- Law & Policy

Editor's note: The essay below is an excerpt from Two-Fer: Electing a President and a Supreme Court, a new book published by Hoover Press.

Every American presidential election presents different burning issues. The Vietnam War dominated three consecutive elections from 1964 to 1972. Scandals from Teapot Dome to Watergate have figured prominently in others. Recessions typically thrust economic issues to the forefront, leading one presidential campaign to adopt the famous campaign imperative, “It’s the economy, stupid!” Other issues from abortion to forced busing to education to the environment have made major appearances in national campaigns.

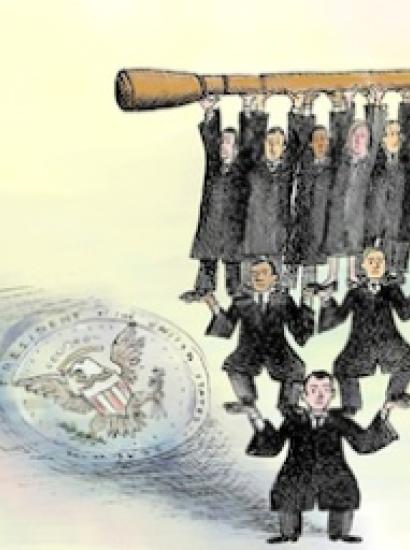

Issues come and go, and the impact of national elections in resolving those issues is often minor or fleeting. But one issue that rarely makes even a cameo appearance in national campaigns may be the most important and enduring consequence of electing a president: the party that controls the White House also controls the appointment of the federal judiciary. It is one question in which the party in power, especially over the last several decades, makes a decided difference—which in turn directly affects the lives of every single American.

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

Judges typically operate beneath the radar. Except for lawyers who practice before them, few Americans can name more than a few members of the U.S. Supreme Court, much less judges on other federal or state courts. Yet judges are powerful and important. Judges make decisions every day about religion, speech, property, business, education, civil rights, and other issues that touch all of us in direct and immediate ways. They set the rules and guide the proceedings by which accused criminals are tried and punishment is meted out. Ultimately, they determine whether our most fundamental rights are enforced or destroyed.

Think, for a moment, about who the most powerful woman in American history has been. One might nominate several candidates, but unquestionably, it is the former United States Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. She served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court for a quarter-century. Not only was she the first woman to serve on the Court, she was its only female member for most of her tenure.

But for many years, she stood far taller in influence than her male colleagues, for she typically was the swing vote in many 5-4 decisions. On matters ranging from abortion to racial preferences to school vouchers to the rights of criminal defendants to federalism, hers was often the deciding vote, and that vote usually changed the course of American history.

So courts and judges are enormously important. And yet, come election time, almost nobody thinks about them. Why? Perhaps it is because we are taught in civics class that judges are insulated from politics. Federal judges, of course, have lifetime tenure, and only can be removed through impeachment.

But, in fact, federal courts are political institutions. Judges are appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate. The appointment and confirmation of judges are enormously important powers precisely because judges are appointed for life. The Senate confirmation process in particular is important because it is the last democratic checkpoint before individuals are invested with enormous lifetime powers. Every American has a vital and direct interest in the appointment and confirmation of federal judges—which raises greatly the stakes in electing those who have the power and responsibility to appoint and confirm them.

The most powerful woman in American history is former Justice Sandra Day O'Connor.

Because of lifetime tenure, the appointment of federal judges can represent one of a president’s most important and lasting legacies, far outlasting any particular administration. President Ronald Reagan is four presidents removed from the present one, yet two of his appointees to the U.S. Supreme Court—Anthony Kennedy and Antonin Scalia—remain on the Court. Justice Scalia has been a leading conservative influence throughout his tenure, and Justice Kennedy is now the swing vote on the Court—so that Reagan continues to exert enormous ongoing influence over the nation’s course more than 30 years after he was first elected.

At the same time, the Court presently is precariously balanced. The five conservative justices usually vote together in contested cases, but the four liberal justices almost always do. The liberal justices have exhibited little moderation except on business issues. Accordingly, the shift of a single justice could tilt the Court’s balance sharply to the left—and if that happens, the liberal balance could remain that way for a generation, even if there were conservative presidents along the way.

