Who could have guessed when the presidential campaign began that the candidates would argue in their first debate over whether to announce an intention to kill terrorists in Pakistan or to “do what is necessary” without the announcement?

Yet there was Barack Obama, who opposed the surge in Iraq, where he promised a “responsible” withdrawal, vowing a surge in Afghanistan with targeted killings of Taliban and Al-Qaeda leaders in Pakistan. He defended his position on the grounds that the United States has the right to prevent attacks from Pakistan because that government is either unwilling or unable to do so itself.

Not long ago, Democratic candidates competed over who would get America out of Iraq fastest. The idea of committing the nation to victory in Afghanistan by taking the war into Pakistan seemed unthinkable. Antiwar Democrats must be in despair—except, of course, those who do not believe Obama meant what he said about Pakistan.

The United States has in fact been targeting terrorist leaders in Pakistan for years. Nonetheless, if the leaders of both major American parties genuinely agree on the propriety and need to attack terrorists in foreign states that are unwilling or unable to prevent attacks on Americans, that development is potentially of great importance.

The duty of a state to prevent domestic attacks from within its borders against foreign nationals, abroad or in international territory, has long been established. But, like many other international duties, it is rarely enforced. The Taliban government of Afghanistan gave Al-Qaeda a sanctuary in which to equip, train, and finance terrorist cells and orchestrate the many attacks it perpetrated. But the U.S. government failed to protect the American people from this obvious and ongoing threat until after the attacks of September 11, 2001.

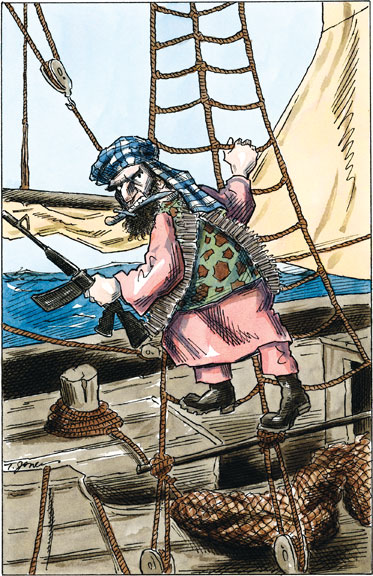

Since ancient times, states have frequently failed to police their nationals’ conduct effectively, thereby allowing (sometimes even encouraging or supporting) costly acts of terror, piracy, and other criminal conduct. Terrorist attacks orchestrated in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and other states have cost billions in damages and defense spending. The drama last fall off the coast of Somalia, in which pirates seized a ship loaded with tanks and held its crew hostage, was a flagrant example of how criminal activity runs riot when states cannot, or will not, use their police power to stop them.

It was not an isolated instance. In 2007, pirates seized almost four hundred ships in international commerce off the coasts of Somalia, Indonesia, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and the West Indies, among other places. Iranians send explosives into Iraq to kill Americans, Iraqi Kurds attack targets in Turkey, Colombian rebels have used Ecuador as a sanctuary from which to attack Colombia, Pakistani terrorists attack India, and Saudi princes, among others, fund violent activities in many places. No state can properly function with such activities going on within its borders, and no global economy or system of security can realize its potential unless such criminality is brought under control.

After September 11, 2001, the U.N. Security Council adopted resolutions instructing states to stop supporting terrorists within their territories and to prevent them from gaining the capacity for or conducting attacks. Treaties, almost universally adopted, had already prohibited support for airline and maritime terrorism, as well as hostage taking and drug trafficking.

But under international law, even when a state violates its duties by failing to prevent such conduct, other states are not permitted to enforce the rules. The Security Council must separately authorize enforcement of its resolutions, unless international law allows a rare exception to the general rule that states’ sovereign territory is inviolable.

This principle of inviolability came to the fore in the response of the Organization of American States (OAS) to Colombia’s attack last spring on FARC rebels who had been sheltering in Ecuador. Colombia raided FARC guerrilla camps in Ecuador without seeking Ecuador’s permission because it believed that Ecuador was supporting the rebels.

The raid was a success. Colombia announced that computers and discs seized in the assault proved that Ecuador and Venezuela had been supporting the rebels. Both Ecuador and Venezuela reacted with fury, moving troops and calling for a condemnation of Colombia by the OAS. Noting its charter’s absolute rule against any member violating the sovereign territory of another, the OAS declared Colombia’s action an unacceptable violation of international law. Whether Ecuador had violated international law was, in this context, considered irrelevant.

Even on the rare occasions when the Security Council authorizes the use of force, as it did in June 2008 to permit action against pirates within Somalia’s territorial waters, no effective response is assured. Pirates holding crews hostage have been able to ward off far more powerful naval forces. In 2007, pirates seized some twenty-five ships and were paid handsomely for each release. Everyone knows where the pirates are. The English-speaking spokesman of the pirates who seized the Ukrainian freighter Faina last fall remarked that although the pirates were surrounded by three warships, “what we are awaiting eagerly is the $20 million, nothing less, nothing more.”

Only time will tell whether the new U.S. president will act to prevent attacks from states that fail to perform their legal duty. The American people will wonder why we should be prepared to go into Pakistan, an ally that is at least attempting to stop the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, but not to stop weapons shipments into Iraq from Iran, an avowed enemy that is trying to kill U.S. troops and undermine security.

To be lawful and effective, such actions must be carefully designed and justified. But the fact that we have been unwilling to act, off Somalia and elsewhere, indicates not doubts about legality or legitimacy but a lack of resolve. And our failures to act in the face of blatant violations of international law are duly noted by both enemy and friend, resulting in costs potentially far higher than those that would be incurred by stamping out a group of pirates in a single, thorough operation.

Maybe the long presidential campaign forced the candidates to confront how our failure to enforce the international law obligations of states—to prevent attacks from within their borders—undermined our expensive efforts to succeed in Iraq and Afghanistan. One can only hope that the new president takes on the issue and does what is necessary, rather than merely claiming an intention to do so.