From the rhetoric of President Bush to his dispatch of Patriot air-defense systems and a second carrier battle group to the Persian Gulf, there are growing signs that the Bush administration is showing itself willing to solve the Iranian nuclear crisis with a preemptive military attack. The already tense U.S.-Iran relationship is now a tinderbox.

Secretary of Defense Robert Gates was correct when he stated recently that Iran is “acting in a very negative way” in the Middle East. The Islamic Republic trains and supports Hezbollah and Hamas; it provides aid and explosives to Iraqi Shiite militias who attack American soldiers; and, most alarming, it seems determined to develop a nuclear bomb. This panics moderate Arab states and poses an existential threat to Israel. The ruling mullahs in Tehran terrorize their own citizens, especially pro-democracy groups.

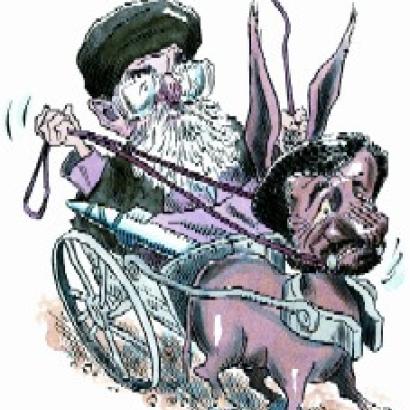

| President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is neither particularly beloved nor preeminently powerful. He has enemies, and, in the constant power struggle in Iran, he is slipping. |

Bombing Iran, however, would not resolve any of these dangers—it would exacerbate them. But where military strikes would fail, containment and comprehensive negotiations would succeed.

Contrary to conventional accounts, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is neither the most powerful official in Iran nor beloved by the Iranian people. The authoritarian regime is not united behind Ahmadinejad and his policies but divided and uncertain about who will prevail. The real kingpin in Iran is supreme leader Ayatollah Khamenei, whose failing health has launched a succession struggle. On one side of this fight are Ahmadinejad, a cabal of leaders from the Revolutionary Guards, and the Basij (the militia-gangs that terrorize the regime’s opponents). On the other side is a loose coalition united by disdain for Ahmadinejad’s gross economic mismanagement and reckless hubris. This includes Iran’s bulging generation of young people, along with businessmen, technocrats, reformists, allies of former president Hashemi Rafsanjani, and even the conservative Motalefe Party.

After a year of rising stardom, Ahmadinejad is starting to lose this power struggle. He has not delivered on his campaign pledges to fight corruption or improve the lot of the working classes and the poor. In recent elections for local councils and for the powerful 80-member Council of Experts (entrusted with the task of choosing the next spiritual leader), Ahmadinejad and his allies suffered humiliating defeats.

To reverse his waning popular support, Ahmadinejad has tried to change the subject from his domestic failures to his foreign adventures. He knows there is only one thing that could bring the people back to him—a U.S. military attack on Iran. His repulsive remarks about Israel and his nuclear bravado aim precisely to provoke such an attack, which would create the crisis conditions necessary for his faction to seize full power.

Even as Iran’s reactionaries pine for war, some of Iran’s more moderate leaders have written the Saudi government, asking it to help reduce tensions between the United States and Iran. A military confrontation with U.S. forces would silence these moderates.

In fact, Iran’s democratic opposition warns that a U.S. military strike would strengthen the regime hard-liners and weaken the opposition’s already limited ability to operate. If Ahmadinejad welcomes war with America and Iran’s dissidents fear it, shouldn’t the Bush administration think twice about the unintended consequences of military action?

If Ahmadinejad does consolidate power, Iran would act in an even more negative way, and with soaring support throughout much of the Muslim world, for an American attack would elevate him to hero status.

This would only fan his faction’s ambitions to establish Iranian hegemony in the Middle East. Its support for terrorist organizations would increase. Terrorism, polarization, and sectarian violence would intensify in Iraq, Lebanon, the Palestinian territories, and Afghanistan, and could begin to engulf Bahrain and even the Shiite region of Saudi Arabia—where most of the country’s oil is.

A sustained U.S. bombing campaign would disrupt Iran’s nuclear weapons programs. But the newly consolidated hard-line regime in Tehran would be even more emboldened to acquire such weapons. A preemptive attack, which would lack international legitimacy, would also prompt Iran to withdraw entirely from the nuclear nonproliferation regime, as some of Ahmadinejad’s allies have already threatened, while inducing the crucial international fence-sitters—Russia and China—to back Iran without hesitation.

There is an alternative. Rather than throw the reactionaries in Tehran a political lifeline in the form of war, the United States should pursue a more subtle approach: contain Iranian agents in the region, but offer to negotiate unconditionally with Iran on all the outstanding issues. Comprehensive negotiations could offer the powerful inducements—such as lifting the economic embargo and promoting a significant influx of foreign investment and thus jobs—necessary to persuade Iran to halt nuclear enrichment. And if the hard-liners reject the offer, they would have to contend with an angry Ira-nian public. Such internal strife would be far preferable to an Islamic Republic united against the attacking forces of the “Great Satan.”