That is because even though presidents have the opportunity to appoint Supreme Court justices, the opportunities are increasingly fleeting. Once a fairly solid conservative majority emerged on the Court in the 1990s, it survived eight years of the Bill Clinton presidency and, so far, three years of Barack Obama’s presidency. Although both Clinton and Obama named justices, in each instance, it was a liberal replacing a liberal. But, of course, the new justices were much younger than their predecessors.

The replacement of a single conservative justice by a younger liberal justice could lock a liberal majority into place for a long time. The replacement of older liberal justices with younger ones makes it much more difficult for a conservative president to influence the Court’s direction. Similarly, the replacement of a liberal justice by a conservative one would cement the Court’s conservative majority, and the replacement of older conservative justices with younger ones would fortify it.

The New Ideological Divide

Two developments have increased the importance of Supreme Court nominations. First, nominations tend to be increasingly ideological. In days gone by, it was difficult to predict a justice’s philosophy even if you knew his or her party affiliation. Some past presidents attempted to pack the Supreme Court for specific reasons. Abraham Lincoln, for instance, named justices whom he believed would support his controversial Civil War measures.

And after a bare majority of the Supreme Court repudiated some of his early New Deal ventures, Franklin Roosevelt famously proposed expanding the size of the Court so that he could shift the majority. Justice Owen Roberts’ “switch in time that saved nine,” in which he moved from New Deal opponent to supporter, helped forestall Roosevelt’s deeply unpopular threat. Still, even the justices appointed for particular purposes by those presidents were unpredictable and divided on other issues.

For instance, the Slaughter-House Cases in 1873 presented a 5-4 Supreme Court split that was extremely rare in that era. The decision involved the privileges or immunities clause of the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment. A group of butchers challenged a bribery-procured Louisiana slaughterhouse monopoly on the grounds that it violated their freedom of enterprise, whose protection was a principal goal of the Fourteenth Amendment’s framers. A majority of the court, over three passionate dissenting opinions, ruled against the butchers, thereby obliterating the privileges or immunities clause and judicial protection for economic liberty.

We are taught that judges are insulated from politics. But the courts are political.

In Slaughter-House, the seven Republican justices divided four to three and the Democrats divided one apiece. More to the point, Lincoln’s five appointees were split, with two joining the majority and three dissenting. It would be extremely unusual today to see that type of split in a contentious case among justices appointed by the same president.

Similarly, in the 1944 decision in Korematsu v. United States, the infamous decision in which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the internment of Japanese citizens, five justices appointed to the Court by Franklin Roosevelt (Hugo Black, Stanley Reed, William Douglas, Wiley Rutledge, and Felix Frankfurter) voted with the majority, while two others (Frank Murphy and Robert Jackson) dissented. (The two remaining justices appointed by Republican presidents split their votes.) While Roosevelt’s appointees tended to march in lockstep on New Deal issues, they were deeply divided over civil liberties.

Richard Nixon, who was elected in part due to popular reaction against the excesses of the Supreme Court under the leadership of Chief Justice Earl Warren, may have been the first president to make a concerted effort to name justices with broad consistent judicial philosophies, specifically “strict constructionism.” He failed.

Nowhere was that more apparent than in Roe v. Wade, the decision upholding the 1973 right to abortion. By that time, Nixon had appointed four of the nine Supreme Court justices. Had all of them voted together, they could have formed a majority against the right to abortion. But three of the four (Harry Blackmun, Warren Burger, and Lewis Powell) voted in favor of the abortion right, while only one Nixon appointee, William Rehnquist, voted against. The two Eisenhower holdovers, William Brennan and Potter Stewart, also voted in the majority; along with Thurgood Marshall, who was named to the Court by President Lyndon Johnson. The only justice joining Rehnquist in dissent was Byron White, a Democrat who was nominated to the Court by John F. Kennedy.

Throughout history, then, justices in landmark cases frequently departed from the philosophies of the presidents who appointed them, and a partisan divide on the Supreme Court was the rule rather than the exception.

