- Security & Defense

- US Defense

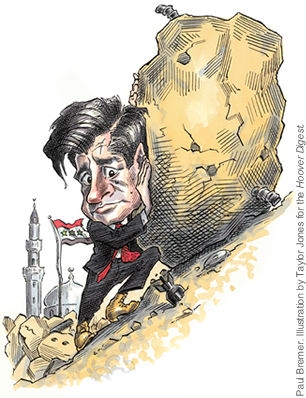

It is highly doubtful that a boulevard will ever be named or similar tribute paid to Ambassador L. Paul Bremer III, our civilian envoy to Iraq, assigned to direct its reconstruction and transition, if possible, to democracy. Whatever happens, Bremer is today by far the most important American in the Middle East, just as Douglas MacArthur was once the most important American in Asia. As it once was MacArthur’s task to transform a defeated Japan into a constitutional democracy without delegitimizing the emperor, it is Bremer’s task as Iraq’s civilian administrator to transform a defeated dictatorship into a secular democracy in a part of the world where American power is in inverse proportion to American popularity.

During the early years of the war in Vietnam, a neologism was born: to wham, an acronym for the phrase “winning the hearts and minds,” meaning trying to win all the Vietnamese, north and south, to welcome America’s participation in a war against a Communist takeover. And that will be Bremer’s task, whamming the people of Iraq to welcome Saddam Hussein’s defeat, achieved primarily by American might. For had it not been for President Bush, Saddam Hussein would still be around digging up new gravesites for Iraqi men, women, and even children. MacArthur was able to function without concern for hostile neighbors since most of Asia was delighted at Japan’s defeat. (China did not go Communist until 1949.)

No such luck for Paul Bremer. As Joshua Muravchik wrote in the Weekly Standard: “Never has the United States confronted so much hostility and distrust.” He cited Gallup polls in Muslim countries a few months after September 11, 2001, well before the second Iraq war, which showed abysmally low figures favoring the United States. In Turkey, a longtime ally of the United States, the “very unfavorable” anti-American camp dwarfed the “very favorable” vote by a whopping 67 percent to 3 percent. And it is the United States, not the perpetrators, which is being blamed (it goes with the territory) for the three terrorist acts in a defeated Iraq—the bombing of the Jordanian embassy, the bombing of the United Nations headquarters in Baghdad, and the truck-bombing/assassination of Ayatollah Mohammed Baqir al-Hakim at the Shia Imam Ali shrine in Najaf.

We cannot afford to let Bremer fail in his assigned mission because, in the words of New Yorker editor David Remnick, “[No] amount of military capacity or precision will get around the fact that an American presence in Baghdad will carry with it risks and responsibilities that will shape the future of the United States in the world. How the world comes to see this invasion . . . will be determined by the character of its aftermath.”

It used to be said that the job of NATO was to keep the Americans in, the Russians out, and the Germans down. Bremer’s job in the Middle East for at least the next five years is to keep America in, Iran out, and the Baath Party down. This time, however, the terrorists are under Iran’s control, and the Tehran theocrats will do everything in their power to prevent an Iraqi democracy from flourishing on Iran’s border.

As Bremer told an ABC News interviewer in June: “We have seen a rather steady increase in Iranian activity here, which is troubling. What you see at the most benign end of it is Iranian efforts to sort of repeat the formula which was used by Hezbollah in Lebanon, [that] is to send in people who are effectively guerrillas and have them get in the country and try to set up social services and decide that these social services are their ticket to popularity. And then they start to arm themselves and you wind up with a serious problem if you let it go too far.”

It will be Bremer’s job not to allow Iran to go too far. Can Bremer do the job or is he doomed to suffer the fate of Sisyphus, who in the land of the dead was forced for all eternity to roll up a steep hill a boulder that tumbled back down when he reached the top?

No Sisyphean fate overtook General Lucius Clay or General Douglas MacArthur. But Bremer starts with the cards seemingly stacked against him. So when he has a moment, I suggest he read Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power, by Niall Ferguson, the British historian and recently appointed Hoover senior fellow, who argues that the history of the British Empire has much to teach the United States.

Despite its many transgressions during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the British Empire left behind as its legacy a rule of law, a parliamentary system adopted by its former colonies, and an economic system that encouraged the unhindered movement of capital, goods, and labor. So what worked so well during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries might well be a model for the United States in the twenty-first century.