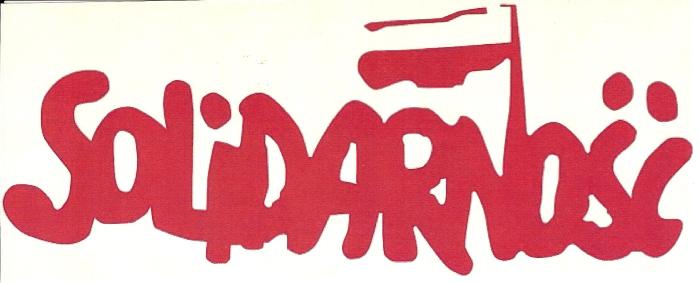

Above: Masthead illustration of the Solidarity logo: Solidarność

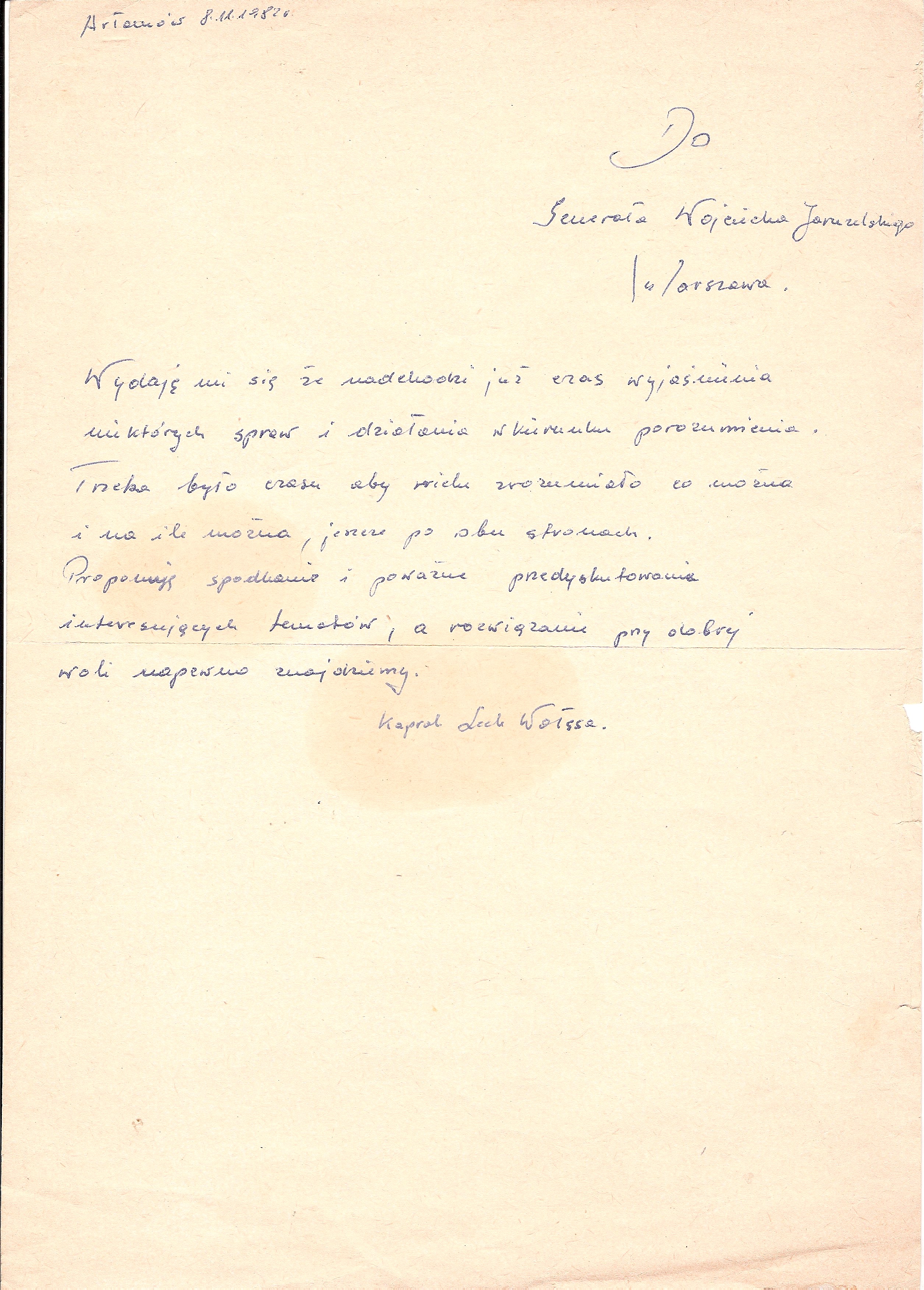

The original copy of the most celebrated Polish letter of the 1980s has surfaced in the Hoover Institution Archives. This three-sentence note by the Polish Solidarity trade union leader and the 1983 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Lech Wałęsa, was written from his internment to Poland’s communist prime minister, General Wojciech Jaruzelski. Because Walesa signed it, ironically, “Corporal Lech Wałęsa,” Polish historians have dubbed it “a corporal’s letter to the general.” The letter was found in the miscellaneous papers of Poland’s last communist minister of the interior, general Czesław Kiszczak, which were received by Hoover in May of this year from the family of the minister, who died in November 2015. After preservation treatment and processing, Wałęsa’s letter and the other papers, as well as more than a thousand photographs and numerous videotapes, will be added to the small Kiszczak collection already in the Archives.

