“Americans May Be Losing Faith in Free Markets,” said the headline of a “news analysis” last summer by Los Angeles Times reporter Peter G. Gosselin. “Wave Goodbye to the Invisible Hand,” suggested an article by Washington Post columnist Steven Pearlstein. This recent theme in economic reporting actually began earlier last year with an article by New York Times economics reporter Peter S. Goodman. “A Fresh Look at the Apostle of Free Markets,” which I examined at length, was full of misinformation, not just about his subject, the late Hoover senior fellow Milton Friedman, but also about economic thought and the state of the U.S. economy.

Newer articles continue the trend. And they’re all wrong.

Many journalists claim that the U.S. economy since the late 1970s has been very free, with little regulation; that this absence of regulation has caused markets to fail; that there was a consensus in favor of little regulation; and that now this consensus is fading. On all these counts, the reports are false. Specifically, the U.S. economy has not been free since before the New Deal of the 1930s. Even before the 1930s, the U.S. economy was “mixed”—that is, a combination of economic freedom and government regulation—and Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal altered the mix substantially toward regulation and away from freedom. The deregulation of the late 1970s and 1980s reversed some of the regulations that came with the New Deal and some that preceded it, but the net amount of regulation has been much higher in the alleged era of deregulation than it was during the post–National Recovery Administration New Deal.

Moreover, most of the apparent “market failures” that these recent news articles refer to fall into one of two categories: either they are not market failures at all but market successes, or they are failures that are due to government regulation. Moreover, the consensus has not shifted from deregulation to regulation: there never was a consensus in favor of deregulation. Such a consensus prevailed among economists and a minority of politicians in the late 1970s and early 1980s but never among the majority of politicians. Finally, most of the problems that have happened in the U.S. economy in the past few years strengthen the case for economic freedom and against government control.

Consider some specifics. Pearlstein wrote:

For the past twenty-five years, the United States has put its faith in open, unregulated and lightly taxed markets, and there’s little doubt that over time, that model has expanded economic output and improved economic efficiency. But what Americans have also come to realize is that the same model is less adept at providing other things that we value highly—things like safety, fairness, economic security, and environmental sustainability.

There are two main problems with that two-sentence paragraph: the first sentence and the second sentence.

AN ERA OF DEREGULATION?

