- History

- Military

One hundred years ago this week doughboys of the American Expeditionary Forces went over the top in the Meuse River–Argonne Forest region of France, marking the beginning of what would become the bloodiest battle in American history. More than 1.2 million American soldiers took part in the six-week battle, part of a larger Allied effort known as the Hundred Days Offensive. By the time the battle concluded with an armistice on November 11, 1918, more than 26,000 U.S. soldiers—half of American combat fatalities in the Great War—would lie dead on the blood-soaked fields of France, with another 100,000 wounded-in-action.

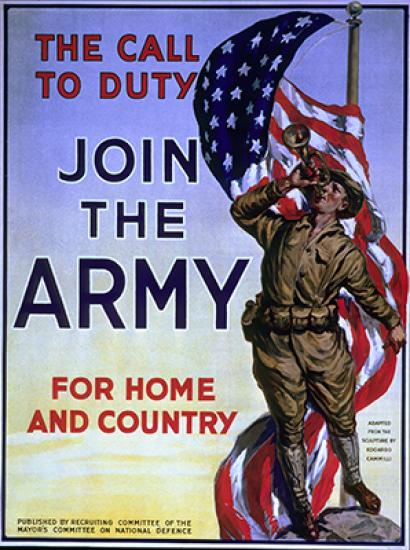

America was a late entrant into World War I. Its tiny pre-war military expanded in a period of less than two years to four million men, half of whom deployed to France to fight the Imperial German Army. Under the command of General John J. “Blackjack” Pershing, the American Expeditionary Forces were unevenly trained and for the most part untested in battle. But their arrival in France marked a definite turning point in the war, now in its fifth year. Pershing resisted the appeals of British and French leaders who had wanted to amalgamate U.S. forces into their formations rather than allow the American army a separate zone of operations. Now the time was at hand for Pershing and his divisions to prove their mettle in combat against a tough, battle-experienced, and determined enemy. The Americans would attack the German defenses guarding the key railroad junction of Sedan, a linchpin of the German railroad network on the Western Front.

The battle did not begin well for the Americans. Inexperienced troops led by untested commanders attacked into the teeth of German machine guns and failed to capture the high ground of Montfaucon, which dominated the battlefield. The cost in men and materiel was high; more ammunition was fired off on the first day of battle than was expended in the entire U.S. Civil War just a half-century earlier. The American transportation network became a snarled mess as commanders attempted to jam too many divisions along the few available roads. After a week the attack stalled and the First U.S. Army paused to unsnarl the mess.

After a period of reorganization the offensive resumed with fresh divisions in the van. The doughboys cleared the Argonne Forest by the middle of October. Due to the bloodbath the need for replacements was so great that Pershing broke up seven divisions to feed their troops into other formations. After another period of reorganization, the final attack began on November 1; a week later French and American forces seized Sedan. Along with affiliated French and British forces, the Americans had broken through the vaunted Hindenburg Line and shattered the Imperial German Army. It only remained for German apologists (including one Adolf Hitler) to peddle the nonsense that the German army had remained unbeaten in the field while being “stabbed in the back” with rebellion at home fomented by socialists, communists, and Jews.

Several legends were born in the fighting: Lt. Col. George S. Patton Jr. led a tank brigade in the attack and was wounded in combat, Captain Harry S. Truman’s artillery battery provided fire support for the infantry of the 35th Division, Sergeant Alvin York won a Medal of Honor while leading a small group of men in destroying a machine gun position and capturing 130 German soldiers, and the “Lost Battalion” held out against incredible odds in the Argonne Forest to enter the annals of U.S. military legends.

The U.S. Army also learned a great deal from the carnage in the Meuse River–Argonne Forest, its leaders (among them future U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall) determined to do better next time. They did. For all the shortcomings of the Army of the United States in World War II, its performance was indeed much improved from the bloody days of trench warfare during the fall of 1918.