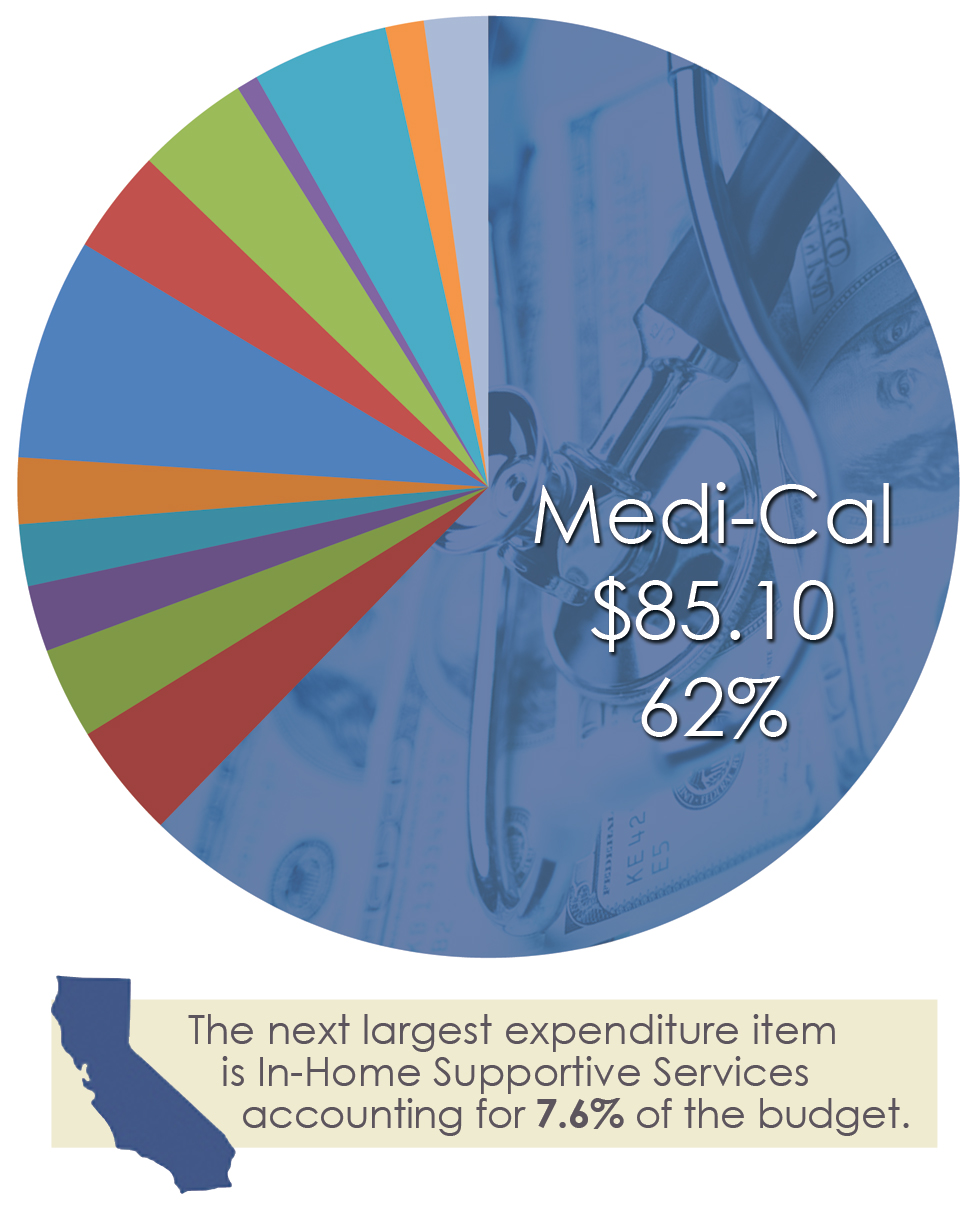

California Governor Jerry Brown’s proposed 2016-17 state budget projects that Medi-Cal enrollment – free or low-cost health coverage for children and adults with limited income and resources – will increase from 12.5 million to 13.5 million subscribers over the coming year at a total cost of $86 billion. Of that sum, $19 billion comes from the state’s General Fund, with the remainder a mix of federal matching funds, local funds, and state special funds.

