Statement by John Raisian, the Tad and Dianne Taube Director of the Hoover Institution:

The Hoover Institution, today, mourns the loss of a great historian and friend, Robert Conquest. It is with profound sadness that we reflect upon his life and intellectual contributions, which have left a lasting impression around the world. Our thoughts and prayers are with his loved ones during this time.

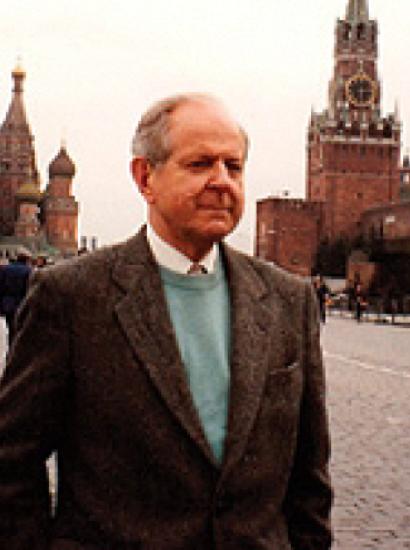

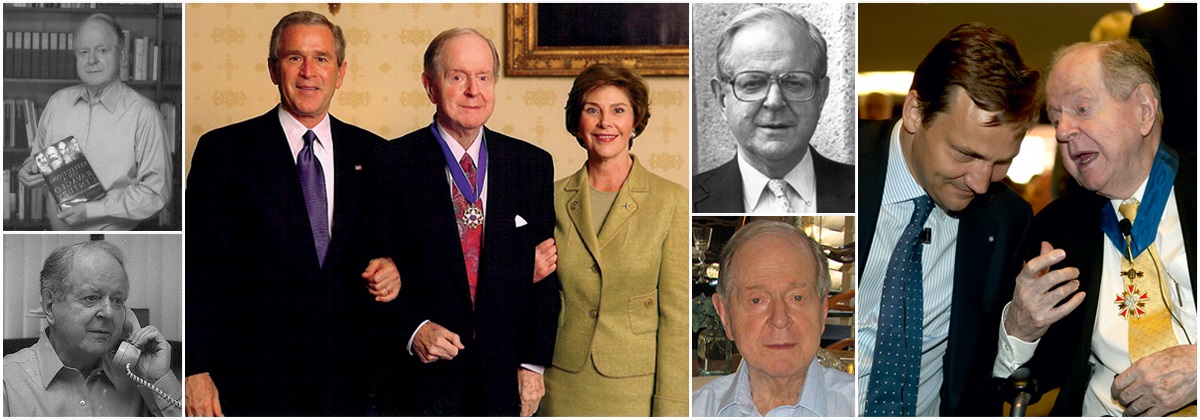

Conquest spent 28 years at the Hoover Institution where he was a Senior Research Fellow. A recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005, he was a renowned historian of Soviet politics and foreign policy. Conquest has been known for his landmark work The Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the Thirties. More than 35 years after its publication, the book remains one of the most influential studies of Soviet history and has been translated into more than 20 languages.

Other awards and honors include the Jefferson Lectureship, the highest honor bestowed by the federal government for achievement in the humanities (1993), the Dan David Prize (2012), Poland's Commander's Cross of the Order of Merit (2009), Estonia's Cross of Terra Mariana (2008), and the Ukrainian Order of Yaroslav Mudryi (2005).

Conquest was the author of twenty-one books on Soviet history, politics, and international affairs including Harvest of Sorrow, Stalin and the Kirov Murder, The Great Terror: A Reassessment, Stalin: Breaker of Nations and Reflections on a Ravaged Century and The Dragons of Expectation. Conquest was literary editor of the London Spectator, brought out eight volumes of poetry and one of literary criticism, edited the seminal New Lines anthologies (1955–63), and published a verse translation of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's epic Prussian Nights (1977). He also published a science fiction novel, A World of Difference (1955), and is joint author, with Kingsley Amis, of another novel, The Egyptologists (1965). In 1997 he received the American Academy of Arts and Letters' Michael Braude Award for Light Verse.

Educated at Winchester College and the University of Grenoble, he was an exhibitioner in modern history at Magdalen College, Oxford, receiving his BA and MA in politics, philosophy, and economics and his DLitt in history.

