“From this moment on, it’s going to be America First,” President Donald Trump proclaimed in his inaugural address. “Every decision on trade, on taxes, on immigration, on foreign affairs, will be made to benefit American workers and American families.” Although the new president did not delve into specifics in the address, he has made clear previously that “America First” policies will include tariffs, curbs on immigration, and reductions in overseas commitments, particularly those involving risk of military conflict.

Pundits and politicians of all stripes and nationalities characterized Trump’s foreign policy as a decisive and dangerous break with American tradition. Anne Applebaum decried Trump’s “utopian American nationalism, his ‘America First’ rhetoric and his brutal calls for protectionism and selfish tribalism,” warning that they portended the “steep and irreversible decline” of the United States. Der Spiegel asserted that Trump’s nationalism would destroy the “grand, binding values and goals” that have held the world together, leaving us with “a world in which each country is only looking out for itself.” Trump “does not see the use in unselfishly providing protection to allies, as the U.S. has done for decades with it soldiers stationed in Europe.” The Globe and Mail intoned, “If President Trump’s government vigorously pursues America First, it spells the end of the American Century, and the dawn of something darker.”

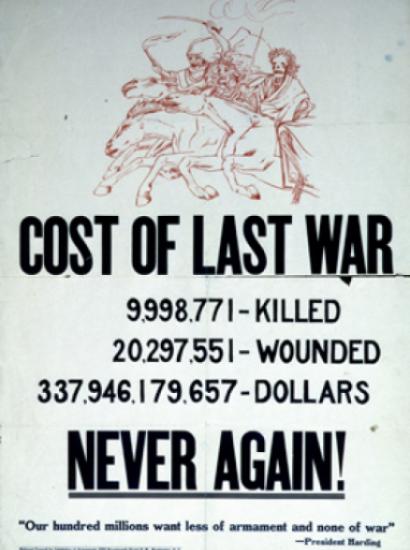

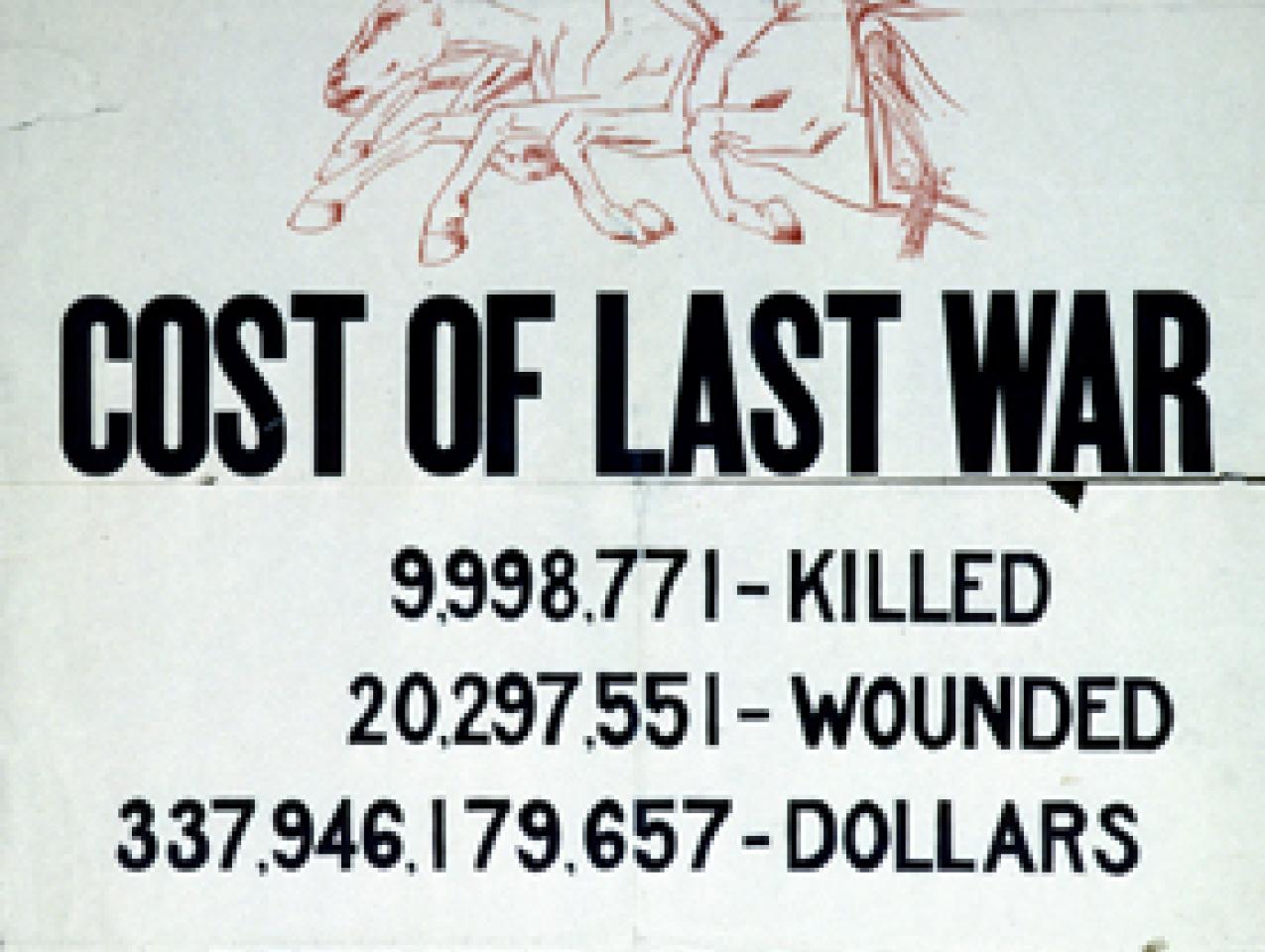

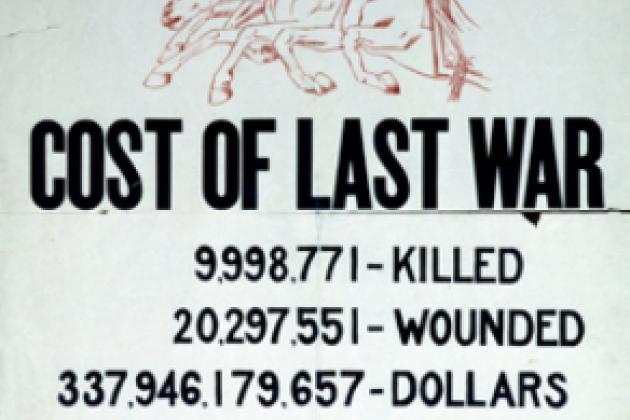

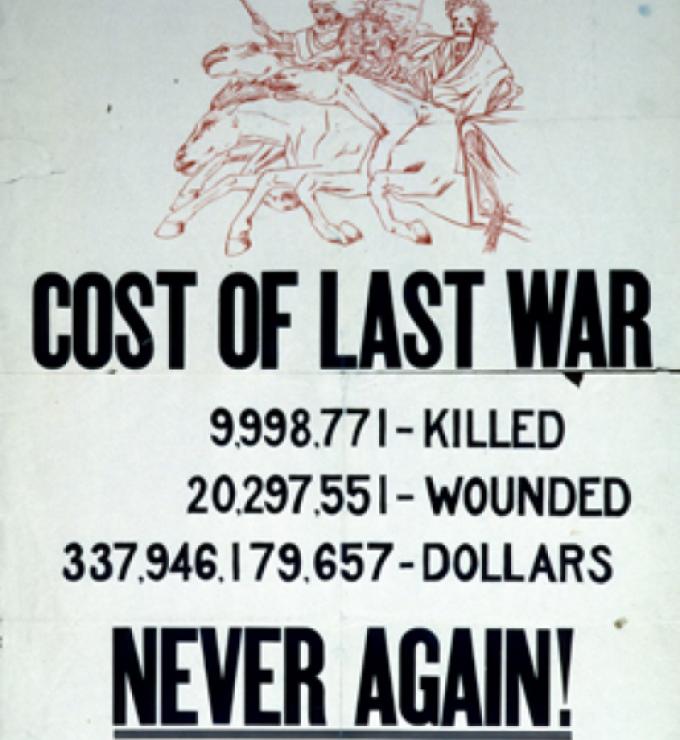

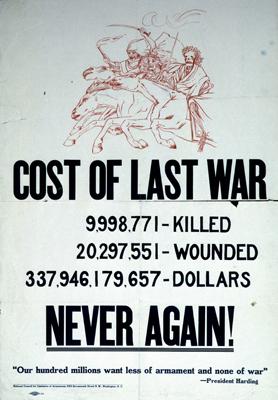

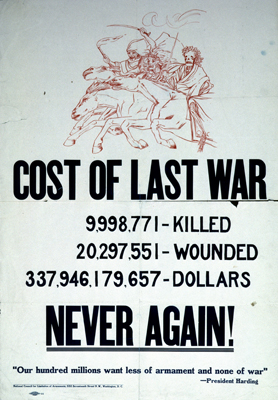

If one goes by presidential rhetoric, then Trump has indeed broken with tradition. No president in recent memory has begun his administration with open exhortations to put the nation’s interests first. More distant precedents, though, can be found. In 1921, Warren Harding warned in his inaugural address against free trade, foreign alliances, and world