Adding in Covered California subscribers means 14 to 15 million Californians – roughly three in eight Golden State residents – will be covered between the two programs. Who’s on the programs? Low income seniors, the disabled, the developmentally disabled, the severely mentally ill, children, parents and pregnant women are the basic eligibility categories. California pays a 50/50 match for most of these program-eligibles. The Affordable Care Act (i.e., Obamacare) added other uninsured low-income adults and increased the Medicaid income eligibility for parents from 100% of poverty to 138% of the poverty level (about $16,243 for an individual).

Over 80% of Medi-Cal subscribers are enrolled in managed care plans, otherwise known as HMOs. The rest are in a traditional fee for service system. Medi-Cal’s cost per eligible is low compared to other states due to three important factors: 1) low reimbursement, 2) low utilization, and 3) a younger and healthier population than the Northeast, Southern and Midwestern states.

So why the Scylla and Charybdis analogy?

First, Scylla.

Since the mid-1970’s, the percentages of Americans (and Californians in particular) with employment-based coverage have steadily declined. At the same time, health insurance premiums and costs have been growing at far faster rates than the rest of the nation’s economy.

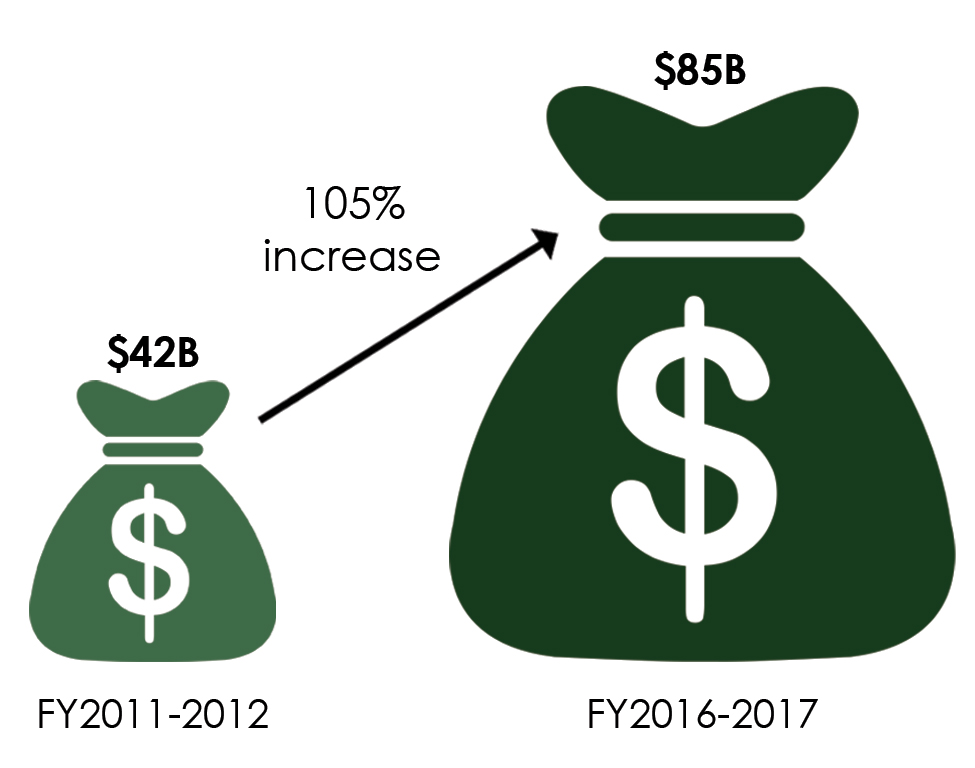

This puts enormous pressure on Medi-Cal to accommodate steadily growing numbers of subscribers who no longer have access to private coverage through their jobs and constant pressure to keep up with the supercharged growth in private sector health spending, prices, and premiums. California’s uninsured rates steadily grew to over 20% among the nation’s highest – impacting nearly 7 million California residents before the implementation of the ACA. Medi-Cal enrollment grew from about 3.5 million in 1983 to 7.8 million Californians by December 2013 at the advent of the ACA.