The Soviet Bloc of the late 1970s was undergoing serious economic and political problems. As the crisis continued to worsen, voices calling for reform and fundamental change of the system became forceful. Poland was the first country in the bloc where, by 1980, a mass opposition movement had emerged. Founded during a strike in the Lenin Shipyard of the city of Gdańsk, it took the name of Independent Self-governing Trade Union Solidarity (Solidarność). Its leader, Lech Wałęsa, was a charismatic young electrician; its membership had reached ten million by late 1981, making it the largest labor union in the world. With the situation escalating out of the communists’ control, General Wojciech Jaruzelski imposed martial law on December13, 1981. More than ten thousand dissidents and Solidarity activists were interned in special camps and prisons. Officially, Wałęsa was not imprisoned but considered a “guest” of the communist regime, spending eleven months in several government resorts, the last of these being Arłamów in the far southeastern corner of Poland near the Soviet border. It was here that the chairman of Solidarity wrote his famous letter:

Arłamów Nov. 8, 1982

To

General Wojciech Jaruzelski

Warsaw

It seems to me that a time is approaching for clarification of certain matters and for working toward an understanding. There has been some time for many on both sides to understand what can be done and how much can be done.

I propose a meeting and serious discussion of subjects of interest, and with goodwill we will find a solution.

Corporal Lech Wałęsa

The letter is written in Walesa’s characteristic style, including spelling mistakes. The Solidarity leader preferred to address Jaruzelski as general rather than prime minister, probably to emphasize the fact that Poland was being governed under martial law. Having decided that, he chose, not without irony, to recall his own modest military rank, which he earned during army service in the early 1960s, rather than that of presiding officer of the largest trade union in the world.

The motivation, the timing, and the form of the letter have all received attention from historians. There is no unanimity. Some suggest that it may have been inspired by communist security services, with which Walesa collaborated to some extent during 1970−76, and which held secret documentation of those contacts, a powerful tool for potential blackmail of the Solidarity chairman. Wałęsa himself claimed that it was the idea of his wife who had visited him in Arłamów only several days earlier. Be that as it may, Poland was at a standstill; neither the communist regime nor the Solidarity Union was gaining ground, with political repression, economic near-collapse, massive food shortages, and another harsh winter looming. Wałęsa's note broke the stalemate. The letter was immediately faxed to Warsaw to the general and the original filed in Kiszczak’s papers. Jaruzelski immediately consulted with his deputy premier, Mieczysław Rakowski; those meetings are covered in detail in Rakowski’s voluminous diaries, originals of which are also in the Hoover Archives. The next day, November 10, was marked by the long-awaited death of the Soviet Bloc’s supreme overlord, General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, emboldening Poland’s top communists to act without further delay. Wałęsa was released on November 11, which coincidentally was the Polish Independence Day, a national holiday celebrated before World War II and eliminated by the Communists.

Nevertheless, in late 1982 independence for Poland was neither imminent nor inevitable. It took six more years of determined struggle by the great majority of the Polish nation, as well as the moral and material support of powerful international allies − Poland’s native son John Paul II, President Reagan, and Prime Minister Thatcher − to keep the independence project alive. It also took the third successor to Brezhnev, Mikhail Gorbachev, and his futile effort to reform the Soviet system, which unintentionally led to further weakening of the cohesiveness of the Soviet Bloc, an opportunity taken advantage of by the Polish opposition and political dissidents in neighboring countries. Wałęsa, who throughout this time was closely watched by the security services, was the universally recognized leader of the Polish struggle, though his leadership was more symbolic than direct. Solidarity’s victory in the semi-free elections of June 1989, Poland’s first after nearly fifty years of foreign domination, showed the total bankruptcy of the communist regime. It also provided an example for the other peoples of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to follow.

Hoover Library & Archives have the largest and most comprehensive holdings on twentieth-century Poland outside Poland. These are especially rich for the period of the 1980s. They include the papers of anti-communist opposition activists as well as communist functionaries. Hoover’s collection of Polish independent publications of the 1976−90 was for many years the most comprehensive in the world and is still consulted by researchers from Poland.

Maciej Siekierski

Siekierski@stanford.edu