government. The United States, Harding averred, “can enter into no political commitments, nor assume any economic obligations which will subject our decisions to any other than our own authority.” Within the rhetoric of presidential elections, moreover, one can find numerous statements emphasizing the primacy of American interests. When George W. Bush was asked in an October 2000 debate to describe his foreign policy principles, he answered that his decision on any issue would be guided by the question, “Is it in our nation’s interests?”

If one moves beyond rhetoric to actual policy, the differences between Trump and his predecessors shrink much further. Nearly every President in U.S. history has put America’s interests first when crafting foreign policy. The United States has never protected its allies out of sheer altruism, but rather out of the belief that supporting those allies would help deter and, if necessary, defeat America’s adversaries. A few Presidents entered office believing that U.S. foreign policy need not serve U.S. interests, such as Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama, but they were quickly disabused of that notion by harsh international realities. In Carter’s case, the Iran hostage crisis and the invasion of Afghanistan did it; for Clinton, it was Somalia; for Obama, the disastrous Libyan intervention.

Restricting trade and immigration are hardly new policies; both have long enjoyed popularity across party lines. Wariness of military conflict likewise has deep roots—among conservatives as well as liberals. Doubts about the wisdom of entering World War I accounted for Harding’s aversion to international commitments, much as doubts about the Iraq War have instilled caution in Trump. During the 2000 election, George W. Bush’s warning against “nation building” reflected widespread disillusionment with Bill Clinton’s intervention in Somalia. Trump’s occasional statements that the U.S. military should be used solely to wipe out highly dangerous enemies echo the views of Andrew Jackson. Trump’s suspicions of alliances and international institutions were shared by most presidents prior to World War II, and are not very different from the “unilateralism” espoused early in the administration of George W. Bush.