That changed, starting with the election of President Reagan, who was far more systematic and successful than his predecessors in appointing judges and justices who shared his judicial philosophy. Since Reagan, Republican presidents have tended consistently to nominate conservative justices and judges, and Democrats have nominated liberal justices and judges with similar determination and success. In terms of the Supreme Court, the principal exception was Justice David Souter, nominated by the first President Bush, who was a consistently liberal vote.

Even Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy, who were appointed by Reagan and have occupied the Court’s ideological center, have moved constitutional jurisprudence in a conservative direction. Democratic presidents since Reagan, though so far having had fewer appointments, have a perfect record in appointing justices with liberal philosophies.

The ideological homogeniety of Supreme Court justices reflecting the philosophy of the presidents who appointed them is illustrated by numerous recent decisions. In both McDonald v. Chicago, which applied the Second Amendment to the states to strike down Chicago’s handgun ban, and Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission, in which the Court held that corporations have a protected First Amendment right to political speech, the Court was split 5-4 along now-familiar liberal and conservative lines. Among the liberal dissenters, only Justice John Paul Stevens was appointed by a Republican president. With his replacement by Justice Elena Kagan, who was appointed by President Barack Obama in 2010, there is perfect homogenieity within the Court’s liberal and conservative wings, in that all five conservative justices were appointed by Republican presidents and all four liberals were appointed by Democrats.

That is not to say that the justices are partisan. Quite to the contrary, there are few cases in which the justices’ political views appear to influence their decisions. Rather, each of the justices have sincere, deeply held views on legal issues. Nor is that divide, much as some conservatives might simplistically wish to describe it, as one between judicial activism versus judicial restraint. Indeed, in recent years, some liberals have criticized conservative justices for being too activist, in the sense of striking down (in their view) too many laws.

The divide between the Court’s liberals and conservatives—and to some extent, the lesser divide within the two camps—emanates mainly from different philosophies about constitutional interpretation. The conservatives tend to advocate “original intent”—that is, an attempt to determine the original meaning of constitutional provisions and to apply them to contemporary circumstances.

Even within that philosophy, there are variations; for instance, placing different weight on constitutional text, the views of the framers, legislative history, and tradition. Some justices adhere strongly to the principle of stare decisis—that is, deference to past precedents—while others do not. Some justices use foreign law to help interpret American law, while others disdain that practice. Among current justices, the leading advocate of judicial restraint—or as he calls it, “judicial modesty”—is not a conservative but a liberal, Justice Breyer, who believes that courts should defer to manifestations of “active democracy.”

Still, despite some aberrations, the 5-4 conservative/liberal split tends to hold on nearly all deeply contentious issues, ranging from racial preferences to religion to property rights. Much attention is focused on the cohesiveness of the Court’s conservative majority—or at least the “core four” of Roberts, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito—in fact, the four liberal justices (Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Kagan) are even more cohesive.

Lifetime tenure is more meaningful today than when the Constitution was ratified.

Every year the New York Times catalogues the votes of the justices for the prior Court Term. In the nine cases that the Times considered most important during the Court’s 2010-11 Term, the four core conservatives voted in unison in six—while the liberals voted together in eight of nine. Justice Thomas often is derided by liberals for voting so frequently with Justice Scalia—and indeed, he did so in 89 percent of the cases in 2010-11. But each pairing among the liberal justices voted together between 85-94 percent of the time, exhibiting tremendous cohesion.

The deep philosophical divide among Supreme Court justices on major issues underscores a very significant development in modern politics: the president’s partisan affiliation makes a tremendous—indeed defining—difference in Supreme Court nominations. From a conservative or libertarian perspective, the worst Republican will be better than the best Democrat in terms of choosing judges; and the converse is equally true for liberals.

The Rise of the Federalist Society

Why are judicial nominations more ideologically driven than ever before? And why have recent presidents proved more successful than their predecessors in appointing judges who reflect their judicial philosophies?

One explanation is the emergence of an organization that has done more to influence to selection of judges during Republican administrations than any other. The Federalist Society for Law and Policy Studies was formed in 1982 by law students at Harvard, Yale, and the University of Chicago, with support from former Attorney General Edwin Meese, former Solicitor General Theodore Olson, and former Judge Robert Bork. The Federalist Society’s mission was to counter the liberal influence in law schools, legal academia, and the practice of law. To say that it has succeeded in greatly advancing that mission over the past 30 years is a tremendous understatement.