Now, Charybdis.

Since the late-1970’s, California voters have tied state and local finances in a series of knots. 1978’s Proposition 13 froze the growth in local property taxes, which funded public schools, public hospitals, and county and municipal governments and their programs. The following year, Proposition 4 froze the growth in state spending (the so-called “Gann Limit”) to the growth in population plus the Consumer Price Index. In the late-1980s, Proposition 98 walled off a percent of the state’s General Fund committed to public schools. And a series of tough on crime initiatives filled state prisons. Supermajority vote requirements for legislative actions on budgets and taxes and partisan gridlock in the State Capitol further drove advocates to submit a series of successful ballot initiatives to fund care of the uninsured.

Enter the ACA which expands coverage in two respects: Medicaid (Medi-Cal) expansion for the lower income uninsured and refundable tax credits through Covered California (California’s Exchange) to help with affordability of premiums. About 6 million Californians are enrolled due to the ACA and the numbers of uninsured Californians have declined by more than half. To date, the federal government has paid 100% of the new Medicaid expansion categories, but over the next three years that will slowly decline to a 90/10 match. California’s projected share will rise from about $500 million in 2016-17 growing to about $1.5 billion in 2019-2020.

County governments play a key role in financing Medi-Cal. After the passage of Prop 13 and the Gann Limit, California began a process of transferring state funding streams (principally the sales tax) and responsibilities to county governments for public health, indigent health, behavioral health, and local law enforcement; this process goes under the name of realignment. The counties in turn may and do use these and other local funds as the Medicaid match for behavioral health programs, and county hospital roles in providing care to their low income patients.

Hospitals and health plans have committed their own resources in the forms of special fund taxes and fees to support the Medi-Cal program as well. These fees and taxes must comply with the federal restrictions on provider taxes and the recent renewal of the state’s managed care organization tax of over $1 billion serves as an example of both their commitments to the Medi-Cal program and the arts of deft compromise necessary to preserve this funding.

The MCO tax was first established with the support and leadership of the local Medi-Cal managed care plans as the state struggled to maintain services and coverage during the Great Recession. The federal government determined that it was not sufficiently broad-based as required by federal law – i.e. it did not apply to all health plans, but only to those participating in the Medi-Cal program. Its continuation was a high priority for Governor Brown, as its repeal would reduce state funding by over $1 billion with a consequent loss of $1 billion in federal matching funds. The bi-partisan compromises necessary to secure its passage included offsets with the state’s Gross Premiums Tax on health plans and improvements in Medi-Cal reimbursements for care to the developmentally disabled.

While local matches and plan and provider taxes are not ideal for a host of reasons, they have been necessary components to threading the constitutional and statutory needles necessary to fund California’s Medi-Cal program. California has been one of the nation’s pioneers in ACA implementation; its ongoing and future success will depend on correctly aligning plans, providers, and three levels of government.

SCYLLA AND CHARYBDIS

Featured most prominently in Homer’s Odyssey, Scylla and Charybdis have come to represent two equally dangerous situations that must be traversed. Scylla was once a beautiful naiad who was turned into a 6-headed monster either by a jealous Amphitrite or Circe. Venturing too close to her cave resulted in her quickly snatching crew from the deck of your ship. Charybdis, either a monster who created a treacherous whirlpool or just the whirlpool itself, was located on the other side of the narrow strait from Scylla. Attempting to avoid Scylla snatching your crew could result in complete destruction by Charybdis.