He could be generous, he could be irascible, but he could never be anything other than Glenn Campbell. During his long career, and from his retirement in 1989 until his recent death on November 24, no one else was ever described as being "like Glenn Campbell." He was an original.

It would be an understatement to call Glenn Campbell controversial and a virtual impossibility to keep track of all his battles, including those with more than one administration of Stanford University, on whose campus his Hoover Institution was and is located.

There was a Hoover Institution before Glenn Campbell became its director in 1960, but it was he who added world-class scholars to its huge library and massive archives, making it a think tank that would eventually be ranked number one among the think tanks of the world by the distinguished British magazine the Economist.

|

"It would be an understatement to call Glenn Campbell controversial." |

He also brought in the millions of dollars that supported their research and caused the institution to grow in size and in stature. But his achievement went even beyond that.

In an era when academic thinking was almost exclusively on the political left, the Hoover Institution became a refuge for top scholars who were out of step with that orientation, and who were therefore persona non grata at colleges and universities for which they were academically qualified but politically blackballed.

|

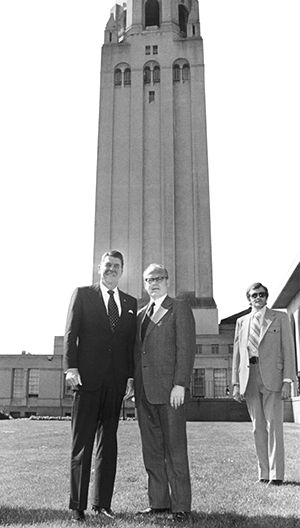

| Ronald Reagan and Glenn Campbell, March 1975.

|

While the media almost invariably referred to the Hoover Institution as "conservative" or "right-wing," a survey of its scholars during the 1980s found that there were slightly more Democrats than Republicans. In the surrounding Stanford University faculty—as with faculties at most universities—there were whole departments without a single Republican, at a time when the country was almost evenly split between the two parties.

Glenn Campbell liked to say that the Stanford faculty was leaning so far to the left that the upright scholars at the Hoover Institution seemed to be leaning far to the right.

While the Hoover scholars included such icons of free market economics as Milton Friedman, George Stigler, and Gary Becker—all Nobel Prize winners—they also included Nobel Prize–winning economist Kenneth Arrow, whose orientation was very different. These were all academically-based scholars who were affiliated with the Hoover Institution under one arrangement or another, spending varying amounts of time there. Other leading scholars were exclusively affiliated with the Hoover Institution and permanently in residence.

These included Peter Duignan and Lewis Gann, whose monumental histories of Africa were internationally recognized for their scholarship, but who were never on the faculties of any university. Given the benefits of being at the Hoover Institution—someone described it as having a MacArthur Foundation fellowship all the time—it was probably no great loss to them. But it was a huge loss to innumerable college and university students who would never hear anything that challenged the "politically correct" version of African history.

Another scholar in residence was the distinguished British historian Robert Conquest, whose monumental book, Harvest of Sorrow, spelled out the horrors of the man-made famine in the Ukraine which took millions of lives in the 1930s. While this famine was denied, not only by the Soviet government and its fellow travelers in the West, and downplayed or widely ignored by much of the intelligentsia, when the official Soviet files were finally opened under Gorbachev, it turned out that even more people had died than Conquest had estimated.

In short, the Hoover Institution was not only a refuge for scholars who refused to march in ideological lockstep with the fashions of the times, it was a refuge for ideas that were largely banished from academia and the media, but which could not be obliterated so long as they had a base from which inconvenient facts and analyses could be developed and published in books, articles, monographs, and op-ed columns.

It was Glenn Campbell’s contribution to America to preserve a genuine diversity that so many academics talked about but refused to permit on their campuses. That will be his enduring monument.