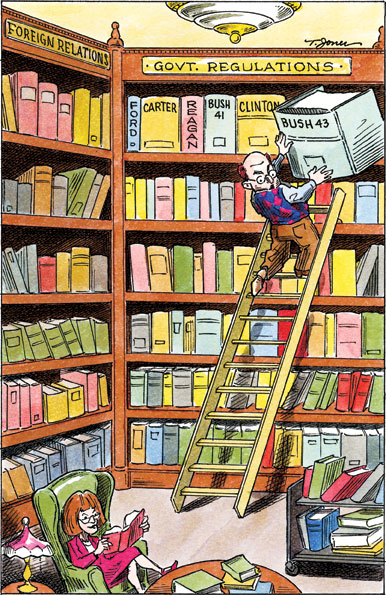

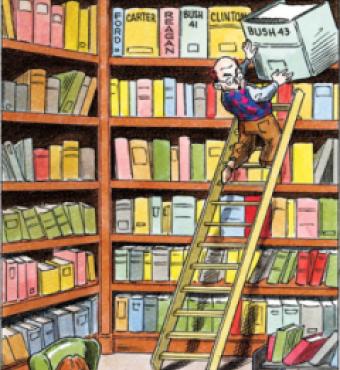

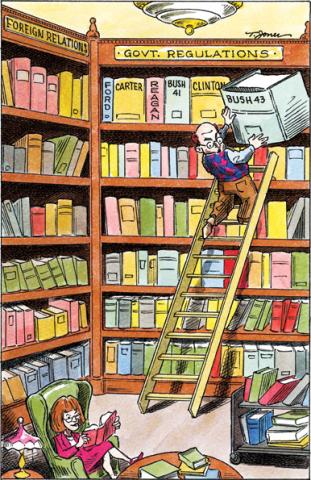

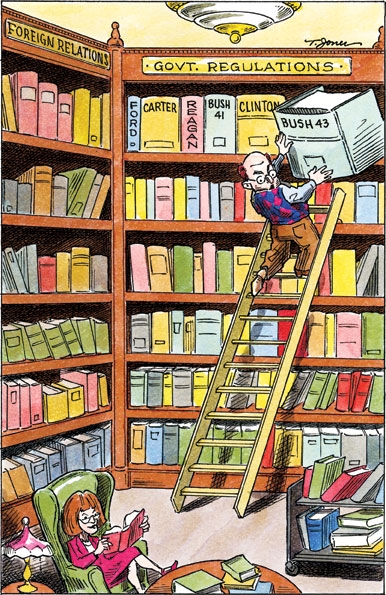

Take the first. “Unregulated markets” for the past twenty-five years? The Federal Register, which lists new regulations, averaged 72,844 pages annually during the Carter years of 1977–80. Presumably these were, by Pearlstein’s twenty-five-year standard, the last time before now that Americans failed to have “faith” in open, unregulated markets. Then the average fell to 54,335 during the Reagan years, rose to 59,527 during the Bush I years, to 71,590 during the Clinton years, and, finally, to a record 75,526 during the administration of that great believer in laissez-faire, George W. Bush. It’s true that when governments deregulate, they must announce those changes in the Federal Register, too, and so some of the pages represent genuine deregulation. But most of the pages were new regulations, no matter which president was in power at the time. So, far from moving away from regulation, the U.S. economy became even more regulated during Pearlstein’s alleged twenty-five-year era of light regulation.

The number of pages in the Federal Register is not the only measure we need consult. Veronique de Rugy and Melinda Warren, in Regulatory Agency Spending Reaches New Height, an August 2008 report by the Mercatus Center and the Weidenbaum Center, found that, between 1980 and 2007, roughly the years that Pearlstein labels unregulated, the number of full-time employees of U.S. government regulatory agencies increased 63 percent, from 146,139 to 238,351. During that same time, the U.S. population rose from 226.5 million to about 301 million, an increase of only 33 percent. Moreover, according to de Rugy and Warren, U.S. government spending on regulation alone (not including compliance costs, a much bigger number) tripled, from $13.5 billion to $40.8 billion (all in 2000 dollars). As a percent of GDP, spending on regulation rose from 0.26 percent to 0.35 percent, a 35 percent increase. Some deregulation.

One could argue that we need to distinguish between different kinds of regulation. Often people refer to “economic regulation” when they mean restrictions on new firms entering business or rules that require firms to get government permission before setting their prices. If this is what they mean, then there is a case to be made that, in substantial sectors of the economy, there is less government regulation now than before the late 1970s. There has been substantial deregulation at the federal level of airlines, trucking, railroads, oil, and natural gas, to name five large sectors. And indeed, as we shall see later, this deregulation has had, on net, good effects.

What was the nature of this new regulation? The biggest growth came in so-called homeland security, where spending more than quintupled, from $2.9 billion in 1980 to $16.6 billion in 2007 (all in real 2000 dollars). The second-largest growth rate was in regulation of finance and banking, where spending almost tripled, rising from $725 million to $2.07 billion. Together, regulation of homeland security and of finance and banking now accounts for more than half of federal regulatory spending.

Also incorrect is Pearlstein’s second sentence. Free markets have done much better than governments at providing safety, fairness, economic security, and environmental sustainability. The reason, for three out of the four, is simple. Economic freedom tends to lead to economic growth, as Pearlstein himself admitted in the above quote, and economic growth leads to more safety, more economic security, and more demand for environmental quality.

Safety and environmental quality are what economists call “normal goods.” As our real incomes rise, we want more of them. Over the twentieth century, as our real incomes rose, we workers demanded more safety, and we got it. As economist W. Kip Viscusi notes in “Job Safety,” published in The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, as U.S. per capita disposable income per year rose from $1,085 in 1933 to $3,376 in 1970 (all in 1970 prices), death rates on the job fell from 37 per 100,000 workers to 18 per 100,000. Note that all this preceded the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which originated in 1970. This shouldn’t be surprising: as workers, we show our demand for safety by the wage premium we insist on to take a given risk. As real incomes rose, this wage premium rose. Employers found it cheaper to avoid some of the risk premium by reducing risk—that is, by increasing safety. In short, there is and has been a “market for safety.”