Leading figures in the foreign policy establishment are predicting that Trump’s protectionism and disregard for alliances will cause a collapse of the global order. The world heard similar predictions when Reagan and George W. Bush took office—and yet the global order remained intact. In the case of Bush, it should be noted, problems created by the administration’s initial downplaying of diplomacy led eventually to greater interest in alliances and international cooperation. A similar progression is likely to occur under the Trump administration.

Much more damage to the international order occurred on the watch of the Obama administration. At the end of Obama’s eight years, the world was in a much less orderly condition than when he took office, thanks to ill-considered decisions such as the failure to honor America’s commitment to Ukrainian security, the hasty withdrawal from Iraq, the deposing of the Gadhafi regime, and the phony “red line” in Syria, to name a few. Given Trump’s assertiveness and his commitment to build up the military, Trump would have to fail spectacularly in the creation of policies to cause as much damage as Obama. If Trump does somehow end up on par with Obama, the world will probably weather the storm as well as it did in the past eight years.

It is conceivable that the Trump administration will take actions that disrupt the world in fundamental ways. So far, however, we have seen few indications that his ideas are going to turn the world upside down, and many indications that other nations are figuring out ways to ensure that Trump’s rocking of boats will not cause passengers to fall out. Trump’s cabinet appointments suggest that the crafting and execution of foreign policy will be left mainly to seasoned, pragmatic professionals. People have a knack for avoiding actions that are self-defeating.