Though hard to believe, and painful to contemplate, Americans face another round of elections in barely a year’s time. If the last few elections are any indication, we will hear a lot about job creation again in 2014. Unemployment remains higher than most people are willing to accept, and there are millions of Americans who have dropped out of the search for work, making the not-very-good official numbers appear better than they really are. Jobs are certain to be near the top of every candidate’s list of priorities.

Unfortunately, prospects for new and long-term employment opportunities for the currently unemployed and for those newly entering the job market are not likely to improve, at least not as a result of government policy, if the political debate remains focused on job creation per se. What we need are government policies that allow for and facilitate a thriving economy. The jobs will follow.

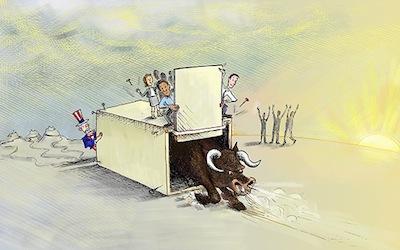

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

The job creation rhetoric of the last two elections went like this. Conservatives insisted that jobs are created by the private sector, not the government. Mitt Romney ran for president claiming experience as a job creator. Many other Republican candidates with business backgrounds made the same claim. Meanwhile, liberals urged that government must play a central role in job creation, both through stimulus of the private economy and direct hiring by government. Democrats even provided remarkably precise accounting of the number of jobs their stimulus spending had created, while declaring that capitalists like Romney had actually been job destroyers.

While it is silly to suggest that we might calculate, with laser-like precision, how many private sector jobs result from general government spending, it is certainly true that direct government funding of private or public sector jobs creates employment that did not previously exist. But it is also true that such government created jobs will persist only so long as the government continues to fund them, which means that money that might otherwise be invested in private enterprise must be diverted (as taxes) to government coffers. While these taxpayer funded jobs last, however, it cannot be denied that they take people off the unemployment rolls.

Liberals, particularly those enamored of the once moribund Keynesian economic theory, will disagree and claim that money spent on government jobs will somehow stimulate increased private employment. Furthermore, they will contend that many jobs created in response to government subsidies and tax breaks will persist if they are with innovative businesses that cannot get private financing but will prosper and provide long-term employment once they get off the ground. The evidence in support of this theory is mixed—note the many “green” energy companies that have failed even with generous government subsidies—but where such businesses do succeed after subsidies end, it is fair to ask whether such tipping of the competitive scales costs at least as many jobs among disfavored businesses as it encourages among the favored.

Whatever the conclusion with respect to net, long-term employment resulting from government subsidies, it would seem that Republicans are wrong to insist that government does not create jobs. Government does create jobs by the simple expedient of employing people or paying private enterprises to employ people. Whether the net result is more jobs is a different question.

What about the Republican claim that the private sector is the true job creator? Wrong again, at least if the claim is that the private sector creates jobs for the sake of creating jobs. Only government and some private charities create jobs for the sake of creating jobs. Any private sector employer whose mission is jobs creation will not long survive in the marketplace. Indeed, success in private business often turns on finding ways to cut jobs. Only with direct government subsidies tied to job creation will the private sector even consider creating jobs for the sake of creating jobs.

It might be objected that political candidates are not really saying that the private sector can create jobs at will. But the reality is that the political rhetoric of job creation distracts elected policymakers from what needs to be done if we are to have an economy that provides ongoing opportunities for everyone seeking employment.

Although employees might view their employer as a job creator, the reality is that jobs in the private sector are a fortuitous byproduct of successful business pursuits that have nothing to do with job creation. Indeed, from the perspective of employers, jobs are a necessary cost of the pursuit of those other objectives, costs that will continue to be incurred only so long as the business is successful. What are those other objectives? They are the provision of products and services that people want and are willing to purchase, the creation and delivery of these products and services at competitive prices and quality, and, at the end of the day, the generation of revenues in excess of expenses. A business plan that calls for job creation without explaining how the business will eventually be profitable while paying for those jobs will not attract financing by any intelligent investor.

The point is not that jobs are unimportant or that successful businesses do not invest in their employees and seek to provide a good work environment. Rather, the point is that job creation is never the mission of private enterprise because there is no market for job creation. Of course there is a market for jobs, but no one, aside from government and some charitable organizations, is willing to pay for the mere creation of jobs. That’s because there is no economic return on jobs unless those employed are producing products or services that yield sufficient revenue to cover all expenses including compensation for employees.

Perhaps this all seems obvious. It should be. But if it is, why do Republicans insist that government can look to the private sector for job creation? Why do Republican candidates like Mitt Romney claim that because their businesses provided employment, they know how to get government to get businesses to create even more jobs? If they were successful in business, it is not because they set out to, or even know how to, create jobs. Rather whatever success they experienced resulted from creating, producing, and supplying products and services consumers were willing to purchase. Employees are just an expense, along with capital investment, debt service, regulatory compliance, and a host of other costs, all of which combined must be less than revenues from sales of products and services.

When candidates for public office run on a platform of job creation, we might accept it as political rhetoric and assume that they understand that new jobs come with new and expanding businesses in a growing economy. But politicians often come to believe their own rhetoric, and voters look to those elected to deliver on their promises. If the promise is that government will create jobs, we should expect policies providing for direct government employment or taxpayer funded jobs in the private sector—and that is what we have gotten. But what policy initiatives should we expect form those whose rhetoric is that the private sector creates jobs?

We know from experience that Republicans are more than happy to support government subsidies and tax breaks for private businesses, especially if those businesses are in the politician’s district. When such subsidies and tax breaks are contingent on the creation of new jobs, politicians can point to a direct link between the policy and the jobs, assuming we can actually account for jobs created because of a subsidy (do “jobs saved” count?). And even absent such a contingency, politicians will not hesitate to claim that net new jobs from the time a subsidy or tax break took effect are the consequence of that government policy. But is job creation by subsidy and tax break really any better than job creation by direct government employment? In both cases, new jobs generally come at the expense of, not as a consequence of, a thriving economy.

The point is that the rhetoric of private sector job creation leads to policy prescriptions that actually encourage businesses to create jobs for the sake of creating jobs. But that is not what we should be doing if we aspire to prosperity and a thriving private sector that will employ lots of people in long-term jobs while paying taxes to support important public services.

Rather than a rhetoric that embraces affirmative government actions to stimulate private job creation for its own sake, Republicans (and Democrats) should advocate for the free market, for appropriate government regulation of that market, and for private creation of wealth that can underwrite future wealth generating enterprises and support (through taxes) the government’s role as supplier of public goods and redistributor of wealth to those truly in need. In sum, they should promote public policies that create and maintain a good business climate.

In 2014, it would be good to hear candidates of both parties acknowledging that all of the good things government does depend on funding from taxes paid by successful businesses and those who work for those businesses. Government can employ people and those employees can provide valuable public services, but only if those in the private sector generate enough revenue net of taxes to meet their own expenses including a reasonable return on investment. If those who aspire to make public policy at all levels of government really want to shorten unemployment lines and encourage renewed productivity by those who have dropped out in frustration, their campaign promises should focus on policies that will encourage private initiative, investment, and growth. The jobs will come.