- History

- Military

As I write, guards are using water cannons and tear gas to turn back Middle Eastern migrants and refugees storming Hungary’s border. The media are on the side of the migrants. History sympathizes with the Hungarians.

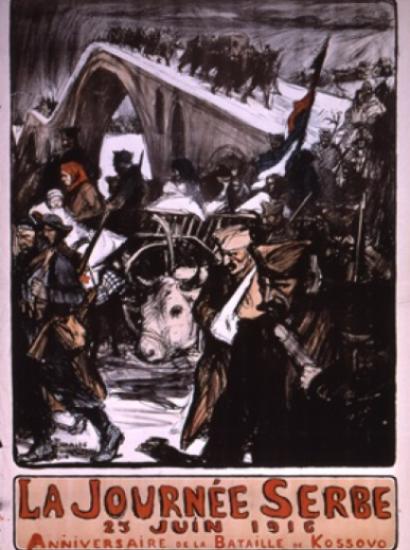

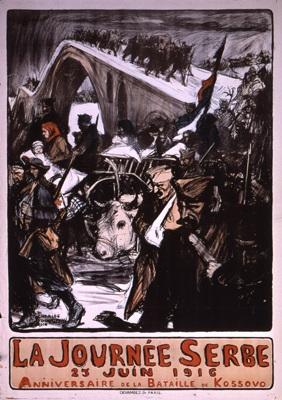

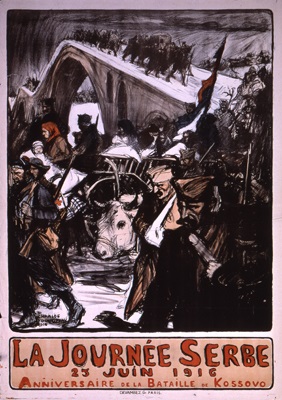

At a time when our own deep history makes headlines as we squabble about the Confederate battle flag, media coverage of the refugee crisis has ignored the historical background of Eastern Europe’s resistance to mass Muslim immigration. While some attention has been paid to the policy split over the migrants between countries, such as Germany, that need workers to support a graying population and those still facing high unemployment numbers, a deeper division exists between Western Europe and the Balkan and other East European states. Smaller nations, such as Hungary, Serbia, and Bulgaria, suffered centuries of brutal Ottoman (Muslim) rule. Others, such as Poland, spent centuries desperately resisting Ottoman and Tartar-Muslim invasions.

If our Civil War remains such a caustic force in our public mythology, what should we expect of Bulgarians who only threw off the last Ottoman chains on the eve of World War I—after suffering atrocities eclipsed only by the soon-to-follow Armenian Genocide?

In Hungary, even today, when something goes terribly wrong a common reaction is a shrug and comment, “Well, it was worse at Mohács.” That refers to a battle lost to the Ottomans in 1526, the result of which was the destruction of the Christian Kingdom of Hungary and its glittering renaissance, as well as the death of its king, Louis II. Hungary suffered Turkish occupation for almost two centuries.

Serbia cast off the Ottoman occupation in the 19th century—after five centuries of oppression that climaxed in massacres worthy of today’s Islamic State. Romania escaped the last vestiges of submission in the same century. Croatia served as a vital buffer on Europe’s southern flank, while Poland’s centuries of heroic resistance to Ottoman invasions and Tartar slave raids saved Europe.

Now the European Union wants these reborn states, most of them small and struggling, to accept a quota of Muslim migrants imposed by Brussels bureaucrats.

This looks disastrous for the EU, but the impact of a wave of culturally disconnected migrants on these still-fragile states would be worse still.

Media outlets revel in images of tear gas, water cannons, and bloodshed—as economic migrants and refugees alike play for the cameras, thrusting women and children into danger at the forefront. The ringleaders know how to excite the newsrooms of the world—which avoid reporting that these migrants are overwhelmingly young males of military age who fled their own countries rather than fight to fix them.

Syrian Christians and minorities are refugees. Most of the rest are economic migrants. When we fail to differentiate between the groups, we abet the worst factions among them.

The Hungarians are struggling—yes, clumsily—with a problem not of their making (Germany’s elephantine clumsiness triggered the latest deluge). But should we not ask, honestly, “What responsibility does Budapest have for Middle Eastern migrants and refugees? When their fellow Muslims in Saudi Arabia, the Gulf States or even Egypt accept, essentially, none? When Hungary had no role in the Middle East’s self-inflicted disasters?”

Removing history from complex strategic equations doesn’t make it easier to solve them, but only makes them harder to understand. A century after an Islamic empire was finally driven from (most of) the Balkans, we should not be surprised when few in Southeastern Europe want it back. But we’re so politically correct that, not content with lowering the Confederate battle flag on state property, we demand that East Europeans raise minarets.