- Health Care

Recently, a distinguished list of academics signed an open letter to President Barack Obama, Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Matthews Burwell, Attorney General Eric Holder, and the leaders of Congress. The letter implored the administration to take prompt and effective steps to end the shortage of organs now available for transplants, especially kidneys. Its signatories announced: “We call for the swift initiation of evidence-based research on ways to offer benefits to organ donors in order to expand the availability of transplants.“

I chose not to sign that letter. It was not because I disagreed with its unhappy diagnosis that the chronic shortage of organs available for transplants, especially kidneys, is inexcusable; on that point, the letter was spot on. Rather, I refused to sign because I believe that the letter’s call to action was hopelessly slow in the face of an unending cascade of unnecessary deaths. If heeded, its call will be the latest in a long series of well-intentioned failed attempts to end the government scourge created by the current ban on kidney sales. This ban was implemented by the National Organ Transplantation Act (“NOTA”) of 1984, sponsored by Senator Orrin Hatch and then-Representative Al Gore. NOTA’s central provision makes it illegal to “acquire, receive, or otherwise transfer” an organ to another person for “valuable consideration,” which with minor exceptions blocks both cash and in-kind payments.

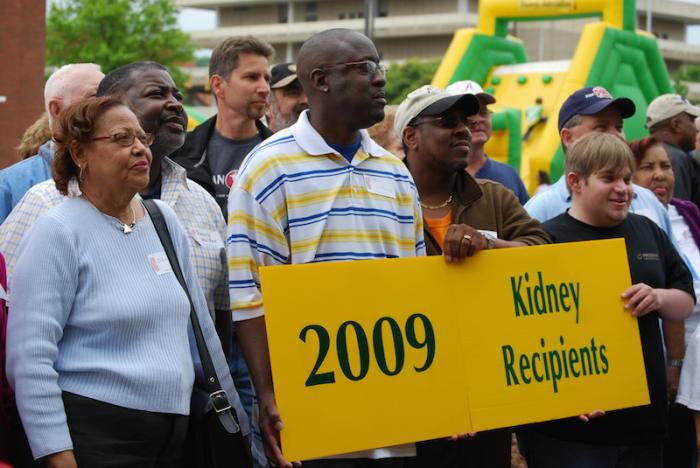

To solve the problem of organ shortages, we must begin by repealing NOTA and implementing a free market for organs. The area in which that voluntary market would work best is for kidneys, both live and cadaveric. Kidneys are the most desperately sought organ. Of the close to 125,000 people now waiting on the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, (OPTN) transplant list, more than 100,000 are waiting for kidneys, and the number is rising daily. Relative to transplants of pancreas, livers, hearts, lungs, and intestines, kidney transfers are the easiest to execute, with the greatest benefits to the recipients and the transferors alike.

The open letter reports that we are in a losing battle with kidney shortages. On the supply side, the number of live donations is now down to about 5,700 per year from 6,000 per year some five years ago. Most of those transfers come from family members, where the matches may be less than ideal, and the health of the donor less than perfect. Also on the supply side, the number of accidental deaths of young individuals is down, which cuts off, for the best of reasons, the most desirable source of cadaveric kidneys. On the demand side, better healthcare now allows individuals who suffer from diabetes and kidney disease to live long enough so that they will actually need dialysis or other treatment.

The ability to get organ donations from strangers is very small even though the net benefits are enormous. The mortality risk to the donor is in the order of 3 parts in 10,000. The extra life to the recipient of a live kidney is in the order of 15 to 20 years. (That figure is far greater than the gains from a cadaveric kidney, whose condition is likely to be degraded at the time of death, and to deteriorate thereafter in the interval needed to complete transplantation, if consent can be obtained in time from grieving relatives.) The gains to recipients of a live transaction, if monetized, could easily exceed one, even two, million dollars, at a total cost that is below $100,000 per donor, which includes personal discomfort, loss of work time, and family dislocations. But altruism does not work well when donors have to incur uncompensated losses of that size. Unfortunately, the huge potential for gains from trade is blocked by the firm NOTA prohibition against organ sales.

The open letter does not refer to those gains from trade. It in fact criticizes them. “To ensure equality,” it reads, “private transactions between individuals should remain prohibited.” The letter then seeks to accomplish the impossible by endorsing a centralized approach administered by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). This nonprofit organization was founded in 1984, when the risks of kidney transplants were greater and the waiting lists far shorter than the 4.3 years of today. This is up from 2.8 years only five years ago. If UNOS remains in charge, the waiting times will continue to grow.

