Education reform is no longer an issue of liberals versus conservatives. All sides of the educational policy debate now accept that the key determinant of school effectiveness is teachers—that effective teachers get good achievement results for all children, while ineffective teachers hurt all students, regardless of background.

Signs of this broad consensus abound. In Washington, the Obama administration’s Race to the Top program has rewarded states for making significant policy changes such as supporting charter schools. The Los Angeles Times has published the effectiveness rankings—and names—of six thousand teachers. And nationwide, the documentary Waiting for “Superman,” which strongly criticizes the public education system, has drawn avid audiences.

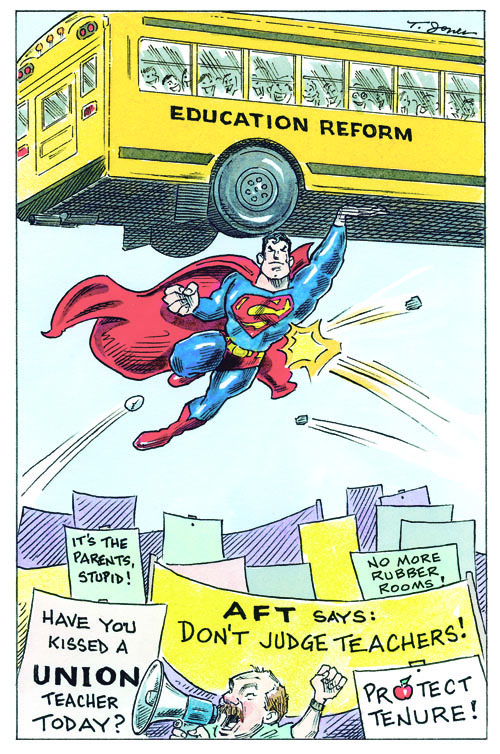

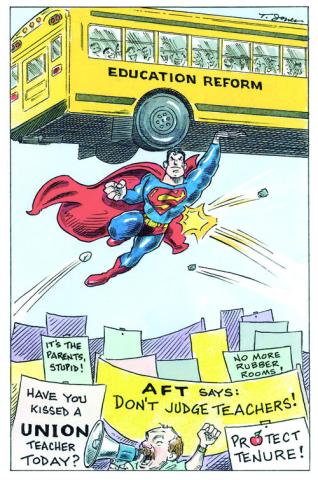

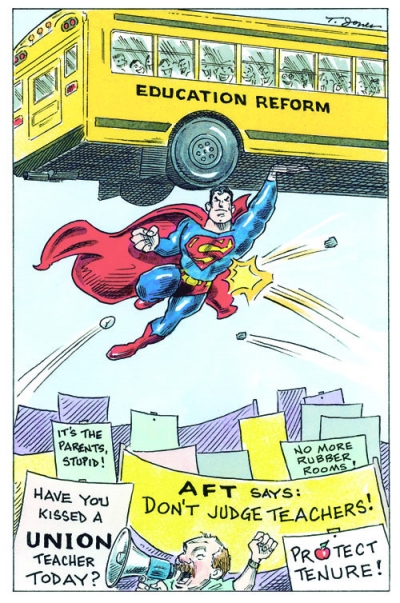

Also increasingly accepted is that the interests of teachers’ unions aren’t the same as the interests of children, or even of most teachers.

Until recently, the unions asserted that they spoke for teachers and that they should judge which reforms are good. Any proposal they didn’t like was labeled part of a “war on teachers.” Their first response to the Times’ reporting and to Waiting for “Superman” was to drag out that familiar line. According to the American Federation of Teachers, “The film’s central themes—that all public school teachers are bad, that all charter schools are good, and that teachers’ unions are to blame for failing schools—are incomplete and inaccurate, and they do a disservice to the millions of good teachers in our schools who work their hearts out every day.”

What’s really going on is different. President Obama states that we can’t tolerate bad teachers in classrooms, and he has promoted rewarding the most effective teachers so they stay in the classroom. The Los Angeles Times published data identifying both effective and ineffective teachers. And Waiting for “Superman” (in which I provide commentary) highlighted exceptional teachers and pointed out that teachers’ unions don’t focus enough on teacher quality.

This is not a war on teachers en masse. It is recognition of what every parent knows: some teachers are exceptional, but a small number are dreadful. And if that is the case, we should think of ways to solve the problem.

My research—which has focused on teacher quality as measured by what students learn with different teachers—indicates that a small proportion of teachers at the bottom are dragging down our schools. The typical teacher is both hardworking and effective. But if we could replace the bottom 5–10 percent with an average teacher—not even a superstar—we could dramatically improve student achievement. The United States could move from below average in international comparisons to near the top.

Teachers’ unions say they don’t want bad teachers in the classrooms, but then they act to defend them all, asserting that we can’t adequately judge teachers. Thus unions defend teachers in “rubber rooms”—where they are sent after being accused of improper behavior or found to be extraordinarily ineffective—on the grounds that due process requires such treatment. (In a perverse way, rubber rooms are good as long as it’s not feasible to remove teachers who are harming kids; it’s better to pay these teachers not to teach than to have more children suffer.)

So we are seeing not a war on teachers, but a war on the blunt and detrimental policies of teachers’ unions. If unions continue not to represent the vast numbers of highly effective teachers, but instead to lump them in with the ineffective teachers, they will continue doing a disservice to students, to most of their own members, and to the nation.

There is a place for an enlightened union that accepts the simple premise that teacher performance is an integral part of effecting reform. As the late Albert Shanker said in 1985, when he was president of the American Federation of Teachers: “Teachers must be viewed . . . as a group that acts on behalf of its clients and takes responsibility for the quality and performance of its own ranks.”

The bottom line is that focusing on effective teachers cannot be taken as a liberal or conservative position. It’s time for the unions to drop their polemics and stop propping up the bottom.