Some years ago, I received a terrorist threat. If I did not apologize publicly and profusely for a column that blasted the Iranian regime, I would be killed by Friday, September 13—what an auspicious date! So I sent for the security experts, and this is what they told me: Your front and back doors are worthless; get armored ones. Order bulletproof windows. Build a safe room. Install panic buttons. Get rid of that silly chicken-wire fence and put in a steel-and-concrete one. Don’t use the driveway; try to vary your access routes (which, I think, meant sneaking home through the neighbors’ gardens). Pretty soon, we were talking six-figure costs and contemplating emigration to Iceland.

The appointed day of my demise came and went. (Real terrorists don’t write letters; they just kill you.) But the moral of this story will remain etched in my mind: when security is at stake, there is no limit to fear or fortification.

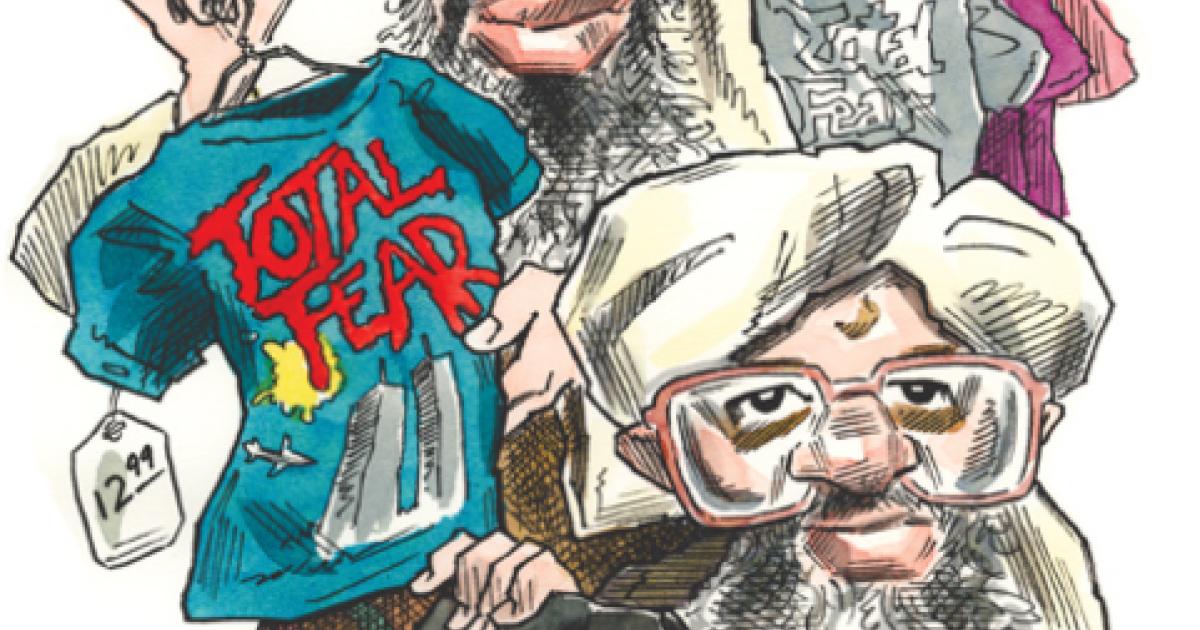

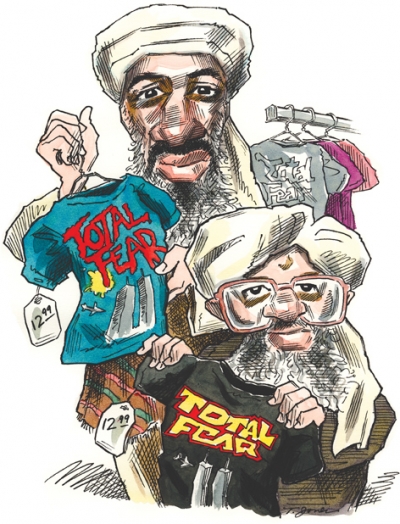

Fear, in other words, is a tax, and Al-Qaeda and its ilk have done better at extracting it from Americans than the Internal Revenue Service. Think about the extra half hour millions of airline passengers waste standing in security lines; the annual cost in lost work hours runs into the billions. Add to that the freight delays at borders, ports, and airports, the cost of checking money transfers as well as goods in transit, the wages for beefed-up security forces around the world. And that doesn’t even attempt to put a price on the compression of civil liberties or the loss of human dignity from being groped in full public view by Transportation Security Administration personnel at the airport or from having to walk barefoot through the metal detector, holding up your beltless pants. This global transaction tax represents the most significant victory of Terror International to date.

