- Contemporary

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- The Presidency

- History

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

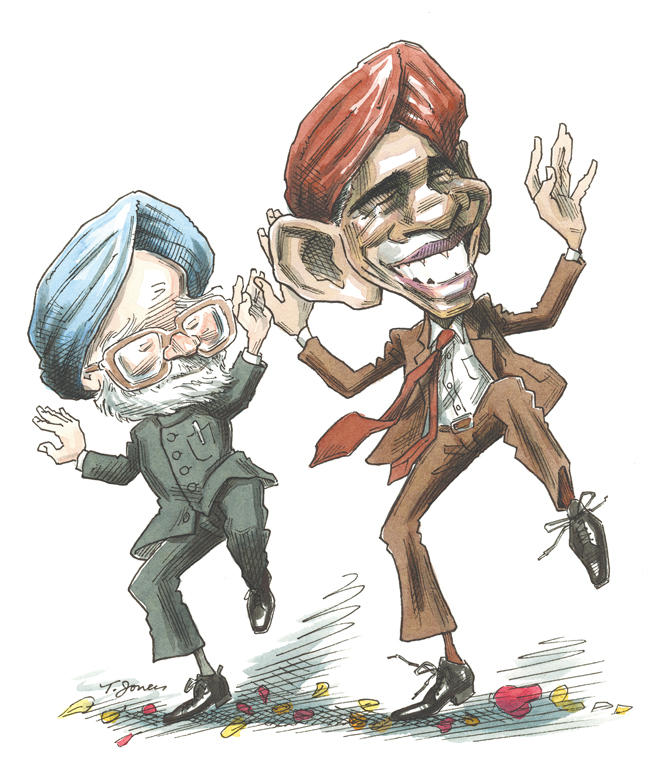

The world’s most consequential turbaned man, Manmohan Singh, glided through White House security a few months back as the honored dinner guest of Barack and Michelle Obama. Singh is the prime minister of India, a country that could, if President Obama shoots his diplomatic hoops right, come to be a pre-eminent American ally in the twenty-first century, taking its place alongside Britain, Israel, and, assuming the bolshie Yukio Hatoyama doesn’t live forever, Japan.

It doesn’t take a genius to recognize the political, strategic, and moral worth to America, the world’s most powerful democracy, of a strong alliance with India, the world’s largest. Obama, by no stretch a man of tepid intelligence, calibrated things artfully: not only was Singh the first state visitor to Washington since the president took office, but his trip was the first time that India had headed an American president’s list for a state visit—ever.

But until the state dinner, Obama had been indifferent to India. No doubt his mind was focused on other matters: the economy, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Iranian and North Korean nuclear shenanigans—not to mention health care reform. What was left of Obama’s attention was consumed by China, itself inseparable in so many ways from any resolution of America’s economic woes.

Given his workload, Obama has had scant inclination to pay much attention to, let alone court, Delhi. This has not gone down well in India, a country surrounded by a wall of thin skin. India had grown accustomed, under Obama’s predecessor, to alpha dog treatment. George W. Bush was the best American president India ever had, and Obama’s ability to take India for granted is, in some measure, a tribute to the extent to which Bush locked the two countries into a presumptively inseparable alliance. But for all his emphasis on diplomacy in dealing with hostile states, such as Iran, or inveterate competitor states, such as China, Obama has failed to grasp the diplomatic importance of tending to alliances, whether old and true ones, such as the one with Israel, or young and sensitive ones, such as the one with India.

India is not the India of Eisenhower’s time, or Nixon’s, or Carter’s, or Reagan’s. Sometime in the early 1990s, India finally acquired a “foreign policy” to replace the vexatious, preachy “postcolonial policy” that had previously guided its international relations. Equally, the United States, under Bush, finally acquired an “India policy,” as opposed to a “Pakistan policy” of which India was a mere by-product. In fact, under Bush, improved relations between the two democracies came to acquire an almost moral imperative, one that can—and must—survive the short-term reliance on Pakistan in the war against the Taliban in Afghanistan.

In any case, this is a war in which the United States has not, so far, been able to count on worthwhile Pakistani support. True, that country has taken pains to maintain the appearance of an ally, but every passing day brings new strains and new cynicism. Pakistan is “in,” meaning that it can use the war to its advantage in its messianic conflict with India. In addition, its overriding aim is to re-establish a Taliban regime in Kabul: how much plainer does its dissonance with American aims in Afghanistan have to be before Obama works out that his country’s long-term interests in the region lie with New Delhi, not Islamabad?

Finally, a broader word about India and its relationship with America: unlike China, which is inherently in competition for global leadership—and which will never accept American leadership or direction—India is a country that would, like Britain or Japan or Germany, settle for a partnership with the United States that guaranteed mutual benefit and respect. India’s natural state, if nations can be said to have such a thing, is neither triumphalist nor antagonist; it is cooperative and redemptive, much as America’s tends to be. One trusts that Obama will come to see these qualities as clearly as his predecessor did.