From humble beginnings, the Federalist Society now has chapters at more than 200 law schools, with 10,000 law student members and 30,000 lawyer members. The group coheres around the principle that the proper role of judges is to determine what the law is, not what it should be. Apart from that core shared belief, a great deal of philosophical diversity exists within its predominantly conservative and libertarian ranks. For instance, Bork believes strongly that courts should rarely if ever decide issues of public policy, while University of Chicago law professor Richard Epstein would have courts invalidate much state and federal legislation enacted over the past century—yet both are active in the Federalist Society.

What the Federalist Society lacks in doctrinal dogma, it more than makes up for in robust debate. Nearly all of its activities consist of balanced debates on issues of legal philosophy. So important is that role that I have frequently heard liberal law school deans remark that if it were not for the Federalist Society, there would be no debate at all in their law schools.

By fostering such debate, the Federalist Society has given rise to legal academics and judges who have spent a great deal of time thinking about and developing judicial philosophies. The student members of the Federalist Society often work as research assistants and law clerks to those professors and judges, and frequently go on to prestigious posts in legal academia, law practice, and the judiciary. All of that activity makes it easier for Republican presidents to nominate judges with well-developed philosophies who are unlikely to disappoint them after they join the bench.

The foment on the right has triggered a reaction on the left, including the creation of the American Constitution Society, which seeks to counter the Federalist Society’s influence in law schools. (Happily, the two organizations often co-sponsor debates, ensuring that the forums are well-balanced and of high quality). Both sides, not to make a pun, have a deep bench from which to draw appointments to the federal judiciary.

Augmenting the increased supply of potential judges whose philosophies of law are fairly well-known in advance is the recognition among both Republican and Democratic presidents that judicial nominees are very important to their respective political bases. Whatever their perceived apostasies on public policy issues, presidents can mollify their core constituencies when they appoint judges to their liking. Or, at the very least, they have learned not to name judges who alienate their core constituencies.

A case in point was President George W. Bush’s nomination of White House counsel Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court. Though Miers may have been conservative, her views were not sufficiently well-known, nor her philosophical bonafides established enough, to satisfy movement conservatives. The resulting tempest brought down the nomination, and resulted in the appointment of Justice Samuel Alito, Jr., a superb choice from a conservative perspective.

Human Longevity and Lifetime Tenure

The second development that has increased the importance of judicial nominations is human longevity. It is often remarked that if people want to live a long life, they should become Supreme Court justices; if they want to live a short life, they should become retired Supreme Court justices. The few individuals who serve on the nation’s highest court typically stay until a very advanced age. Justice Thurgood Marshall once noted, when asked about the possibility of retirement, that he had a lifetime appointment and intended to serve every day of it.

Lifetime tenure is far more meaningful than it was when the Constitution was ratified. Life expectancy today is roughly double what it was in the late 1700s. Naming someone to a lifetime post wasn’t that big of a deal when, as in the late eighteenth century, the average age of the nominees was 50 and average life expectancy was in the 30s. It is a much bigger deal in the twenty-first century, in which the average age at appointment to the Supreme Court is about 52 and average life expectancy is 76. To take the most recent example, when Justice Elena Kagan was nominated at age 50, her total life expectancy was 85 years. Hence, assuming good health and a desire to serve out her term, Justice Kagan’s expected tenure would be 35 years—spanning nearly nine presidential terms. That is a serious presidential legacy.

The average age at which justices are nominated to the Supreme Court has not changed significantly since our nation’s early days. In the first 25 years following the Constitution, the average age of Supreme Court nominees was 50; today it is about 52. The average age of nominees increased to nearly 59 in the latter part of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century.

A president can influence policy for decades by nominating the right judges.