The case with environmental quality is similar. Past some income level, environmental quality is almost certainly a normal good. But demand does not guarantee supply. Why not? One major factor is that so much of the environment is a commons, a resource that everyone can use but no one owns. As Garrett Hardin pointed out in his classic 1968 article “The Tragedy of the Commons,” when no one owns a resource, it will be overused because no one has much incentive not to overuse it. One obvious solution is to transform, to the extent possible, the commons into private property; this has been done with rivers, lakes, and land but is hard to do with air and oceans. But certainly we could go much further toward private ownership than we have until now, turning rivers, for example, into private property, as is done in Scotland. (Scotland, not coincidentally, has pristine rivers.) So, contra Pearlstein, one reason that we haven’t had the environmental quality we have demanded is that overregulation has prevented private ownership.

On the issue of economic security, the wealthier we are, the more secure we are. And because economic freedom creates wealth, as Pearlstein himself admitted, it necessarily creates security. Virtually no one in America ever needs to worry any more about starving. That is due in part to the welfare state but mainly to the riches created by relatively free markets. Of course, if by “economic security” Pearlstein meant confidence that one’s income will never fall, then he was right that markets don’t lead to that. Nor does government regulation. Government regulation of the economy’s money supply, high tariffs, high taxes, and regulations that kept wage rates high all caused the Great Depression or contributed to its length.

FREEDOM AND FAIRNESS

Pearlstein objected that economic freedom does not lead to fairness, but it does. One of the fairest things in life is that people reap what they sow, getting the benefits when they make good decisions and bearing the costs when they make bad ones. Markets create that fairness every day. Elsewhere in his article Pearlstein wrote that “government has had to step in to rescue the markets from their excesses and prevent a meltdown of the financial system.” If he really believes that those are excesses and if he truly wants fairness, why does he think that the government should bail people out from their mistakes? Some of the people whom the government is bailing out are very wealthy people who will retain more of that wealth because of the bailouts. Many of the people paying taxes for the bailouts are middleincome people who acted responsibly. Just what is Pearlstein’s view of fairness, anyway?

Gosselin, in his article, detailed three factors that he said were “pushing people to favor more regulation”—the high price of gasoline, the fall in house prices, and the dismal performance of the stock market for most of the current decade. If Gosselin were simply stating that these factors have made people more favorable to regulation, he might have a point. But that’s not all he said. He seemed to take the side of those who see these three factors as market failures. On gasoline prices, although he pointed out that most economists thought the then-high prices were due to “booming global demand meeting limited global supply,” he dismissed that reasoning, arguing that “the price run-ups seem out of whack with demand, which has increased only about 1 percent worldwide.” But Gosselin confused demand and consumption. Consumption of oil increased a little, whereas demand increased much more. That’s why the price rose. A standard exercise in introductory economics classes is to show students that when supply is fairly inelastic and demand increases a lot, the price will rise a lot and the actual amount produced and consumed will rise just a little. That is what happened in the world oil market.

Moreover, why has global oil supply been so limited? There are three main reasons, all entirely due to regulation. The first is OPEC, an organization of governments that regulates the supply of oil. OPEC was formed, incidentally, in response to President Eisenhower’s regulations on oil imports, which discriminated against imports from the countries that formed OPEC. The second is that almost all oil-producing countries have government-run oil industries. The third is the U.S. government’s restrictions on offshore drilling for oil and on oil development in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Whether one favors or opposes these restrictions on drilling, they do constrain the supply of oil and do, therefore, cause the price of oil to be higher than otherwise.

Interestingly, Gosselin leaves out the major price declines that have occurred in some of the most unregulated or newly deregulated parts of the economy: computing power (there is little regulation of the computer industry) and clothing (there has been a major shift toward free trade in clothing).

FANNIE, FREDDIE, AND THE HOUSING CRUNCH

On housing prices, Gosselin claims that “the rise in house prices and the recent plunge grew out of an almost unregulated corner of the mortgage market—the one for riskier loans.” But much of this problem arose, in fact, from regulation. Jeffrey Hummel and I detailed in an Investors’ Business Daily article last year how federal government regulation contributed to the problem.