The new fear tax falls most heavily on the United States. In November 2007, the Commerce Department reported a 17 percent decline in overseas travel to the United States between September 11, 2001, and 2006. (There are no firm figures for 2007 yet, but there seems to have been an uptick.) That slump has cost the country $94 billion in lost tourist spending, nearly 200,000 jobs, and $16 billion in forgone tax revenue—and all while the dollar has kept dropping.

Why? The journal Tourism Economics gives the predictable answer: “The perception that U.S. visa and entry policies do not welcome international visitors is the largest factor in the decline of overseas travelers.” Two-thirds of survey respondents worried about being detained for hours because of a misstatement to immigration officials. And here is the ultimate irony: “More respondents were worried about U.S. immigration officials (70 percent) than about crime or terrorism (54 percent) when considering a trip to the country.”

The falloff has not been as uniform when it comes to international scholars from China, Korea, and India, who keep on coming, reports the International Institute of Education (IIE); for the 2006–07 academic year, their growth rates were between 3 and 6 percent. But the number of Western scholars coming to the United States is falling. Japan, Germany, Canada, Great Britain, Israel, Australia, and the Netherlands show declines of between 1 and 13 percent—presumably because the richer a country, the less willing its scholars are to brave the indignities they face when entering the United States.

The pattern for international students resembles that of the scholars. For 2006–07, the IIE reports the “first significant increase in total international student enrollment since 2001–02.” Again, the rise is led by the Indians, the Chinese, and the Koreans. The number of students from Japan is down, as it is for Germany. Hence the IIE’s veiled warning: “America needs to continue its proactive steps to insure that our academic doors remain wide open, and that students around the world understand that they will be warmly welcomed.” To which all Americans should say “Amen,” as these foreign students contribute about $14.5 billion annually to the U.S. economy, according to the IIE. Higher education, after all, is the fifth-largest service-sector export of the United States. And foreign talent that’s willing to stick around is one of the country’s critical natural resources.

Some U.S. officials know all this. But although the State Department protests, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) makes the rules— and will invent new verbotens by the day. Nor is there any end in sight. The demand for security, as my death threat taught me, is an obsession, spreading relentlessly, for which there is no rational counterargument. Homeland Security always asks, “What if?”—which always trumps “Why more?” A more fruitful dialogue with the Homeland Security apparat would involve this challenge: “What is the national interest?”

Which face does the United States want to show to the world? One distorted by fear and suspicion or the face that it once presented: that of a boisterous, easygoing, and welcoming society? America’s face used to be George Bailey’s genial grin in It’s a Wonderful Life, filled with the optimism and trust that can banish greed and evil; now, it’s the grim visage of Jack Bauer in 24.

This is not woolly-headed idealism but sober realism. Just imagine how the U.S. Army would have fared in liberating my home continent, Europe, if the blinkered commissars of DHS had been calling the shots in 1944. The way the last superpower chooses to bestride the world brings with it hard consequences. Does the United States open its arms or ball up its fists? Growling rarely elicits smiles, and distrust never reaps its opposite. To present a friendly face to the world is not a matter of saccharine niceness but of well-considered interests, especially for a fearsome giant like the United States. For trust breeds authority, and authority breeds influence.

What is happening to the American character? The country has certainly gone through crises of confidence before, some of them cresting in sheer hysteria—from the Alien and Sedition Acts to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s search for a commie under every State Department desk. But the worst acts from 1798 were repealed or allowed to lapse within three years, and the senator from Wisconsin was censured a few years into his red-baiting career. Alas, the USA Patriot Act and DHS have already endured longer than either earlier excess, and neither is fading.

Will the September 11 terrorist attacks change the American character in ways that John Adams’s laws and McCarthy’s mendacity could not? The answer is still no if you go to the heartland, where trusting librarians let this perfect stranger shove his memory stick into a public computer; they seemed to think that a virus scan referred to the common cold. The heartland is still Jefferson country. But when you travel through John F. Kennedy International Airport or Dulles International Airport, you notice nervousness bordering on angst, which is hardly a classic American trait. No, your neighbor will not let you leave your bag on the seat while you amble over to Starbucks.

Have the free and brave lost it? If so, Americans are not alone. Look at France, where the controls at Paris’s Charles de Gaulle Airport are just as invasive as those at Reagan Washington National Airport. Like the United States, the European Union now wants to fingerprint all foreigners who enter or leave its boundaries. The larger moral to this tale is that security is an obsession that defies natural limits. And we submit because we like it.

Al-Qaeda likes it, too. Never before have so few terrorized so many with so little.