- Education

- K-12

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

Five years ago, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) issued an alarming report called Reading at Risk, which declared that literary reading was in dramatic decline. The NEA reported a sharp drop from 1982 to 2002 in the proportion of people who were reading any kind of literature. Fewer than half of adults, the NEA said, had read any single work of literature during 2003, the previous year. Dana Gioia, then the chairman of the NEA, called the decline of literary reading a national crisis that represented a “general collapse in advanced literacy.”

Early this year, however, the NEA reversed course. It said the latest figures showed a turnaround: for the first time since 1982, the proportion of adults who had read at least one novel, short story, poem, or play in the previous year had risen.

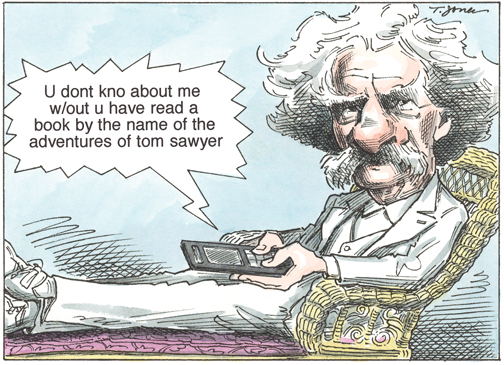

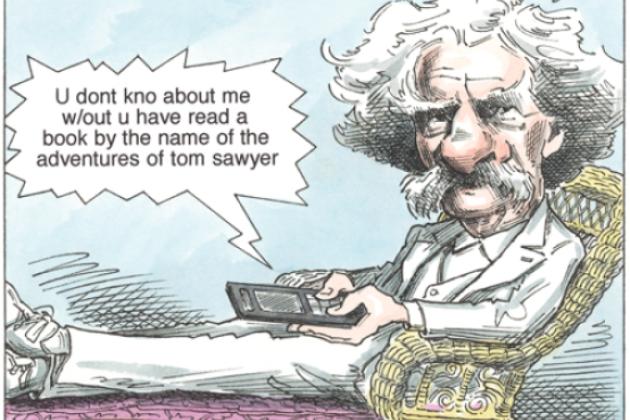

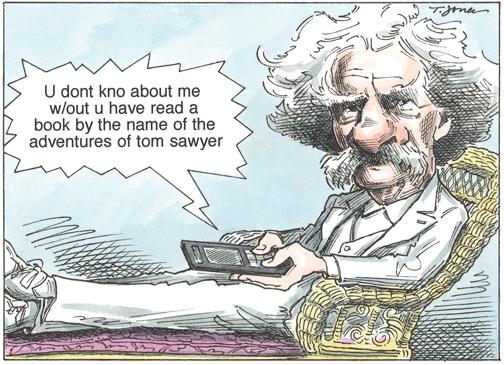

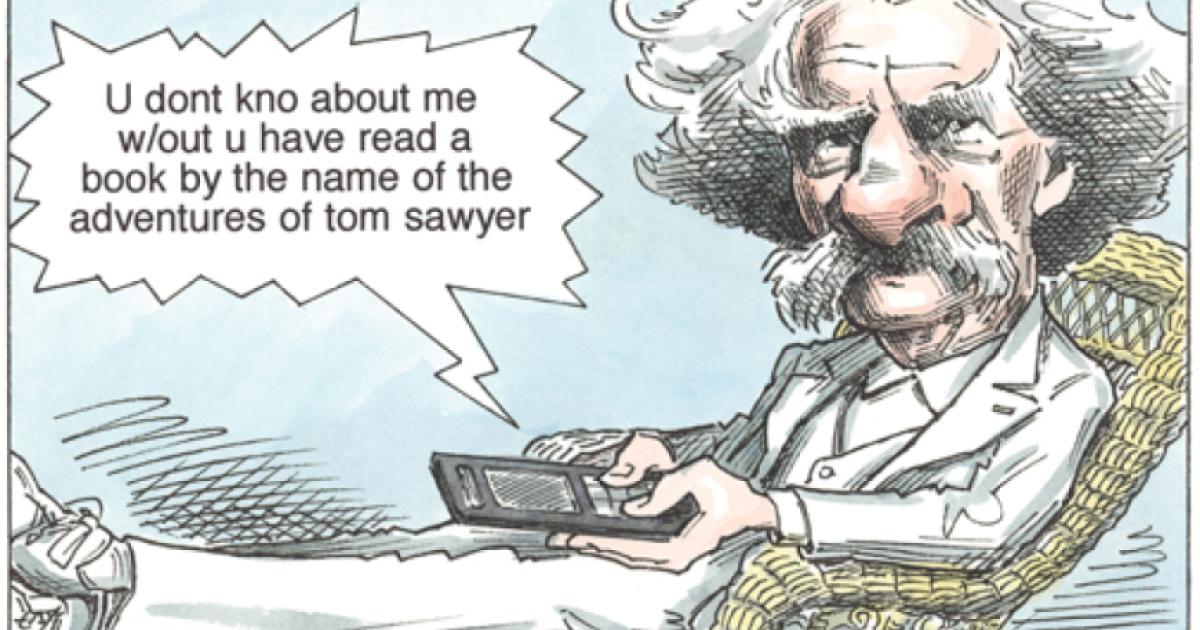

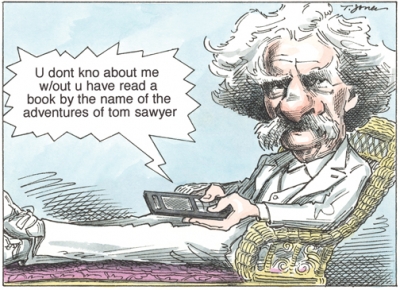

The number was still lower than it had been in 1982 or 1992, but Gioia concluded that the downward spiral seemed to have ended. He attributed the happy reversal to an NEA program called The Big Read, which encourages entire communities to read and discuss one particular book, such as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby, Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer, or Henry James’s Washington Square.

Not long ago, visiting a town in Wyoming where many people were reading the same book, I could see that The Big Read was a wonderful idea. Everyone was discussing the book. I thought wistfully of the many times I had argued with state education bureaucrats who staunchly opposed the idea of specifying a good book for students to read in any particular grade.

In these dark days for the publishing industry, which has suffered along with the rest of the economy, any good news is welcome. And yet it is hard to be cheerful when so many signs suggest that the increase in reading springs not from a newfound love of literature but from a devotion to trivial stuff online. Indeed, some critics of Reading at Risk contend that reading is not in trouble because young people are reading material on the Internet. Yes, but what are they reading? It is not likely to be Mark Twain or William Faulkner or Walt Whitman or Ralph Ellison, but rather Facebook, MySpace, or Twitter. Text messaging is also a form of reading, but it is not going to keep the higher end of literary culture alive.

There are other troubling signs of the decay of literary culture. The Washington Post has shut down Book World, its book review section. The New York Times Sunday Book Review is probably the last such freestanding section left among the nation’s newspapers (the Times eliminated its daily book reviews several years ago).

