Imagine 20 Britains. Imagine 100 Londons. Now you are beginning to get the idea about China, where more than a fifth of the human race resides. Now imagine that vast country’s economy growing more than four times faster than Britain’s—growing faster, in fact, than any economy in history. According to Goldman Sachs, China’s gross domestic product will overtake Britain’s this year. By 2041 it is likely to be the biggest economy in the world. That’s what an average annual growth rate of 9 percent can do: Your economy literally doubles in size every eight years.

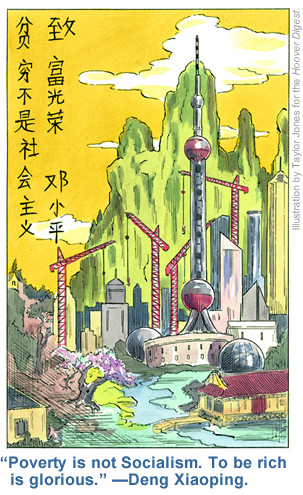

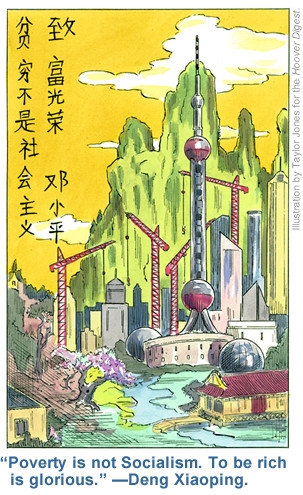

What does such extraordinary material dynamism look like? Having just visited five of China’s fastest-growing cities, I can report that it looks like the construction of London’s Docklands, projected onto multiple plasma screens, all running in fast-forward mode. I have never seen so many cranes. And they work day and night. Not even the United States in its most hectic years—the Roaring Twenties—can have been like this. You go to sleep not knowing how the skyline through your window will look the next morning. Forget the New World. This is the New, New World.

The change in China is so vast that it makes the lead stories in the Western media—the Labour Party conference, the appointment of a new chief justice in the United States—seem almost comically parochial. Did we really kid ourselves that 1989 marked the “end of history” and the “triumph of the West”? The biggest economic transformation of all time is currently being achieved by card-carrying Communists, who show no sign of relinquishing their monopoly on power. On the contrary; since taking over three years ago, President Hu Jintao has markedly tightened state control of the media.

The 60-billion renminbi question, of course, is how long the heirs of Mao can get away with running the ultimate contradiction in terms—”the socialist market economy.” Can you really present people, as consumers, with the seemingly boundless choice of the free market without offering them, as citizens, some political choice as well? Put differently, won’t the social strains arising from this second (and real) Great Leap Forward inevitably stimulate popular demands for democracy?

My hunch is that China’s economic and political fate will be decided by two key institutions. Both are networks. The first is the country’s financial system—the credit network that links the country’s vast private savings to its equally vast investment boom. The second is the global information network known as the Internet.

Let’s take the credit network first. This is the shadow side of the Chinese economic miracle. Sure, the People’s Republic has acquired a forest of high-rises, endless miles of new highways, and umpteen industrial estates the size of Wales. But its banks, stock market, and other financial institutions are a joke. The banks are relics of the old planned economy, owed unquantifiably large bad debts by the defunct state enterprises of Mao’s time. The relatively new stock market, meanwhile, is tiny in relation to the scale of the manufacturing sector. The result is that the allocation of funds for investment and credit is not done on the basis of meaningful competition and relevant information, but through personal connections that maximize returns to a powerful few, rather than general economic efficiency.

Will all the countless new tower blocks in Shanghai’s Pudong district be making money five years from now? I rather doubt it. What about the bizarre office building I saw in Shenyang that is actually the shape of a Chinese coin? Even less likely. Could the real estate bubble that currently dominates conversation in Shanghai and Beijing go pop? You bet. And what would the effects of such a property crash be on the economy as a whole? No one has the foggiest idea.

It may be that the familiar laws of economic development have been abolished by the Chinese Communist Party. It may be that China will be able to sustain this runaway growth without ever suffering a financial crisis of the sort that has periodically interrupted the miracles in other Asian economies. But I am doubtful.

The experts insist that there can’t be a Chinese financial crisis because the People’s Bank of China has accumulated such vast quantities of dollars in the past few years. But that is to exaggerate the importance of central bank reserves. China is certainly not going to suffer a currency crisis of the sort that hit Thailand and Malaysia in 1997; the pressure on the renminbi is upward, not downward, as speculators anticipate a further revaluation of the currency after July’s tiny move.

There are other kinds of financial crises, however. The United States had ample gold reserves in 1929—the biggest in the world. That did not prevent the banking panics that were the key drivers of the Great Depression. And let’s not forget the protectionist pressures building as China’s exporters erode ever more sectors of U.S. and E.U. manufacturing.

What would the political effect be of a recession in China? Again, nobody knows. But if there were any kind of public protest, I cannot believe it would be stamped out as easily as the democracy movement in the summer of 1989. One crucial change is that 100 million Chinese now have access to the Internet. It may be possible for the authorities to block the BBC’s websites, but so what? With the help of Google I was able to call up numerous articles on “corruption in China” from sources all over the world. There are simply too many Western news agencies—to say nothing of the countless personal blogs now out there—for censorship to be effective.

Another critical factor is the rising number of Chinese people who are learning English. I had not expected this, having rather believed the voguish line of a few years ago that our children would all have to learn Mandarin or perish. The reality is that in the major economic centers, English is ubiquitous. Street signs are in English as well as Chinese. Advertisements nearly all feature European models and at least one line of English. And young people are eager to try out their language skills. One keen freshman at Beijing University assumed I must be a visiting professor and asked if he could sit in on my classes. I had been on campus less than 30 minutes.

I suppose I came to China prepared for the old communist culture of evasiveness and stonewalling. I encountered the very opposite. People are keen to talk. They are not afraid the way people were in the pre-Gorbachev Soviet Union. If they are not pressing harder for political change, it is simply because they are too busy trying to make money. But if the money were to dry up—if the dodgy financial system were to crash before the worst of it has been flogged to gullible Western banks. . . .

If such an economic setback were to occur, people’s tolerance of the corruption that is inherent in the “planned market economy” might suddenly diminish. And with the Internet and the English language spreading so fast, there are ways to express disenchantment beyond the wildest dreams of the Tiananmen Square generation.

Watch this vast and vital space.