- Law & Policy

The law of search and seizure is not a topic that concerns most Americans in their daily lives. They do not commit crimes, and they have confidence that the police will not search them or their property without lawful authority. Criminal suspects, on the other hand, are very concerned about the lawfulness of searches and seizures when they face criminal charges. The search and seizure laws related to criminal activity are far too complicated, and they are continuously defined and redefined by state and federal courts.

A case pending in the Supreme Court of the United States will give that Court another opportunity to simplify what has become a complicated issue. The case, Heien v. North Carolina, was argued on October 6, 2014.

The facts of the case are unremarkable. Officer Matt Darisse, a twenty-year veteran of a county sheriff’s department, stopped Nicholas Heien’s vehicle as it was proceeding on a North Carolina highway with one of its two brake lights broken. Maynor Javier Vasquez was driving the vehicle, and Heien was sleeping in the back seat. Darisse issued Vasquez a warning ticket.

After another officer arrived at the scene, he and Darisse became suspicious of the car occupants’ behavior and asked Vasquez for permission to search the car. Vasquez replied that the officers would have to ask Heien, the car owner. Heien, much to his later regret, consented. The officers found cocaine in the car, and both occupants were charged with illegal drug trafficking. Vasquez pleaded guilty to a lesser offense. Heien filed a motion to suppress the evidence, claiming that the search was unconstitutional because the officers had no reasonable suspicion that a vehicle traffic offense had taken place, and thus, there was no basis to stop the car and conduct a search.

North Carolina law is ambiguous as to how many vehicle brake lights must work. Heien relied on a state law that said only one brake lamp on the rear of the vehicle was required. The State agreed with this interpretation. Heien claimed that Darisse’s belief that two brake lights must work was a mistake, and thus he was unreasonably stopped. The trial court denied Heien’s motion to suppress admission of the evidence, and he was convicted. The North Carolina Court of Appeals reversed, holding that state law only required one brake light. The North Carolina Supreme Court reversed the Court of Appeals. The North Carolina Supreme Court also ruled that Heien’s consent to the search was voluntary. The case then moved to the United States Supreme Court.

