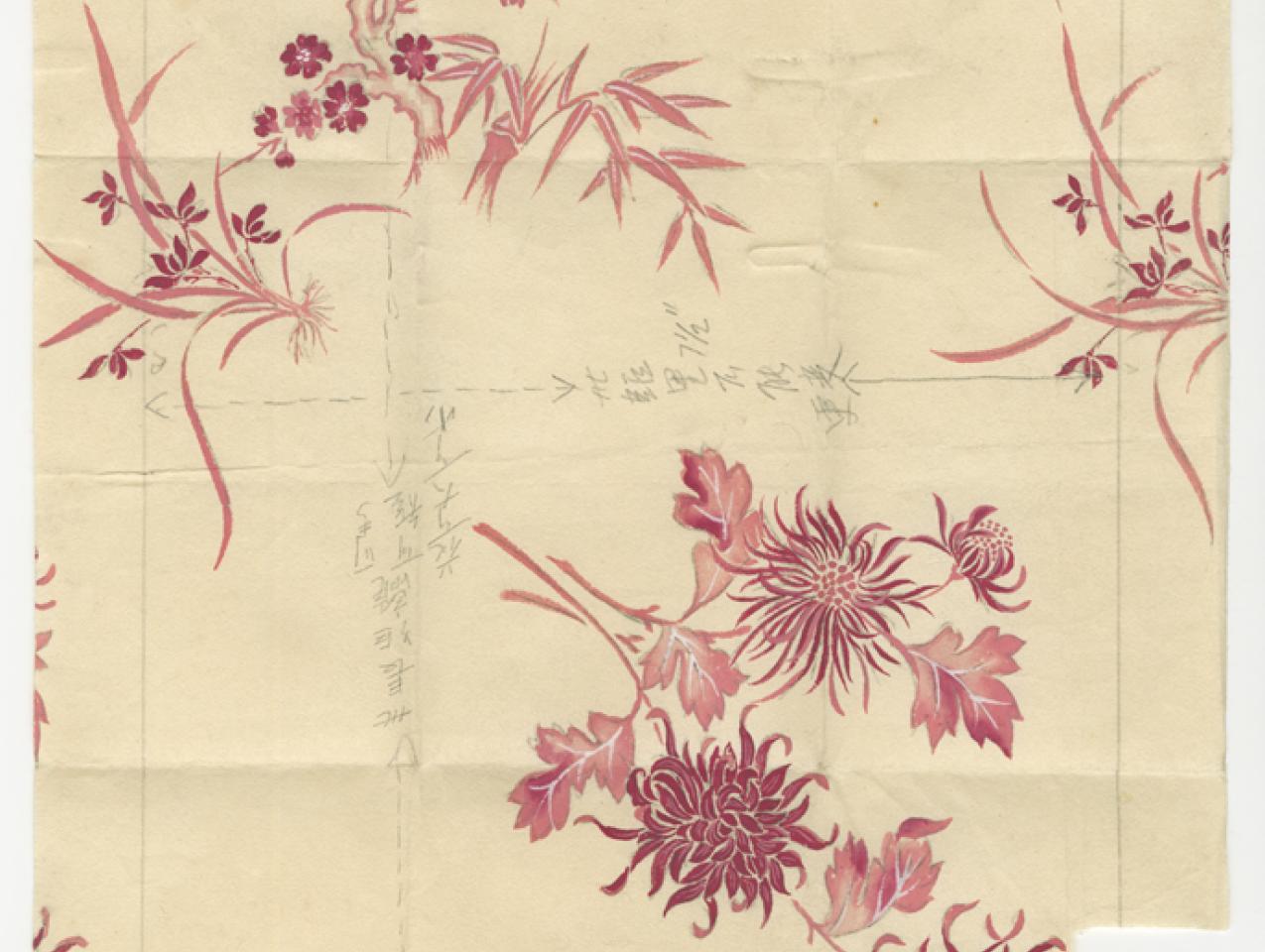

Zhang Shuqi was a well-known artist and art teacher who moved to the United States from mainland China by way of Taiwan. He has gradually become included as a voice in the historical development of modern Chinese art in recent years, but in the more marginalized domains of diasporic history. Numerous aspects of Zhang’s life and art—for example, his popular stationery sets that were sold across the country and his painting Messengers of Peace (1940), which was a commissioned gift from Chiang Kai-shek to President Franklin D. Roosevelt—speak to multiple conceptual levels of modern Chinese art that are absent in the present narrative of its history, even as its visual material continues to be evoked in the international arena.

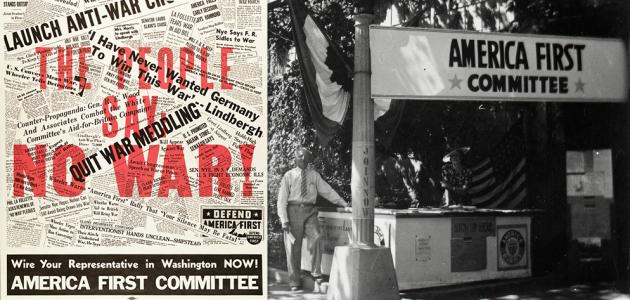

Unlike Zhang Shuqi, who has an identifiable role in art history, the figures of Jack Chen and Helen Foster Snow are overlooked. Jack Chen was a political cartoonist, journalist, and Sinologist of Sino-Caribbean descent that received art training in Moscow and published in China, the United States, and Europe. Frequenting the same publication circles as Chen, Snow (whose husband was Edgar Snow) wrote extensively on China and leftist politics. Her work Notes on the Left-Wing Painters and Modern Art in China (1961) and her collaborations with a Chinese artist identified as Wang Chun-Chu (1905-?) in her writings, have not been thoroughly examined for their contributions in modern Chinese art.

While I was accessing these archives at the Hoover, it was an unexpected surprise to be introduced to a cast of secondary figures. For example, Thomas Sgovio (1916-1997), an American artist that had followed his father to the Soviet Union for reasons of political asylum, was interrogated about Jack Chen while in Soviet gulags. There is also the mysterious artist Wang Chun-chu, Nym Wales’ artist friend, who gifted a painting as a wedding present to American author Pearl Buck (1892-1973). Finally, the touching letters between Zhang Shuqi’s wife Helen and Chiang Yee (1903-1977), popular travel writer and artist based in the United Kingdom, about their trans-Atlantic friendship and joint projects suggests how the relationships of wanderers was crucial to the project of formulating modern Chinese art.

My initial trip to the Hoover was essential to bringing these early research ideas into direct engagement with a definable set of texts and objects. As I continue to explore and connect these various individuals and their works to the larger body of scholarly work on modern Chinese art, I hope to uncover a different understanding of Chinese art history in the twentieth century that can facilitate similarly transnational research in other areas of art history, visual studies, and beyond.

I am grateful to the Hoover Institute Library and Archives for the Silas Palmer Fellowship and would like to express my appreciation for the wonderful staff that were so generous with their time and expertise. Carol Leadenham, David Sun, Jean Cannon, and Bronweyn Coleman were helpful and encouraging. Dr. Lisa Nguyen astutely pointed me to the fascinating Thomas Sgovio papers. Finally, in between archival work, I was fortunate to be included in Dr. Hsiao-Ting Lin’s five-day “China and Its Neighbors” workshop and engage with the vibrant intellectual community of the Hoover. I anticipate returning to the Hoover Institute Library and Archives in the future.