On the positive side, the letter proposes a set of possible healthcare experiments that might involve the provision of in-kind compensation to potential donors that could cover life-long health and disability insurance and funereal benefits. These could, in principle, be supplemented by “a pension contribution, tax credit, or charitable contribution.” Unfortunately, the letter frets so much about the downsides of improvident kidney transfers that it accepts a set of procedural limitations that doom the experiment. New experimental programs, doubtless subject to extensive internal oversight, have to meet as-yet unspecified standards on informed consent, psychological tests, and of course long wait periods before the donation can take place.

The simplest objection to this program is that it is too little and too late to dent the shortage. Any government experiment will take years first to debate and then to perform. Thereafter further delays will be incurred in trying to make sense of fragmentary data. Any pilot programs will prove yet again that justice delayed is justice denied, especially for the thousands of individuals who die in the interim.

It’s important to realize that any short-term experimental approach cuts out some indispensable benefits that only open markets can supply. The basic logic of a market is that it allows people to match up with others in order to secure gains from trade, which, as noted above, are huge for potential live kidney transplants. But kidney markets are difficult to organize because real gaps in information plague both sides of the market. After all, kidney transplants take place only once for any live kidney donor, and rarely more than twice for any kidney recipient. In one sense, these markets are even more difficult to crack than real estate markets, which exhibit a similar pattern of low-frequency and high-value transactions.

To navigate these markets, it is therefore critically necessary for third party intermediates to add their reputational bond and transactional skills to assure, as brokers, both buyers and sellers (no more donors, as it were) that the transaction will go as scheduled. And, no, there is no need for the government to supply these intermediates. The market forces that generate brokers for real estate could work here, where customers on both sides of the market enjoy full legal protections against bad performance, misrepresentation, and mistake.

Even if the signatories of the letter had urged government officials to allow for ordinary market transactions to take place for a year, the experiment would thunderously fail. The temporal limitation on the market would make it uneconomic for any third person to invest the lump-sum capital needed to set up the brokerage operation in the first place. The failures that would ensue would be interpreted as convincing evidence that markets necessarily fail, when the better explanation is that they offer proof-positive that poor experimental designs cannot replicate actual market conditions.

So why not take the plunge? One standard objection is that individuals could be “coerced” into selling their organs. But this argument is exactly backwards. To find coercion, look no further than the family situation where one member is an organ match for a sibling or a child, but has serious qualms about taking the risk in question. Now money or in-kind benefits cannot be offered to offset that risk. So the full array of nonstop family pressures can be imposed in order to get the reluctant relative to change his or her mind. But in an open market, the potential of thousands of unrelated donors makes it both impossible and unnecessary to bring subtle pressures to bear on these strangers. Coercion is not an inherent consequence of voluntary exchanges. Rather, it is a far greater risk when only uncompensated transfers can be allowed.

A second objection is that the voluntary market will discriminate against the poor who do not have the means to pay. To this point, two responses are in order. First, right now rich people can influence the UNOS allocation process to work their way up the queue. Richer people have more contacts and more resources to spend on getting themselves on, if necessary, multiple queues. Worse still, there are all sorts of opportunities to divert cadaveric organs to favored recipients, as major transplant centers can keep harvested organs for their own patients by claiming that their condition renders them unfit to be transferred elsewhere. No system that allocates huge benefits for zero or below market price will be immune from influence, whether we are talking about rent-controlled units in Manhattan or unassigned kidney organs, whose donor, often young and poor, receives not one cent from the successful transfer.

Second, money does not have to be an obstacle to getting a kidney transplant. If we redirect some subsidy funds away from dialysis treatments, people who cannot afford to pay for an organ could still have the opportunity to receive a transplant. As the open letter notes, right now 7 percent of the Medicare budget goes to dialysis and organ transplantations. Figures for 2010 reported $32.9 billion going to End State Renal Disease, and the number is surely higher today. That money is misspent. As the letter notes “each transplant saves the health care system more than $100,000 compared to dialysis.” That money should be given to the recipients, and they should be able to keep the change when they buy an organ. The numbers cancel out even on the wholly unrealistic assumption that a kidney transplant, like dialysis, lasts only for one year. But write the total cost of the kidney off over several years, and the government can easily double the $100,000 figure, save money, and induce a ready supply of donors, who will accept lower prices as transplant techniques develop and the matching system improves.

Open markets could solve the organ shortage problem. On the donor side, it will induce high-quality sellers, because no one wants to buy a hepatic or diseased kidney. On the recipient side, the cash supplements could go a long way to increase organ access to indigent and minority patients, who are currently ill-served by the system. The big losers in this program will be the purveyors of dialysis services. But, the winner will be the large number of stricken people who, liberated from these machines, can live better and richer lives.