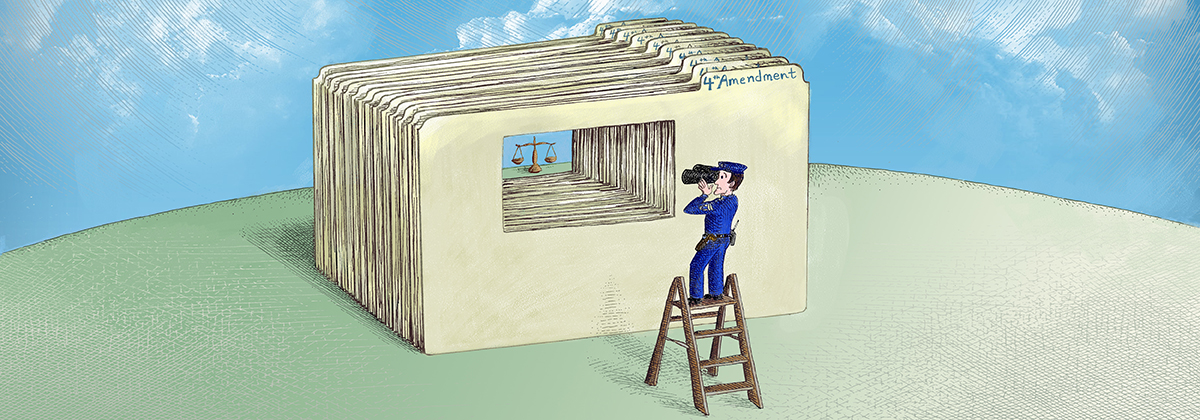

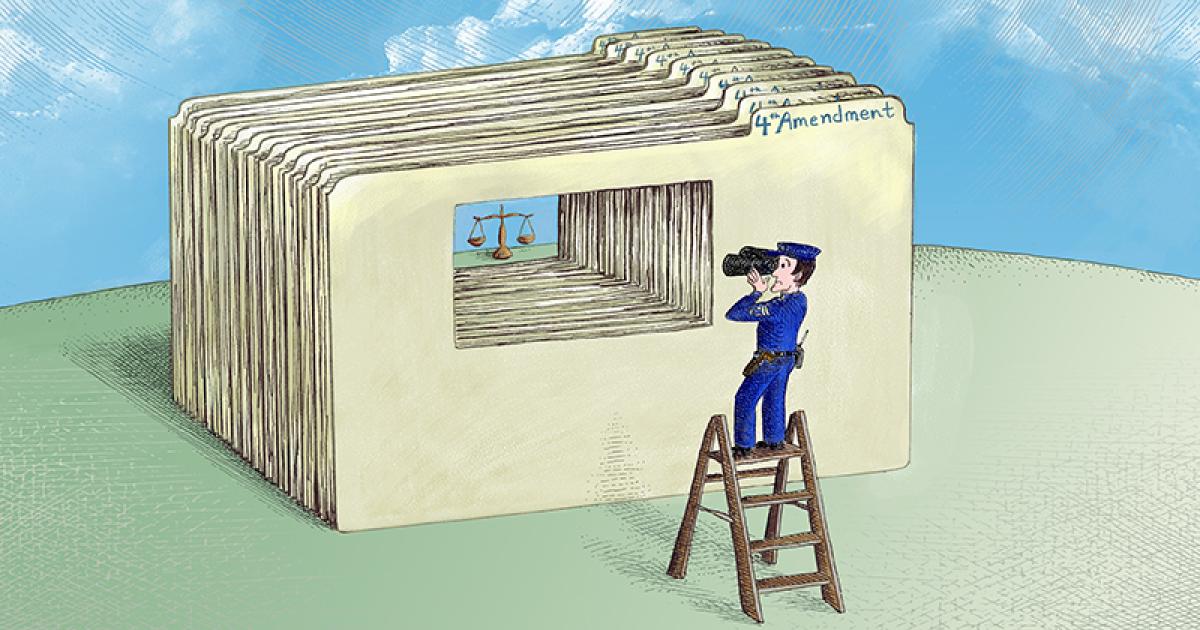

The question presented to the Supreme Court is: “Whether a law enforcement officer’s objectively reasonable mistake of law can support reasonable suspicion for an investigatory stop under the Fourth Amendment?”

The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution provides: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

The Fourth Amendment was applicable only to the federal government until the Supreme Court ruled in Mapp v. Ohio (1961) that it applied to the states under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Constitution is silent concerning violations of the Fourth Amendment. Specifically, the Constitution does not state that evidence obtained from an unreasonable search is inadmissible in court. To fill this gap, the Supreme Court created the “exclusionary rule” in Weeks v. United States (1914). The rule provides that evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment is not admissible against a defendant. The rule, which was designed to deter illegal police conduct, has been criticized because it hampers police investigations and results in allowing guilty criminals to escape conviction and punishment.

Through the years, courts have created exceptions to the exclusionary rule. An example is the “good faith” exception. Created by the Supreme Court in United States v. Leon (1984), it provides that evidence seized in good faith based on a warrant is admissible even though the warrant was found to be invalid. The Court found that imposing the exclusionary rule would not deter police misconduct inasmuch as there was no police misconduct.

A more recent example is Herring v. United States (2009). Police arrested Herring based on an outstanding warrant listed in a neighboring county’s database. A search incident to his arrest yielded illegal drugs and a gun. Within fifteen minutes, the police learned that the warrant had been recalled five months earlier, but the county’s database was never updated. Herring was prosecuted for being a felon in possession of a firearm and a controlled substance. The trial court assumed there was a Fourth Amendment violation, but held that the exclusionary rule did not apply. The federal circuit court of appeals affirmed, holding that the arresting officer was innocent of any wrongdoing and that the county’s failure to update the database was merely negligent.

In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court affirmed, holding that when police mistakes leading to an unlawful search are the result of negligence attenuated from the search, rather than systemic error or reckless disregard of constitutional requirements, the exclusionary rule does not apply. The Court said that the exclusionary rule is not a right, and that evidence should be suppressed only if it can be said that the law enforcement officer had knowledge, or may properly be charged with knowledge, that the search was unconstitutional.

The Court is increasingly finding, case-by-case, that the “judge-made” 100-year-old exclusionary rule is subject to reasonable exceptions.

The Fourth Amendment describes warrants, but not all searches require a warrant. There are many judge-made exceptions to the warrant requirement. The most obvious ones are a consent to search, a search incident to a lawful arrest, and reasonable searches associated with vehicle stops. It is settled law that vehicle stops based on a police officer’s reasonable mistake of fact are lawful. The Heine case hinges on an officer’s reasonable mistake of law concerning brake lights.

Heien argued that police officers are charged with the responsibility of knowing the law and that Darisse’s mistake regarding brake light law made the vehicle stop and subsequent search unlawful. North Carolina contended that there is no difference between mistakes of law and fact and that the stop and search were lawful.

The Supreme Court thus faces another jump ball question. Are mistakes of law different from mistakes of fact? A better question is, what difference does it make? The Fourth Amendment prohibits only “unreasonable searches and seizures.” The key word is “unreasonable.” Reasonable mistakes of fact or law should be treated the same. If the mistake in either instance was reasonable, the search should be lawful. If unreasonable, the search should be invalid and evidence seized barred from being used as evidence.

Officer Darisse was without doubt acting in good faith when he made the traffic stop. It is illogical to charge him with knowledge of all North Carolina traffic laws, especially when laws, such as the ones concerning the brake lights, are ambiguous. Such a conclusion should not shock the conscience or seriously raise the issue of privacy. The Supreme Court could emphasize the need for lower courts to give more deference to the word “unreasonable” in the Fourth Amendment. In essence, a search should be considered unreasonable only if the police acted in bad faith. By taking this approach, the Court could effectively bring an end to the exclusionary rule as it now exists and exceptions to the rule. A one-hundred-year-old judge-made law that functions to exclude evidence in order to punish the police is outdated.

Courts need only determine if a search was reasonable. Determining reasonableness is no more a daunting task than deciding guilt beyond a reasonable doubt or voluntariness of a confession. Simplification of search and seizure law would greatly benefit criminal courts, law enforcement authorities, and society.