The principal purpose of Operation “Enduring Freedom,” (OEF) as the Pentagon dubbed its response to the attacks of September 11, 2001, was to strike at the core of Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. However, OEF quickly reproduced itself in several other countries, reflecting the fact that, while al-Qaeda’s headquarters might have been in the Hindu Kush, it was in fact a global organization.

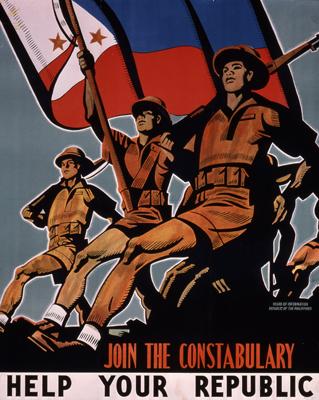

At least one OEF offspring also proved to have a larger strategic purpose. In the Philippines, it not only was the framework for assaults on the Abu Sayyaf organization, but also became a way to begin to repair the larger and long-enduring strategic partnership between Manila and Washington. What began in 1898 and survived through World War II and Vietnam had come to a surprise and slightly shabby end in 1991, the victim of negligence on the part of both governments and nationalistic pride in the Philippine Senate. But back then, with the end of the Cold War and the economic “tigers” of Southeast Asia on the rise, the Philippine-American alliance appeared anachronistic, even paternalistic. The giant bases at Clark Air Field and Subic Bay were shuttered by the end of 1992, the least controversial part of the first Bush Administration’s global reduction of U.S. military posture abroad. The eruption of the Mount Pinatubo volcano had blanketed the bases in ash, and then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney huffed that America was happy to leave “if we’re not wanted.”

Abu Sayyaf was not merely an al-Qaeda—and now Islamic State—franchise but a descendent of the Moro insurgency by the Muslims of the southern islands in the Philippine archipelago. The group was—and remains—especially vicious even by jihadi standards. It specializes in kidnapping both Westerners and Filipinos. But U.S. and Philippine special operations forces forged a remarkably effective and sustained campaign that has done much to rebuild strategic trust, trust that had deepened in recent years as the Chinese military has encroached on Philippine sovereignty across the South China Sea. Increasingly, Marine and other U.S. conventional forces have conducted joint exercises and employed bases—albeit on a “temporary” basis—in the Philippines. And more than $400 million worth of arms transfers have helped to modernize poorly equipped Philippine forces, very much outgunned by the People’s Liberation Army. Slowly, the unhappy break-up of the 1990s was forgotten.

Thus, few took notice when the Philippine version of OEF came to a formal end in late 2015; although a few American commandos remained on Mindanao—the main refuge and area of operations for Abu Sayyaf—the focus of military cooperation had shifted toward China. And the surprise announcement by new Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte that U.S. troops on Mindanao “have to go” looks as though it might herald a larger and hugely problematic rift. The enigmatic and violently hot-headed Duterte thrives on confrontation and as his indiscriminate “anti-drug” campaign careens out of control and results in a mounting number of extrajudicial killings, it begins to look like he’s flirting with the kind of Philippine nationalism that is deep-seated but sometimes self-defeating.

Beyond counterterror and counterinsurgency interests, Duterte’s erratic pronouncements are threatening to erode the common effort to counter Chinese expansionism. “China is now in power, and they have military superiority in the region…. We are not cutting umbilical cords, but I also would not want to place my country in jeopardy,” he declared in ending not only Abu Sayyaf patrols but joint naval patrols in the South China Sea. Despite obtaining a favorable ruling in July from the international Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague, Duterte seems to be walking away from Manila’s claims against China’s in the region. He’s also flirted with the idea of buying weaponry from Beijing and the Russians.

To be sure, the maverick Duterte is an outsider and something of an outlier in Philippine politics. And he has been notoriously loose-lipped, calling President Obama the “son of a whore” even as Obama was making his final trip to Asia, scuttling a planned stop in Manila. But the costs of unbridled nationalism now are far greater than in 1991, for the Philippines, for the United States, and for the prospects of peace and stability across East Asia.