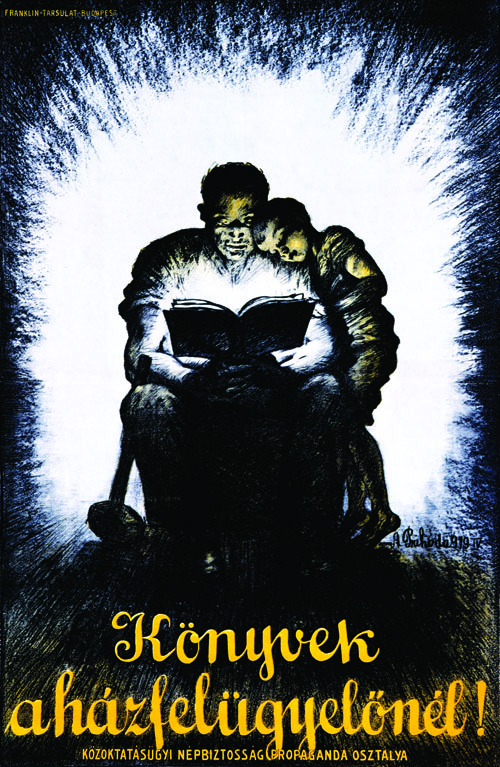

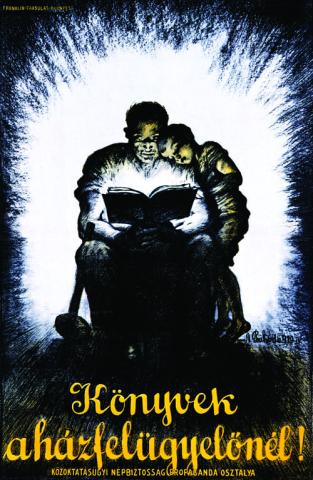

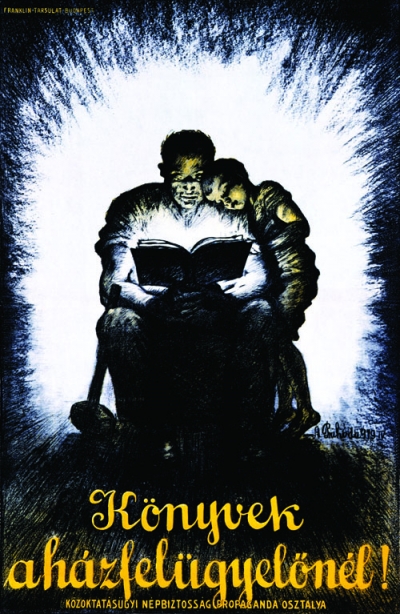

The early communist era was not known for gentle imagery. Propaganda posters overflow with blood, violence, macabre caricatures, shaken fists, and revolutionary shouting. That is why this poster, commissioned during the brief existence of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919, is so striking. It depicts a man and a boy, huddled together rather pleasantly, in the glow of a book that drives away the darkness. Its slogan is mundane: “The books are with the superintendent.” And yet this drowsy summons to literacy was part of a forceful, carefully tended philosophy. To read was to be taught; to be taught was to become a citizen and soldier of the new, communist world.

“The laboring masses thirst after education,” proclaimed Anatoly Lunacharsky, a writer and art critic who became Soviet Russia’s first people’s commissar of enlightenment. Besides promoting approved art and culture, his Commissariat of Enlightenment created “agitprop”—images to teach and prod the masses. “Red Army men looking at posters before battle . . . fight not with a prayer but with a slogan on their lips,” mused poet and playwright Vladimir Myakovsky, an agitprop creator.

Meantime, Europe witnessed the birth of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, the first communist regime in the Russian mold. It was to last not quite five months. It began on March 21, 1919, when Béla Kun overthrew Mihály Károlyi’s democratic government, itself only four months old. Eventually, Hungary’s counterpart to Lunacharsky emerged: Jozsef Pogány, a former high school teacher and war correspondent, now people’s commissar of education. During the brief communist reign, Pogány’s commissariat churned out 680 different propaganda leaflets and handbills promoting art, literature, education, and culture.

Among them was this poster, the creation of Transylvania-born artist István Azary Prihoda (1891–1965). Prihoda was an illustrator and copper engraver who studied at the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts. The poster was printed by the Franklin Society Press, a Budapest publishing group.

A man and a boy huddle together with a book in this literacy poster in the Hoover Archives. The image dates from 1919, during the short life of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, and is uncharacteristically gentle for early communist iconography. Nonetheless, it had a serious purpose: inculcating the masses with revolutionary ideology, a project that Soviet Russia, with its Commissariat of Enlightenment, had already begun.

Even as the Hungarian Soviet Republic claimed to shed light, as in the poster, the regime employed terror and harsh censorship. In Soviet style, it muzzled its critics and reduced the number of newspapers from fourteen to two: a morning and evening edition of Vörös Újság (Red News). At the end, because of shortages, Red News was printed on brown packing paper.

Combat over territory and internal struggles, including a failed coup, doomed the state. On July 30, 1919, Romanian soldiers broke through Hungarian lines; Kun and most of his government fled. In the years to come, Hungary would become an ally of Nazi Germany, a satellite of the Soviet Union, the stage for another fleeting revolution (in 1956), and finally, in 1989, the parliamentary republic it is today.

Prihoda’s literacy poster suggests a limit to propaganda, a point ironically acknowledged by Lunacharsky, the Russian commissar of enlightenment (and a victim as well as perpetrator of propaganda: his name was posthumously erased from the party history during the Great Terror). “The government cannot give it [education] to them, nor the intelligent-sia, nor any force outside themselves,” he said. “Schools, books, theatres, museums, and so on can only be aids. The people themselves, consciously or unconsciously, must evolve their own culture.” As Hungary clearly did.

—Research by Yael Roberts