By Sam Premutico, Stanford Class of 2018

During World War I, the Ottoman Empire massacred more than one million Armenian citizens in what was condemned as “a crime against humanity” by Western powers; it is known today as the Armenian Genocide. Founded by the then–US ambassador to Turkey Henry Morgenthau and his colleagues in response to the slaughter, the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief published propaganda posters in a fund-raising campaign for humanitarian relief for victims of the genocide. With the backing of President Woodrow Wilson and subsequent presidents, the organization helped raise upward of seventy million dollars in funding for the cause over six years; it was later renamed the Near East Foundation (NEF).

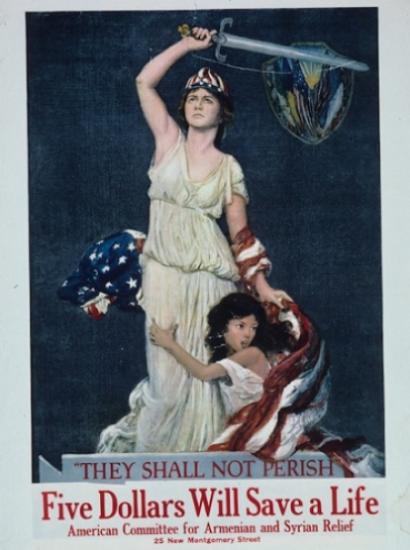

This poster is propagandistic in its use of rhetorical persuasion to further a cause. Through the portrayal of hyperpatriotism, contrasted body language, and careful textual placement, the poster identifies not a heroic cause for the viewer but a heroic self within the viewer. The poster alerts the viewer, a member of the American public, to an urgent injustice, then, through manipulation, allows the viewer to insert oneself as the heroic figure: the steadfast savior dominating the poster. Ultimately the poster persuades the viewer that the five-dollar donation is not a kind gesture or favor but a humanitarian obligation. To act on the duty should be expected; to not act would spurn the noble human being within the viewer’s self, fail the duties to the guardian nation, and ignore a moral necessity.

The American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief produced the poster for an American audience, using patriotism as a primary means of persuasion. The document’s patriotic appeals, in their most heightened and overblown form, help the viewer identify with the poster’s savior and reinforce the role of Americans as obliged to protect the weak. The prominent American flag intertwining the American guardian with the Armenian refugee perhaps best identifies the relationship between the two that its authors hoped to evoke. The flag’s role in shielding the refugee from her foes is clear, but the subtle way it flows and falls reveals more. Red and white stripes fall on the girl’s back, covering much of her body. The flag extends beyond the pedestal, or platform, the two are on and continues off the page, paralleling the United States’ massive capacity to defend and the viewer's capacity to share her or his wealth. The flag’s sturdy flow on the savior’s other side communicates the elegance the American maintains in defense. In between the two portions, however, lies the flag’s distinctive feature—the flag flies to the soldier’s back, not front, implying that as Americans, viewers need not be reminded of their nationality but can stand firm in battle, knowing the defense afforded to them by their homeland—a luxury not granted to Armenian refugees. The subtlety pushes viewers to not only stand content with their security but also provide it to others. In doing so, viewers recognize the necessity of action and the obligation to share with others the luxury of that security. Similarly, the American flag–coated helmet the soldier wears reinforces the disparity in security afforded to the soldier—and thus the viewers—and the Armenian refugee. Not only does the helmet demonstrate the source of security in its decoration, but the presence of a helmet in contrast to the refugee’s lack thereof awakens viewers to the luxury of their security. The poster’s use of patriotism culminates with the faded shield-like emblem in the upper right corner. Although the individual flags are hard to distinguish, the American flag stands in front. As the sun rises behind it, the viewer can’t help but infer the overtly symbolic dawning of a new day. As the poster’s hero wields her weapon, the sword covers the emblem’s ensemble of flags, employing the role of America as a global protector of the weak. The multiple appeals to patriotism let the poster’s savior exist not as a discrete individual but as a template that any American can fill. If US security propels the steadfast soldier, viewers can logically fit the part as well. Thus patriotism acts as a bridge connecting the audience to the poster’s heroic figure, allowing the viewer to inhabit the soldier.

Through a contrast in posture and body language of the savior and the saved, the poster asks the viewer to adopt a notion of duty by emphasizing the ease of protecting the refugee for an American and the insufficiency of self-defense for the Armenian. The refugee grips tight the leg of the soldier as a child would a parent—an intentionally paternalistic representation of the United States’ and, in turn, the viewer’s role in the conflict. The appeal to parenthood evokes empathy and action from viewers, who could quickly identify with and thus embrace the role. The poster’s contrast of facial expression is clear but its implications subtle. The refugee, pulling herself tightly one way, looks horizontally back at her supposed enemies, her open mouth illustrating her worry and fright. The American soldier, however, wears a stern face, ignoring the enemies on her left as she looks upward, not to the side, intimating her cause is greater than the enemies she guards against—lofty in its aim, noble in its execution. The direction of her glance implies her enemies are not worthy of her concern, for her nation secures and strengthens her. Furthermore, the clothing of the Armenian refugee compared to that of the American soldier inserts a dichotomy, maintaining or lacking elegance in the face of opposition. Similarly, the refugee’s hair is disheveled, whereas the American soldier’s is held by her helmet. The contrast in body types clearly marks a contrast in nourishment, increasing the need for donations. The American stands tall and confident, a well-nourished, sturdy soldier; the refugee has a much more frail, comparatively malnourished figure. Ultimately, the contrast in figure and body language unite to portray the American as steadfast and noble in pursuit of justice and his capacity to help the frail refugee.

Finally, the careful placement of the poster’s limited text makes the viewer feel as if donating is not an option but a duty. The text is in two discrete planes; the inscription “They Shall Not Perish” decorates the pedestal holding the soldier and refugee in the frame; the poster’s call to action stands outside the action’s frame, along with the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief’s recognition of authorship. If the discrete planes denote the separation of the reality and potential reality of the situation (the protection of Armenian refugees) from the means to that end (the requested donation), then the textual planes manipulate the viewer’s perception of the donation’s dutiful nature.The spatial manipulation renders the assertion “They Shall Not Perish” a fact of reality and moral necessity, yet realizing the protection is contingent on the viewer’s participation. Failure to realize the poster’s call to action would then equate to accepting an immoral course of action. Inaction is then not a passive act of indifference but willful and active ignorance.

The American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief’s manipulation of patriotism, figure, and textual symbolism does not tell its audience to act but inspires in that audience a sense of duty to act. A viewer identifies disparities between the two subjects, recognizes the capacity of the self to lessen the refugee’s struggle, and convinces oneself that there was no option to start with but only a duty. Thus, the viewer is no mere benefactor of a soldier for hire; the viewer is the soldier, the donation his sword.