First, the federal government helped create the boom in housing prices by helping to create moral hazard: people taking risks because they knew that if things turned out badly, someone else would bear some of the cost. The federal government’s semiautonomous mortgage agencies—Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae—all buy and resell mortgages. Of the more than $15 trillion in mortgages in existence in early 2008, about onethird were owned by, or securitized by, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Ginnie Mae, the Federal Housing Administration, Veterans Affairs, or other government agencies that subsidize mortgages. Although Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were no longer government agencies during the period at issue, they were government-sponsored enterprises. Many buyers of their repackaged loans, therefore, assumed an implicit federal government guarantee— an assumption, as we now know, that was all too true. This implicit guarantee caused less scrutiny by lenders than otherwise and thus helped drive up housing prices.

The federal government’s second contribution to the increase in housing prices was the Community Reinvestment Act. This act, passed in 1977 and beefed up in 1995, requires banks to lend in high-risk areas they would otherwise avoid. Banks that fail to comply pay fines and have more difficulty getting approval for mergers and branch expansions. As Stan Liebowitz, a University of Texas economist, has pointed out, a Fannie Mae Foundation report enthusiastically singled out one mortgage lender that followed “the most flexible underwriting criteria permitted.” That lender’s loans to low-income people had grown to $600 billion by 2003. Its name? Countrywide, the largest U.S. mortgage lender, now in deep trouble for its lax lending practices.

Finally, a little-noted change in regulations by the comptroller of the currency in December 2005 acted as the trigger. The comptroller made it mandatory for banks to require minimum payments on credit card balances. Many people who hold subprime mortgages would have trouble making a higher monthly payment on a credit card. Before this regulation took effect, many people’s priorities would have been mortgage first, credit card second; now, many borrowers have reversed the order. Thus, the comptroller’s seemingly small increase in regulation had the unintended effect of causing some mortgage borrowers to default.

This is not to say, of course, that private businesses never do anything stupid unless it is caused by bad government policy. Certainly, many actors in the private sector expose their money—and other people’s—to absurd risks. It is safe to say, though, that in the case of the subprime mess, regulation and government subsidies deserve much of the blame.

WHY REGULATION FAILS

Notably absent from all the articles discussed above is an argument for how regulation would work or how deregulation fails. I have already provided evidence of how badly regulation has worked in oil and in the housing market. Regulation generally works out badly for two reasons. First, regulators have little incentive to get things right. Indeed, when their regulations fail, they often use the fact to argue for more power and more regulation. (Astonishingly, the argument often works.) Second, regulatory agencies are often captured by the politically powerful and used to stamp out competition. Recent regulations on housing finance, for example, require mortgage brokers to be licensed. That will reduce competition in mortgage brokering and enhance the incomes of existing mortgage brokers.

Moreover, we have powerful evidence of the beneficial effects of deregulation. Airfares, for example, according to Brookings Institution economists Clifford Winston and Steven Morrison, are 22 percent lower than they would have been had regulation continued. Brookings economist Robert Crandall and Mercatus economist Jerry Ellig estimated in the late 1990s that when the lower air fares are adjusted for the decline in quality and amenities, passengers saved $19 billion a year. In other words, the majority of us prefer lower fares to higher fares, more meals, and emptier airplanes. According to Hoover economist and senior fellow Thomas G. Moore, inflation-adjusted rates for truckload-size shipments between 1977, the year before deregulation of trucking began, and 1982 fell 25 percent even as service quality improved. And, of course, because of decontrol of oil and gasoline prices under Presidents Carter and Reagan, increases in world oil prices have been passed on to consumers rather than suppressed, so that the time-killing lines for gasoline in the 1970s have not been repeated.

Perhaps I’m being too harsh on Gosselin. Maybe his tone simply reflected that of the Americans whom he sees as souring on economic freedom. But shouldn’t economic journalists get the facts right? And the three overriding facts are: we have not had a period of light regulation, deregulation did not fail, and regulation makes things worse.