Conquest served in the British infantry in World War II and thereafter in His Majesty's Diplomatic Service; he was awarded the Order of the British Empire. In 1996 he was named a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George.

TRIBUTES:

✦ George P. Shultz, Hoover Institution Thomas W. and Susan B. Ford Distinguished Fellow and Former Secretary of State

Robert Conquest set the gold standard for careful research, total integrity, and clarity of expression about the real Soviet Union. He taught us all and he will live on in that spirit.

✦ Robert Service, Hoover Senior Fellow

Robert Conquest was full of life, despite his physical frailty, through to the end, and we're all going to miss him greatly. He was a tireless investigator of Stalin's tyranny. His Power and Policy in the USSR was a landmark, conceptually and empirically, in the analysis of Soviet totalitarianism; it was all the more remarkable since he had to glean a lot of his data from that most unpromising source, the Moscow newspaper Pravda. Just as extraordinary was his Great Terror. It was Bob who invented the term to describe the appalling inhumanities perpetrated by Joseph Stalin against his own countrymen and others in their millions. In Harvest of Sorrow he gave a voice to the Ukrainian peasants who starved to death under the impact of agricultural collectivization. In these and later books, he became recognized for his scrupulous attention to factual detail while providing a searing account of the travails of Russia and its borderlands. When he updated The Great Terror for its later editions, there was little he needed to alter in the general picture.

In postwar Britain he was as much a literary figure as a historian. His poems were read out in English secondary-school classes as exemplars of the new clear-writing style that repudiated verbal abstruseness. His verse, like his historical prose, was limpid and engaging. As recently as the collection titled Penultimata he produced brilliant poetry - much of it dedicated to the biggest questions of life and death - that will survive any test of posterity.

People loved his impish sense of humour - in his younger days he was a dedicated practical joker. Grim though his works on history and politics could be, he himself was full of a joie de vivre. He was a handsome fellow, always well-turned out and ready for a jolly evening after a day's work. His close friends included several of the literary giants of the decades after the second world war such as Anthony Powell, Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin. With his lovely wife Liddie, who looked after him splendidly in his declining years, he was always an engaging host. Nobody visited their home without coming away with a store of anecdotes.

And what a campaigner he was. Firm of conviction and excellently informed, he provided countless politicians including Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher with guidance about the roots of the USSR's policies around the world. He was equally eager to talk to younger generations. Robert Conquest produced work of fundamental importance that will always be read. Born in the year of the October Revolution, he outlived the Soviet totalitarian experiment by many years. He was a towering political and literary figure who made a difference to the turbulent times that he witnessed.

✦ Stephen Kotkin, Hoover Research Fellow and Birkelund Professor of History and International Affairs, Princeton University

Robert Conquest (1917-2015) published some thirty books of history and policy, and six of poetry, establishing himself as the most prolific, most influential Sovietologist ever. Two of his books on Soviet history stand out as the most important of the entire cold war.

The Great Terror (1968) was a blockbuster in all senses. At a time of doubt and controversy about the menace of Communism, Mr. Conquest massed a mountain of detail and definitively established the vast scale of Soviet terror, and Stalin’s central role in it. Now this is taken for granted. Soviet archives were closed and Soviet publications full of lies, yet he was criticized for relying on the large number of émigré memoirs and the unpublished reminiscences in the Hoover Institution Archives. Mr. Conquest insisted on the validity of the accounts of the victims. The opening of the archives has shown that by and large he was correct. He also made meticulous Kremlinological use of Stalin-era newspapers, and systematically combed through the voluminous “thaw” or Khrushchev-era Soviet publications, which were often very revealing. The leftist slant of Soviet studies in the U.S. limited the acceptance of Mr. Conquest’s scholarly work, even as he dominated discussion among the public and policy-makers. In the late stages and aftermath of the Soviet Union, The Great Terror, translated into Russian, became the most widely influential Western publication on Soviet history in that country. Mr. Conquest pulled off a similar feat with The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine (1986), written here at Hoover. Once again, he definitively established the colossal scale of Soviet horrors, correctly identified their source in Marxist ideas and practices, and underscored the legions of Western dupes who retailed Soviet lies, from when Stalin was alive and decades thereafter.