But modern presidents seem to be catching on to the prospect of a lasting legacy: since 1972, only one of the dozen confirmed justices had a “six” in the first digit of her age (Ruth Bader Ginsburg, nominated at age 60). The others were in their 50s, except for Clarence Thomas, who brought down the average by having been named to the Court at age 43. If he serves to the same age as his predecessor, Thurgood Marshall (age 83), he will be on the Court for 40 years—and despite having been appointed by the elder President Bush in 1991, he is only midway through that tenure. If he serves that long, he will eclipse the record tenure of Justice William Douglas, who served on the Court for 36 years.

Hence, lifetime tenure for Supreme Court justices has become an enormous and ever-growing prize for presidents—and both sides of the ideological divide are keenly aware of the stakes.

Bitter Confirmation Battles

Those stakes have translated into bitter Supreme Court confirmation battles—but only when control of the Court is at issue. The two most recent nominations that affected the Court’s balance led to vicious confirmation battles.

The first was the nomination of Robert Bork to succeed Justice Lewis Powell, Jr., who occupied the center of the Court toward the end of his tenure. Bork would have fortified the conservatives on the Court and moved it solidly to the right. Led by Sen. Edward Kennedy, Democrats strongly opposed the nomination, in some instances exaggerating Bork’s views. Bork defended himself gamely but to no avail—his nomination was defeated. President Reagan then nominated Judge Douglas Ginsburg, a libertarian whose nomination was withdrawn because as a law professor, Ginsburg had smoked marijuana with students. Having failed twice, Reagan turned to Judge Anthony Kennedy, a noncontroversial conservative.

The fall-out from the Bork nomination led to the 1990 nomination of Judge David Souter, who had served as a justice on the New Hampshire Supreme Court and a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit without a clear philosophical record. Democrats suspected that Souter was a “stealth” nominee—and President Bush no doubt intended him to be one—but Souter turned out to be a solid liberal vote on the Supreme Court. An important lesson was learned, and subsequent presidents have taken great pains—with great success—to satisfy themselves that their Supreme Court nominees will not disappoint them.

Following Souter came the political cataclysm over the nomination of Judge Clarence Thomas, which replaced the Court’s most liberal justice (Thurgood Marshall) with arguably its most conservative. Liberals were not about to let that happen without a fight, in which no means was beyond consideration to achieve the desired ends. Opponents searched Thomas’ trash cans and scoured the country for anyone who could damage the nominee. In the end, Thomas prevailed by a 52-48 vote in the Senate. But the battle against the nomination marked a new low in political discourse, which we are all too likely to see again the next time a nominee might alter the present balance on the Supreme Court.

Although Supreme Court nominations since Thomas have been relatively quiet affairs because they have not altered the Court’s ideological balance, there have been numerous confirmation battles over lower-court nominations, especially where confirmation might help credential the nominees for future vacancies on the U.S. Supreme Court. In 2001, President George W. Bush nominated an exceptionally bright conservative, Miguel Estrada, to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit—a court from which many Supreme Court justices are nominated. Estrada emigrated to the United States from Honduras, and could have been the first Hispanic justice in a future Republican administration. Democrats successfully filibustered the nomination and Estrada never made it to the Court.

***

Given the huge and central importance of federal judicial nominations, it is striking that the issue rarely comes up in presidential contests. Certainly since the early days of the New Deal, there has not been a Supreme Court whose philosophical compass is as opposed to that of the presidential administration’s as the current Court. And yet the Court’s 5-4 conservative majority hangs in precarious balance. Four of the current justices—two conservatives (Scalia and Kennedy) and two liberals (Ginsburg and Breyer)—are in their 70s. The odds are strong that one of our next presidents will have the first opportunity in over two decades to alter the Court’s ideological balance, either fortifying the conservative majority or tilting it to a liberal majority. Either way, it will determine, in large measure, the future course of our nation.

Even if it is usually an invisible issue, the bottom line is that nominating judges is the grand prize in presidential elections. It also provides perhaps the most important reason to vote either for a Republican or Democrat for president. A Republican president may disappoint his or her base by creating a massive new entitlement program or declaring that it is necessary to destroy capitalism in order to save it. A Democratic president may disappoint the base by engaging in foreign wars or declaring that some businesses are too big to fail. But recent experience suggests that they will rarely, if ever, disappoint their respective core constituencies on judicial nominations. And those nominations will have tangible, enduring consequences for generations to come.