Few genuine outlets now exist for reviewing books, which is bad news for authors, many of whom work for years writing a book and getting it published but then get no reviews. Books that are not reviewed have a hard time finding an audience. The publication of the book is like a tree falling in the forest: If no one heard it, did it fall? If no one reviews a book, how will readers know that it exists?

The New York Times book section may also be at risk. It is no secret that the Times, struggling with a large debt, is cutting back sections of the newspaper. One recent week, the Sunday Book Review was a slender twentyfour pages and contained scant advertising. How long can it survive under such circumstances?

Even more ominous was the list emerging from “Ten Books to Read before You Die,” a feature that appeared on America Online not long ago. It grew out of a Harris poll that asked people to identify their favorite books. Aside from the Bible, the rest of the list reflected popular culture: The Lord of the Rings, surely on the list because of the wildly popular movies (I wonder how many of those who named this series had read any of them?), and the Harry Potter series, about which nothing more needs to be said (except that Harry Potter is seven books, not one). Add to those two by Dan Brown, including The Da Vinci Code (I would be willing to die with no regrets at all if I had never read that book); a book by Stephen King, a master of popular fiction; and Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, presumably because lots of people have seen the movie on television.

All that remains to round out the list of the books one must read before dying are Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged and two staples of the high school curriculum, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird and J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. One wishes that the Harris poll had asked people if they had read the book or merely watched the movie.

This list is the ultimate confirmation of the dumbing down of America. If these are the ten books one must read before dying, count me out. Why nothing by Mark Twain, whose novels, I believe, are certainly superior to anything on the Harris poll list? Why no mention of Shakespeare or Tolstoy? Why no George Eliot? Why no Ralph Ellison or Richard Wright?

Those writers, whose works can change the way you see the world, are not on the list because most Americans have never read them and because their writings have never been converted into a major computer-generated movie.

Why does it matter if America’s literary culture is dying? It matters because the ability to read challenging books helps make one more independent- minded. It encourages a way of thinking that is not a product of the mass media. It gives one the ability to think for oneself and entertain contrary opinions, and the freedom from dependence on Hollywood for a view of the world.

The literary culture is the last bastion of the individualist. Our society, our culture, even our economy depend on preserving free-thinking dissidents. And there is nothing that works better to free a mind from cant and superstition than to engage with the ideas of the world’s greatest writers.