I first met Mr. Conquest in the archive reading room at Hoover, in the mid-1980s, when he was already a legend (I was a Ph.D. student at UC Berkeley). He had sparkling eyes and a wry smile, and relished chatting about obscure sources and discoveries. In November 1987, I had the privilege of serving as his Russian language translator at the annual convention of the American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies Convention in Boston. (Mr. Conquest spoke fluent Bulgarian from his service in the British legation in Sofia and one of his marriages, but did not speak Russian conversationally, although he read it fluently). His interlocutor that day was the writer Anatoly Rybakov, who was enjoying wide acclaim for his novel Children of the Arbat, but effervescing over meeting the great Bob Conquest. “Is it true,” a spellbound Rybkaov kept asking me, “that he also writes poetry?”

✦ Paul Gregory, Hoover Research Fellow

Robert Conquest died today in Palo Alto, California at the age of 98. In addition to being a noted poet and writer of memorable limericks, Conquest wrote two of the most influential works on the history of Stalinist Russia – The Great Terror (1958) and The Harvest of Sorrow (1986). His Great Terror was the first to describe the magnitude and horrors of Joseph Stalin’s repressions, which killed not only thousands of the state and party elite, but executed and imprisoned millions of ordinary people who had done nothing wrong. His Harvest of Sorrow described the Stalin-made famine that accompanied the forced collectivization of agriculture and that needlessly killed millions of Russians, Ukrainians, Kazakhs, and other peoples of Russia. Robert Conquest somehow pieced together his two historical masterpieces out of scraps and bits of information from émigrés, newspaper accounts, and statistical publications that remarkably allowed him to penetrate the deepest secrets of the Soviet Union as a lone researcher. He was an ardent supporter of collecting microfilm of the secret archives of the Soviet Communist Party after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a project conducted by his own Hoover Institution Library and Archives. Robert Conquest was widely attacked by the British and American left for his “exaggerations” of the excesses of Soviet communism, but subsequent research in the official Soviet archives substantiated the accuracy of his brutal accounts of the USSR. Remarkably, he was able to issue new editions of the Great Terror in 1990 and 2008 leaving the basic contents largely untouched from the original edition. Robert Conquest was deeply disturbed by the so-called revisionist historians, who somehow argued that Joseph Stalin was simply responding to what Soviet society and his regional underlings demanded of him. His irritation rose as evidence of Stalin’s micromanagement of mass killings was revealed in official documents, such as the famous “shooting lists” and Stalin’s signature on the telegrams that set in motion the “mass operations” of 1937 and 1938. Robert Conquest remained an active scholar after his retirement. The Hoover Institution arranged for research assistants to deliver the latest materials from the Soviet archives to him on a weekly basis. Visitors, bearing tidings of new findings, were surprised to learn that he knew this information already. Well past his 90th birthday, Robert Conquest and his wife Liddy received guests in their home to engage in animated discussions of poetry, history, and tales of the shenanigans and pranks of his literary circle “The Movement.” On an interesting historical note, Bob enjoyed relating his conversations with Margaret Thatcher on the economy and communism as she prepared herself for Britain’s highest political office. Today marks the passing of a giant.

✦ Bert Patenaude, Hoover Research Fellow

The long and full life of Robert Conquest—poet, historian, Cold Warrior, and much more—deserves to be warmly celebrated. I was introduced to Bob shortly after I arrived at Stanford in the fall of 1978 to begin my doctoral studies in history. For a young student of Russia and the Soviet Union to meet the author of The Great Terror was no minor event, and I was a bit nervous about it, but Bob's friendly and unassuming manner quickly put me at ease. And as the conversation came to an end he responded to my "Thank you, Dr. Conquest" with a generous "Call me Bob."

Those were the days when most scholars in Soviet studies regarded Conquest's works on the USSR with skepticism at best, and often outright hostility. In "the field," The Great Terror, was widely perceived as an ideological polemic that would not stand the test of time. Bob loathed political correctness, and he scorned those who professed to seek "balance" in their scholarly publications about Soviet history—"How do you find balance in mass murder?" He enjoyed dismissing such people as "wafflers." The collapse of Soviet Communism brought revelations from the Kremlin archives that bore out Bob's general view of Stalin's USSR, and he had the great pleasure of publishing a new version of the book in 1990, at the moment of his vindication. The revised version was called The Great Terror: A Reassessment, but most reviewers of the book recognized that it was in fact an emphatic reassertion of the original thesis rather than a revision.

