- Contemporary

- World

- History

His name is little known in the West but what this 78-year-old Russian diplomat-intellectual has done over the last 13 years merits the applause of all of us who hope for the full democratization of Russia.

He is Alexander Yakovlev, onetime trusted adviser to Mikhail Gorbachev, when Russia was still the Soviet Union. For the past 13 years he has been director of the Russian Presidential Commission on the Rehabilitation of Prisoners, tasked to investigate the crimes of the Stalin regime. His work began in 1989 under the direction of the Gorbachev-controlled Politburo and continued after 1991 into the Boris Yeltsin era.

During that time, the commission has posthumously rehabilitated 4.5 million people, all of them victims of Josef Stalin and even his successors. In other words, they were victims of frame-ups by Stalin’s secret police and the prevalent system of “telephone justice”; that is, a phone call would come to the judges telling them what verdict to pronounce. Some 400,000 cases remain, and the rehabilitation will probably be completed soon.

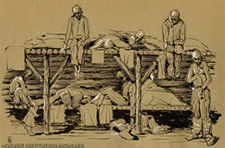

Actually, Mr. Yakovlev estimates, at least 20 million people if not more suffered political persecution during the Soviet era. Among them were 1.5 million Soviet soldiers who had been POWs in Nazi concentration camps during World War II. On repatriation, if they were lucky and not executed, they were tossed into the Gulag as “spies and traitors.” More than 200,000 Christian clergy were murdered during communism’s 70-year reign by crucifixion, scalping, and, as the Commission on the Rehabilitation of Prisoners phrased it, “beastly torture.” “Clergymen were crucified on the churches’ holy gates, shot, strangled, doused in water in winter until they froze to death,” said Mr. Yakovlev.

His faith in human nature must have been severely shaken as he and his commission associates reviewed the dossiers of Stalin’s victims before sending them on to the Russian Supreme Court, which was expected to reverse the original guilty verdicts. Mr. Yakovlev told the London Times: “Most of the names were obviously political figures who were tried, sentenced to death and shot in the various blocks of repression like Trotsky, Bukharin, and so on. But sometimes a name would crop up that was completely out of context and we would have to search why they had been killed.”

In one case, the victim was the neighbor of the secretary to Lazar Kaganovich, one of Stalin’s henchmen. The secretary typed out the daily death list, and she added her neighbor’s name to secure the flat when it was abruptly vacated. Such behavior was not unusual. Arkady Vaksberg, the biographer of Andre Vishinsky, Stalin’s notorious prosecutor during the infamous Moscow trials, found a document detailing his phone call to a Kremlin bureaucrat asking for the transfer to Vishinsky of the dacha of a Soviet general he had just convicted of “treason” and who was to be shot that afternoon.

Mr. Yakovlev is pressing the Russian government to erect a memorial to the victims of Soviet repression on Lubyanka Square in Moscow because “this horrible place is where the mechanism of Stalin’s evil deeds was launched.” But there is as much chance that such a memorial will be built as that V. I. Lenin’s tomb in Red Square will be demolished. It would be a supreme irony if the American campaign, supported by an act of Congress, to build a D.C. memorial to the victims of communism were to be successful and fail in Russia. But that is to be expected. The Russian government is swamped with former KGB agents, including President Vladimir Putin himself.

Will there be a sign of gratitude for the work that Mr. Yakovlev and his commission have accomplished in these 13 years? There will not be because the Russian government and popular opinion cannot or will not confront the 70 horrifying years of the Bolshevik Revolution. Some Russians even look back nostalgically at the Stalin years, refusing to acknowledge the crimes of the Soviet past.

Such a state of denial is not so different from that of the extant left-liberalism credo that, by some metaphysical twist, regards America’s victory in the Cold War as a defeat and the Cold War itself as an illegitimate American aggression against a land that might have developed into a socialist paradise had it not been for American “imperialism.”