- History

- Military

- Contemporary

- US

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

As we watch a ferocious contest play out in the Republican primaries, it is worth looking back to 1952 to see how foreign policy affected that election. What I found has striking similarities to today: a president mired in public dissatisfaction; one political party with a wide open and bitterly contested primary, while the other has an arranged coronation of a seemingly unbeatable candidate; a reckless Republican ideologue complicating the party’s efforts to remake its image; a public weary of the burdens of shaping the international order, frustrated the president didn’t seem to have a strategy for winning the war, but anxious about the spread of a foreign ideology threatening the American way of life.

Even though it was the Democratic Party that could not coalesce around a single candidate, foreign policy was not a discriminator between its candidates. Then, as now, Democrats supported the continuation of the President’s foreign policy. Debate about America’s role in the world was argued in Republican ranks. While the 2016 field is, with the exception of Rand Paul, unanimous in their condemnation of President Obama’s policies, the 1952 Republican field was divided over how much to involve the United States in international politics. Isolationists carried the argument, but an internationalist carried the nomination—Eisenhower’s personal popularity decided the foreign policy direction of the country. And despite disagreements with Truman manufactured for the purpose of uniting Republicans, Eisenhower made the policies Democrats had begun bipartisan.

As the campaign for his successor heated up, Harry Truman had a 66% disapproval rating (a standard unsurpassed until George W. Bush at the depths of the Iraq War). Unusually for an American election, the economy wasn’t a major issue: The stalemated Korean War with its 25,000 Americans killed in action, fears over communist infiltration fanned by Senator McCarthy, and concerns about political corruption were the main motivating issues for the public.

Democrats were the party with a bitter primary contest in 1952, but candidates did not distinguish themselves on the basis of foreign policy, as they all basically supported the continuation of Truman’s policies. Party machinations to prevent anti-corruption campaigner Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee from securing the Democratic nomination only resulted in Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson being the party’s standard-bearer (after William Fulbright, Hubert Humphrey, Robert Kerr, and Averell Harriman dropped out of contention). Georgia Senator Richard Russell, Vice President Alben Barkley, and Massachusetts Governor Paul Deaver all refused to step aside, making for a messy convention.

The serious and important debate about America’s role in the world was conducted almost completely within the ranks of the GOP. Senator Robert Taft of Ohio led the conservative wing of the party, committed to abolishing the social welfare state established by the New Deal and letting the rest of the world take care of itself. New York Governor Thomas Dewey, the party’s standard-bearer of “Defeats Truman” fame from 1948, commanded Republicans accepting of the social welfare state and international interventionism to prevent the spread of Soviet communism.

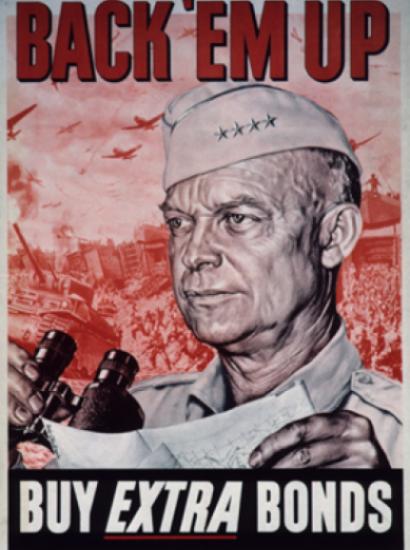

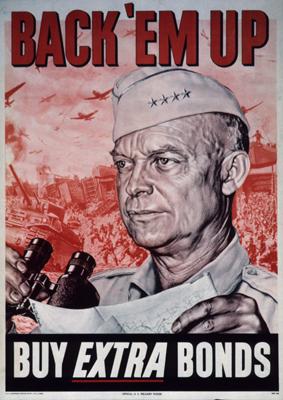

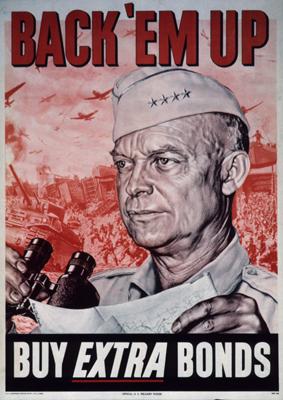

Conservatives within the party denounced the Dewey wing as willing to compromise their values. Dewey’s partisans fretted that purists would prevent Republicans from being electable at the national level. They sought an ameliorative figure as the party’s presidential candidate. Three candidates put themselves forward: Taft, California Governor Earl Warren, and former Minnesota Senator Harold Stassen. Republican operatives on the other hand yearned for someone widely admired but not considered a politician: General Dwight Eisenhower.

Dewey’s team staged a rally in Madison Square Garden, corralling 30,000 people cheering for Eisenhower, and had it filmed by aviator Jacqueline Cochran. Dewey organized a write-in campaign for Eisenhower in New Hampshire, and he carried the state. Eisenhower was reluctant to challenge Taft, but eventually, Taft’s strident commitment to isolationism brought Eisenhower into the race. On July 11th, Eisenhower declared, “I will lead this crusade,” and became a candidate.

The Republican convention was not without rancor: Eisenhower’s team accused Taft’s of stealing votes by packing state delegations with their supporters. A “fair play” motion unseated numerous Taft delegates and decided the convention in favor of Eisenhower, leading Taft supporter Everett Dirksen to denounce Republican liberals in his closing speech. By securing the nomination, Eisenhower decided the foreign policy debate in favor of an active internationalism.

Taft’s foreign policy more truly reflected the views of Republican primary voters, though. Even Eisenhower’s supporters admitted, “the American people took him for what they wanted Americans to be … I don’t think they really cared much about what he stood for.” He did not run a particularly high-minded campaign: He refused to denounce Eugene McCarthy—even had his picture taken shaking McCarthy’s hand—tried to throw Richard Nixon, his running mate, overboard when Democrats accused him of taking bribes (Nixon brilliantly saved his political career with the famous Checkers speech), and publicly denigrated Taft, describing him as “a very stupid man.”

While Truman tried to sustain bipartisan support for his foreign policies, Eisenhower orchestrated a tactically useful break to reunite the Republican party, accusing Truman of using the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Director of Central Intelligence as political props. Eisenhower made a grandstanding political gesture and said he would fly to Korea to bring that costly, inconclusive war to an end. He led in the polls throughout the campaign and 39 states—449 electoral votes to Stevenson’s 89.

Illustrating the resentment Democrats would have at a Republican candidate so easily stealing the national security mantle they had earned—by dropping the atomic bomb, consolidating the West in freedom, countering Soviet aggression, rebuilding western Europe and Japan, defending South Korea, building the Bretton Woods institutions, and bringing the state of Israel into being—President Truman wrote to Eisenhower congratulating him on his overwhelming victory, while also snidely adding, the presidential aircraft “will be at your disposal if you still desire to go to Korea.” (Harry S. Truman to Dwight David Eisenhower, 5 November 1952, 13 NATO 1412-13 notes).