Among his considerable gifts, Bob was a superb conversationalist. He had a wicked sense of humor and he loved to laugh: the look of playful delight that animated his face as he nailed a punch line is impossible to forget. His poems and limericks convey a sense of his mischievousness—and naughtiness—and his late poems chronicle the aging process with sensitivity and, one is easily persuaded, acute psychological insight.

Bob's final speaking appearance on the Stanford campus may well have been his participation in an annual book event, "A Company of Authors," where he came to present his latest book of verse, Penultimata, on April 24, 2010. Bob seemed frail that day, and at times it was difficult to hear him and to understand his meaning, but no one in the room could doubt that the genial elderly man up there reciting his poetry could have carried the entire company of authors on his back. Seated next to me in the audience was a Stanford history professor, a man (not incidentally) of the political left, someone I had known since my graduate student days—not a person I would ever have imagined would be drawn to Bob Conquest. Yet he had come to the event, he told me, specifically in order to see and hear the venerable poet-historian: "It's rare that you get to be in the presence of a great man. Robert Conquest is a great man." Indeed he was.

✦ Anatol Shmelev, Hoover Research Fellow and Curator, Russia and Eurasia Collection

Robert Conquest’s The Great Terror, which first appeared in 1968 and withstood many editions, was his most widely known and monumental contribution both to scholarship and to the West’s struggle against communism. Based on a close reading of all the sources then available, Conquest traced in detail the events, decisions and personalities involved in Stalin’s purges and the system of terror that marked his rule. To call the evidence of Stalin’s terror available to scholars at that time incomplete would be a massive understatement. Moreover, the evidence that was available, culled not so much from Soviet official sources as from accounts by defectors and emigres, was often contradictory and unreliable. But such was the brilliance of Robert Conquest’s intellect and the precision of his intuition that he was able to sift through the available sources, ascertain their value, weigh their reliability and contextualize them in such a way as to create a work of scholarship that retained validity in all its major arguments to the present day. This is a rare achievement for scholars even with full access to open archives, and therefore all the greater considering the obstacles present in the 1950s and 1960s.

For decades Conquest’s work – and in particular The Great Terror – stood as a warning and reproach to those in the West who would seek to justify the Soviet regime and communist ideology. In the Soviet Union itself The Great Terror circulated illegally as Samizdat and Tamizdat (a Russian translation, issued by an Italian publisher, was designed in height (17 cm.) to be easily transportable into the USSR, but at over 1000 pages, despite the thinness of the paper it was still a massive work and hard to smuggle in).

The Great Terror, like other of Conquest’s works, was subjected to heavy criticism in the 1980s by revisionists who felt that he had overstated the role of the regime and of Stalin himself in orchestrating the terror, but the opening of the Soviet archives in the late 1980s and 1990s vindicated Conquest and his argument, leaving historians by and large only the duty of verifying small details and retallying the actual figures of victims. Conquest wrote in the preface to the 1990 edition of The Great Terror: A Reassessment, “while the new material extends our knowledge, it confirms the general soundness of the account given in The Great Terror. And while in this reassessment I have thus been able to give a greatly enhanced account of these years, I have not made any changes for their own sake.” In private conversation, however, he said that the title of this book should have been “I told you so, you (vulgarity omitted) fools.”

Robert Conquest was not only a brilliant scholar, but a true gentleman, who went out of his way to make everyone who visited him for advice, conversation or just an autograph feel welcome. The bearer of a high intellect, Conquest could be very down-to-earth, full of entertaining anecdotes and stories, and always not only willing to hear out his guests, but actively engaging them with questions. His charm was genuine and born of a sense of humility that won over those who knew him. Though he was the recipient of many high awards and honors, including the Order of the British Empire, the title he most liked to recall was that of Antisovetchik nomer 1 (“Anti-Soviet #1”), an appellation bestowed upon him by the Soviet propaganda apparatus. This was, perhaps, because the title cut to the core of who Robert Conquest was: a champion of human freedom and a sworn enemy of oppressive and totalitarian regimes and the ideologies that stood behind the tragedies of the twentieth century.